How does Jesus save?

Part Seven: The Final Scapegoat

ST 2007

How does Jesus save? Systematic theologians quibble and squabble over the Penal Substitution Theory (PST) of Atonement. Must I be saved from Satan or from God? Does God really love me, or was God simply paid off by vicarious sacrifice? What should I fear most, Satan or God’s wrath?

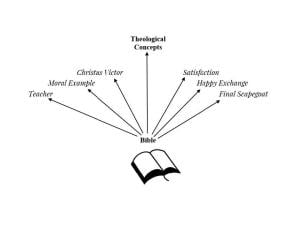

These questions have raised two problems. First, PST is still a theory about God’s grace. Second, PST is only one motif of six or more models for interpreting what Holy Scripture says about the atoning work of Jesus Christ. In the previous posts, we have mapped the terrain, so to speak.

When we began the long trek through this Patheos series on atonement, we posed the question: how does Jesus save? Along the path we have found in both Scripture and church history many different answers. These answers do not, by and large, send us in different directions. Rather, they provide various directional signs that lead in the same destination.

Here’s the list of atonement motifs—also called theories or models–we have been working with. [See Video: Models of Atonement]

- Jesus as teacher of true knowledge

- Jesus as moral influence

- Christus Victor

- Jesus as victorious champion

- Jesus as liberator

- Jesus as satisfaction

- Happy Exchange

- Jesus as the final scapegoat

In this post we’ll turn to Jesus-as-the-final-scapegoat. This is a new theory. Even though the theory is new, certainly the biblical basis is old. The final scapegoat motif interprets the family of originary symbols we’ve already identified: shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat. Jesus was never literally a shepherd or a sheep or a lamb or even a scapegoat. Metaphorically, he was all of these. Jesus was both like and unlike these members of the shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat family of metaphors. The public systematic theologian constructs rational models to draw out the implications of what the New Testament says.

In this post we’ll turn to Jesus-as-the-final-scapegoat. This is a new theory. Even though the theory is new, certainly the biblical basis is old. The final scapegoat motif interprets the family of originary symbols we’ve already identified: shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat. Jesus was never literally a shepherd or a sheep or a lamb or even a scapegoat. Metaphorically, he was all of these. Jesus was both like and unlike these members of the shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat family of metaphors. The public systematic theologian constructs rational models to draw out the implications of what the New Testament says.

The final scapegoat motif, like Jesus as teacher or example, is strongly revelatory. Recall, Jesus as teacher revealed something true about God or godliness. The revelation that takes place in Jesus-as-scapegoat, however, is a diaphanous perception about ourselves in our ungodliness. The death of Jesus reveals directly that we human beings are both liars and killers. Jesus-as-scapegoat reveals indirectly that God and God alone is gracious.

6. Jesus as the Final Scapegoat

“Jesus became the scapegoat to reveal the universal lie of scapegoating,” avers Richard Rohr. Now, what does this mean?

Perhaps you’ve noticed how in earlier posts we asked about coherence. It is important to the systematic theologian to ask: how does a specific atonement theory cohere with our understanding of the human condition? From what to we need salvation when we ask: how does Jesus save? Coherence is more important to the systematic theologian than it was for the biblical authors.

We are not asking for logic or coherence among the biblical symbols. One family of atonement symbols includes the good shepherd, lost sheep, sacrificial lamb, lamb of God, lamb upon the throne, scapegoat, and such. It would be fruitless to demand that these symbols cohere with one another. On the one hand, the good shepherd sacrifices his life for the sheep (John 10). On the other hand, it is the lamb who is slain (Revelation 5:12). Are these contradictory? No. They represent different imagery for the same atonement message. The systematic theologian does not look for logic or coherence here at the symbolic level of discourse. Rather, logic and coherence are treasures sought for at the level of rational reflection on the biblical symbols leading to an explanatory answer to our question: how does Jesus save? It is with this in mind that we turn to a specific strain within the family of shepherd ‘n’ sheep symbols, namely, the scapegoat.

Interpreting Scripture and Experience through Scapegoat Theory

Our hermeneutical method here will be to interpret both scripture and experience through the lens of scapegoat theory. The first thing we notice is that scapegoat theory is much more about the human condition—anthropology and hamartiology—than it is about things divine. The power of what happened in the cross on Good Friday is that a revelation occurs. We find out who we are. We find out that we are liars and killers. Our gracious God loves us, even though we are liars and killers.

This turns our previous discussions of blood sacrifice and divine appeasement into something much more dramatic than merely picking the right imagery for atonement. One thing that gets revealed in the cross is that our very reliance on sacrifice drives us away from the true God. It is not God who is appeased by sacrifice. Rather, those appeased by sacrifice are bloodthirsty killers. That’s us.

“Oh!” you might say. “I don’t have any inclination to murder someone. I’m a good person. Scapegoat atonement theory must be talking about someone else.”

I understand this reaction. I feel this way too. Yet, because we must deal with the lies we tell ourselves, scapegoat atonement theory just could be self-revealing.

Biblical Background: The Scapegoat Purifies Community

The sacrifice of the scapegoat purifies the community. More. It binds the community together into a state of purity. It is a historical fact that our very concept of atonement is associated with the scapegoat mechanism for purification.

In ancient Israel, the scapegoat bore the sins of Israel away on the Day of Atonement. Leviticus 16:16a, 21: “Thus he shall make atonement for the sanctuary, because of the uncleanness of the people of Israel….Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task.” By cursing the living goat and sending the cursed animal into the wilderness, the “uncleanness of the people of Israel” could be atoned for. Once the scapegoat was gone, then the remaining community could deem itself to be pure.

Does this atoning sacrifice rely on a mechanism for appeasing God? Mmmmm? Maybe not. Let’s consider an alternative interpretation. Anglican systematic theologian Katherine Sonderegger interprets Leviticus as a reiteration of Exodus. In Exodus, the God of grace calls Egypt’s slaves to freedom. How did freedom get into this picture?

The driving of the scapegoat out into the wilderness–most likely into the wilderness of Azazel–reminds Sonderegger of the years the Children of Israel spent in the wilderness before entering the promised land. The scapegoat is not a blood sacrifice. Rather, the scapegoat is preparation for receiving another dose of divine grace.

For this goat, driven out with sin on its head, set free to wander into the haunted desert: Do we not hear an echo of this exile in the liberation of Egypt’s slaves, driven out, led out into the wilderness by Cloud and by Fire, purified to serve the God of Israel in the wasteland across the Red Sea? Is there not a journey here, a movement that is the great movement of Scripture, from defilement to atonement, from bondage to freedom, from sin to release and redemption?” (Sonderegger, 2020, 2:394-395).

What Sonderegger avoids is the blood of sacrifice. Yet, she embraces the atoning efficacy of the scapegoat.

Would the Sonderegger interpretation fit all archaic societies? Or, only ancient Israel?

Israel was not the only archaic society to practice scapegoating. In Marseilles, an ancient Athenian colony, a human person rather than a goat performed the atoning task. Once the scapegoat—not literally a goat–was selected, he would be quartered and fed by the city-state for a year. When the ceremony began, the scapegoated person (pharmakos) would be dressed in sacred garments and decked with holy branches. He would be paraded through the streets of the city, where citizens would utter their curses in the form of prayers. “Prayers were uttered that all the evils of the people might fall on his head,” writes pioneer history of religions scholar James G. Frazer. “He was then cast out of the city or stoned to death by the people outside the walls” (Frazer 1890, 1935, VI: 253). The function of the scapegoat ritual is “the immediate and mediate expulsion of evil” (Frazer 1890, 1935, VI: 224). Even though Frazer believed this ritual to be an outdated superstition, he successfully described its elements.[1]

What we need to note is that, in the mind of the scapegoater, the goal was to rid the psyche or community of evil. Even if the scapegoat suffered, the communal motive was to serve the good by expelling evil. The ancient scapegoat ritual is alive and well today, even if it’s role in our psyches and our societies has become secularized and disguised. Belief in the sacrifice of the scapegoat for communal purification continues as a social mechanism right down to the present day in secularized and, hence, invisible form. The sacrificial mechanism helps the systematic theologian to define the fall into sin. That is to say, belief in the scapegoat mechanism manifests human sinfulness. Let’s turn now to scapegoat theory to shed light on what is ordinarily darkness.

René Girard’s Scapegoat Theory

We turn now to scapegoat theory. Specifically, the scapegoat theory we focus on is that of René Girard (1923-2015). Girard’s theory is carried on and expanded by scholars in COV&R (Colloquium on Violence and Religion). Here’s what we learn from scapegoat theory that become relevant to atonement theory for the systematic theologian.

The atonement ritual of ancient Israel maps our minds. In our minds we find meaning in self-justification, cursing, scapegoating, and perhaps even exacting violence against outsiders. And against alien insiders as well. We in the human race fool ourselves into believing that the scapegoat mechanism functions to cleanse us, to rid us of the sins which the defeated scapegoat bears away into the wilderness. This belief is nothing short of a lie, a lie at the foundation of much of what passes in our society as civic liturgy. Our default propensity is to delude ourselves by appealing to a pre-conscious confidence that this scapegoat mechanism justifies us and resolves evils.

René Girard helps make transparent what lies hidden behind our lies. The term scapegoat, Girard avers, “designates (1) the victim of the ritual described in Leviticus, (2) all the victims of similar rituals that exist in archaic societies and that are called rituals of expulsion, and finally (3) all the phenomena of non-ritualized collective transference that we observe or believe we observe around us….We cry ‘scapegoat’ to stigmatize all the phenomena of discrimination–political, ethnic, religious, social, racial, etc.–that we observe about us. We are right. We easily see now that scapegoats multiply wherever human groups seek to lock themselves into a given identity–communal, local, national, ideological, racial, religious, and so on” (Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightening 2001, 160). Like the prophets in ancient Israel, we need to cry “scapegoat!” so that lies might be exposed as lies, so that blind eyes can see again.

One Girardian insight is indispensable for theological anthropology and hamartiology. Here is that insight: social cohesion is founded on the successful execution of the scapegoat through sacrifice. “The purpose of the sacrifice is to restore harmony to the community, to reinforce the social fabric. Everything else derives from that” (Girard, Violence and the Sacred 1972, 8). Both our theologians and our political leaders yearn for peaceful human community. But, we must be cautious. When we bask within communal rapport we need to ask: is our communal harmony due to a victim of our scapegoating? The scapegoat ritual of ancient Israel has become a template for human community universally.

Patheos columnist Jack Hartjes reports that “This scapegoat mechanism has played an important role in human history. It singles out and shuns someone or some group who are not ‘WE’. It strengthens the sense of ‘US’. We become a more cohesive group, and we can forget whatever may have been dividing us and go out and do ‘great’ things.

If such a scapegoat mechanism is prevalent, we might find sacrifice propping up es sprit de court, team spirit, election campaign rallies, and nationalism. A delusion or self-deception is at work here. The scapegoat is sacrificed. But the sacrifice is justified on the grounds that the sacrifice purifies the community. Atonement, according to scapegoat theory, is a universal human proclivity made transparent in the symbolic practices displayed in Leviticus.[2]

Hamartiology: how do we sin?

Here is the hamartiology. The delusion within which you and I live is that we in our own communities buy into a lie that covers up an uncomfortable truth. What truth? Here it is: when engaged in scapegoating we only increase evil rather than rid ourselves of it. Scapegoating deforms the soul,

What!? Self-purification is a good thing, right? A society that gets rid of evil doers gets purified, right? So, how does it deform the soul? Here’s why. Because the soul forms itself around a lie, a lie that feeds and grows off violence perpetrated against those whom we victimize.

Here is the key lie: we tell ourselves that we are good and that aliens within or enemies without are evil. And, through this lie, we engage in self-purification. The lie might accomplish its task through gossip alone. But, the delusion can in some cases lead to the expulsion of the alien or the death of the enemy. Social harmony is built by scapegoating the foreigner, the alien, the enemy.

Up until this point we’ve been doing phenomenology. We’ve simply tried to make transparent the structure of human sociality.

Yet, this is the point where systematic theology contributes observations about human nature. Theologically speaking, there is no metaphysical mechanism that makes sacrifice efficacious. There is no deity just waiting for our propitiatory sacrifice. There is no ontological warrant for believing that a scapegoat can actually purify a community.

God identifies with the victim of sacrifice

Girardian theologian S. Mark Heim shines New Testament light into the darkness of self-delusion. “The mechanism of sacrifice is the way the powers of this world contain their own violence. But Jesus and the Gospel writers do not intend to endorse or comply with that mechanism” (Heim 9/2006, 22). The bad news of the gospel, says the systematic theologian, is that God identifies with the scapegoat — with the victim — not those in the community for whom the scapegoat allegedly atones. If Jesus would have his way, there would be no more scapegoats. Jesus’ death on the cross should be considered the last scapegoat, the final scapegoat. In Girard’s own words, “the Gospels shout from the rooftops that Jesus and all victims of the same type are innocent” (Girard, When These Things Begin 2014, 77). Impurity, in the final analysis, belongs not to the scapegoat but rather to the community who victimizes the scapegoat.

Girard’s scapegoat theory can be used to critique the unity of the Christian community. The Christian church frequently finds its unity by shunning a scapegoat. In recent times, gay and lesbian people have been sent out of the ecclesial community, complains Patheos columnist Matthew Distefano. “Many within mainstream Western Christianity believe the LGBT community…is to blame for the imminent judgment on America.” Disgruntled Progressive Scot English also complains. “Conservative evangelicals act like bigots towards those within the LGBT+ community.” Typically, bigots scapegoat through shunning and excluding. When Christians sacrifice a scapegoat, this signifies they have not incarnated the gospel message: no more scapegoats!

“We do not idealize sacrifice!” trumpets Sonderegger rightly (Sonderegger, 2020, 2:406).

Emory theologian Thee Smith wants to rescue our faith from sacred violence. If Jesus is in fact the final scapegoat, then we ask: how can Christian rescue faith from perpetuating sacred violence?

Perhaps the symbolic answer is found in the Eucharist. The symbolic genius of the Eucharist is that today’s Christian worshippers remember the victim, not the victor, of the crucifixion. The mass makes present to us today the body and blood of the one sacrificed, not the sacrifice (at least in non-Roman Catholic worship). The Sacrament of the Altar invalidates all other gestures of sacrifice we may offer.

Theology of the Cross

Girard’s scapegoat theory contributes to the Christian interpretation of the cross. Martin Luther gives us what we’ve come to call the Theology of the Cross.

“When God makes alive, God does it by killing; when God justifies, God does it by making human beings guilty; when God exalts to heaven by bringing down to hell…God hides divine eternal goodness and mercy under eternal wrath, God’s righteousness under iniquity.” (Luther, The Bondage of the Will (1525) / The Annotated Luther, 6 Volumes 2016-2019, 178).

Contemporary theologian Caryn Riswold tells us that, “for Luther, it is the scandal of the cross that revealed the paradoxical nature of God. It is the event where we find life in death, birth in blood, freedom in bondage, and divine in human” (Riswold 2022, 30).

Luther’s Theology of the Cross makes two points. The first has to do with revelation: the God of power is revealed under its opposite, namely, under weakness. The second has to do with the communication of attributes (communicatio ideomatum): in the human Jesus the divine Logos experiences sin, suffering, and death. This second aspect of the Theology of the Cross is stressed in the work of Jürgen Moltmann: “the pain of the cross determines the inner life of the triune God from eternity to eternity” (Moltmann 1993, 160).

What might Girard add to the Theology of the Cross? An emphasis on God’s identification with the sacrificed one, with Jesus Christ.

Systematic theologians attuned to Girard should be reminded that atonement theory needs to reaffirm that God’s grace is not dependent upon the propitiation of a sacrificed scapegoat. “It is often said that we are forgiven our sins because of the cross. But the cross was not a condition of forgiveness, which is unconditional,” Jordan Carson extols (Carson 2010, 329). Grace Adolphsen Brame reiterates: “How we understand God and God’s unconditional love affects how we understand sacrifice….Surely God cannot even conceive of being paid for grace or playing games of substitution” (Brame 2005, 181).

Anglican theologian James Allison tells us that “Girard has made alive the work of the cross — how Jesus gave himself up to a typical human lynching so as to undo the world of violence and sacrifice forever” (Allison 9/5/2006, 30). The implication for modern social analysis is clear. “The danger of ‘wars and rumors of wars’ of whatever sort is that they give us cheap meaning to hold onto, a quick shot of identity, a false sense of belonging, of togetherness, of virtue, of innocence and so on. That cheap meaning is always derived by positioning oneself over against some ‘other’ considered to be wicked” (Allison 9/5/2006, 33). What today’s world situation calls for s a New Testament prophet to make clear to contemporary society that we live in a delusion of our own making. But, before we answer this prophetic call, Girard’s scapegoat theory needs a friendly amendment, namely, the distinction between the visible and the invisible scapegoat. But, that’s a topic for other blog posts.

How does Jesus save?

Now, we approach an answer for the question: how does Jesus save? René Girard helps here. According to Girard, what Jesus says and what happens to Jesus converge on a single message: no more scapegoats! Jesus says that the human race throughout history, beginning already with Cain’s murder of Abel, has sought to establish a peaceful and just social order on the bodies of the slain. Prophets and wise counselors are routinely persecuted, some even “murdered between the sanctuary and the altar” (Matt. 23:35). Jesus’ diatribes against broods of human vipers are revelations of a truth: human social structures are built to cover violence (Girard, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World 1978, 159-164). The word of God Jesus is delivering comes in the form of a revelation of hypocrisy and a command to stop the cycle of violence. “Turn the other [cheek],” says Jesus, and “love your enemies” (Matt. 5:39, 44). Do not repay evil for evil.

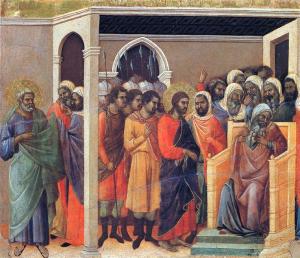

What Jesus says and what happens to Jesus make the same point. He becomes a scapegoat and is martyred. In order to prevent Jesus’ words from shedding the kind of light that would expose the truth, the dark powers of violence rise up to put Jesus to death (Schwager 1987, 191). Jesus is nailed to the cross as an act of legal justice in conjunction with mob violence.

Its single purpose: to maintain peace in the social order.

So, the chief priests and the Pharisees called a meeting of the council, and said, “What are we to do? This man is performing many signs. If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place and our nation.” But one of them, Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, said to them, “You know nothing at all! You do not understand that it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.” He did not say this on his own but being high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus was about to die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God. So, from that day on they planned to put him to death. (John 11:47-53)

What irony! To prevent the portending disruption of the social order by Roman reprisals, Jesus must be put to death so that “the whole nation” might not be “destroyed.” Also worthy of note is that after Jesus had been sent back and forth from Roman to Jewish tribunals: “That same day Herod and Pilate became friends” (Luke 23:12). The peace of the social arrangement is achieved and maintained through the death of the scapegoat.

The Truth Disclosed

What is revealed by the New Testament—and this is one reason the New Testament could be such an important document for the general public outside the church—is the cruelty of the scapegoat mechanism and the hypocrisy of a self-justified social order based on sacrifice. This is because the New Testament memorializes and celebrates the scapegoat victim, not the social order. Again, “The Gospels shout from the rooftops that Jesus and all victims of the same type are innocent.” (Girard, When These Things Begin 2014, 77). The written account is there for everyone to read. The scripture reading and resulting revelation help to unmask and thereby dismantle the scapegoat mechanism.

Again, S. Mark Heim, “No further earthly sacrifice is expected, accepted, or even possible” (S. M. Heim 2006, 158). Or, in the words of Girard, “God Himself reuses the scapegoat mechanism, at his own expense, in order to subvert it” (R. Girard 2014, 43). Once the truth has exposed the lie, it becomes clear that God’s will is that Jesus be the final scapegoat, that no more follow.

Sacrifice? Really?

A word about the word, sacrifice. It is copacetic to employ the term when describing Jesus’ disposition, Jesus’ willingness to give himself up to his enemies and be put to death despite his innocence. It is not copacetic, in my judgment, to use the term sacrifice to refer to some invisible metaphysical mechanism whereby the shedding of blood triggers a supranatural divine response that effects salvation. No such mechanism exists, even if many religious people believe in a mechanism of sacrifice. In fact, belief that such a sacrificial mechanism exists is a form of self-justification that makes victims in the form of scapegoats. “I used the word sacrifice to mean the giving of oneself even unto death,” writes Girard. “This is not at all what sacrifice means in archaic religions. In fact, it’s a complete reversal . . . Christians are right to use the word sacrifice for Christ” (Girard, When These Things Begin 2014, 115).

Recall our earlier discussions of the feminist critique of both Anselm’s Satisfaction Theory and the Penal Substitution Theory. When the biblical metaphors of suffering and sacrifice became literalized into an ideology, they became culturally dangerous. The example of Jesus’s voluntary sacrifice and suffering became a model by which a patriarchal class could demand sacrifice and suffering from its subjects, women in particular. Therefore, the announcement that no such sacrificial mechanism exists should come as liberation for some. What feminist theologians have bared is a tradition wherein the symbols of Jesus’ suffering and death were employed to scapegoat a dominated class. Ianna Jane Ray, author of The Atonement Muddle, capitalizes on the ambiguity of the biblical admonition to imitate Christ.

“When the suffering of Christ is used by a dominator who seeks to leverage an agenda of voluntary subjection to the dominator’s will, then it operates as an ideology to empower the oppression. But when identification with the suffering of Christ is sued by enslaved or abused people as entitlement to resist oppression, or by the sick as ability to endure the struggle of healing, then it can operate as a symbol of God’s empowering preference for the sufferer” (Ray 1997, 110).

When biblical symbols or atonement symbols are employed to justify scapegoating, they incarcerate rather than liberate. When an atonement theory fails to bring joy and peace, it’s time to exact a hermeneutic of suspicion.

Before departing from this topic, let’s compare for a moment. Treating Jesus as the final scapegoat has much in common with the first model, Jesus as the teacher of true knowledge. Yet, there is a difference. Rather than revealing a sublime path to God that spiritual disciples should follow, Jesus here reveals to us our sin and the hopelessness of justifying ourselves by scapegoating others. This theory also shares something with the Christus Victor and happy exchange models—namely, it shows that God has been willing to suffer as the victim of human scapegoating, and, further, once the truth has liberated us from the need for scapegoating we can appreciate the gracious offer of God’s justification.

Conclusion

As an exercise in systematic theology, we have compared and contrasted six complementary models of atonement. All of them originate in metaphorical families found in the Bible. Using the model method, we have explicated six theoretical answers to the question: how does Jesus save? Jesus-as-the-final-scapegoat is the theory we looked at in this post.

How do you like this theory? Is it better or worse than the others? Well, this certainly does not matter. At least if you’re Stephen D. Morrison. Why? Because, “thankfully, at the end of the day, we aren’t saved by theories. We’re saved by Jesus!”

Even if a theory cannot save us, it can be illuminating for faith seeking understanding.

To summarize, Girard’s theory of Jesus-as-the-final-scapegoat shares much in common with our first two models, Jesus-as-True-Teacher and Jesus-as-Moral-Influence. What happens in the cross, according to Girard, is a revelation. The revelation tells us that we human beings are liars and killers who rely on a non-existent mechanism of sacrifice.

Because God cannot be appeased by our sacrifice, we should become shocked by this revelation. Once shocked, we are ready to see the truth. The truth is that God is non-violent and gracious. God has always been non-violent and gracious. Our communion with God is due to divine grace and not to human sacrifice.

The implication for the controversy over Penal Substitution Theory should be obvious. PST is invalid if taken literally, because no mechanism of sacrifice exists. This should apply to Satisfaction Theory as well. Both PST and satisfaction are based on diaphanous biblical metaphors, to be sure; but we dare not treat them as literally describing a metaphysical mechanism. It is the responsibility of the systematic theologian to point this out.

The function of shepherd-sheep-lamb-scapegoat symbolism and the language of sacrifice in the New Testament is to make this point: no more scapegoats! (Peters, God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era 2015, 325-331). The high priestly office of Jesus Christ invalidates all other priestly sacrifices. It’s over. It’s done. God is no longer—if ever God was—in the business of accepting sacrifices. Stop it!

Finally, each of these six models has something to contribute to our understanding of the atoning work of Jesus Christ, the benefit of which is that sinners stand as justified before a forgiving God. The process by which an unjust person is rendered just is called justification, the topic of other Patheos posts.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching systematic theology and ethics. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] René Girard excoriates history of religions scholar, James Frazer, whom I cited above. “Frazer, along with his rationalist colleagues and disciples, was perpetually engaged in a ritualistic expulsion and consummation of religion itself, which he used as a scapegoat for all human thought. Frazer, like many another modern thinker, washed his hands of all the sordid acts perpetrated by religion and pronounced himself free of all taint of superstition. He was evidently unaware that this act of hand-washing has long been recognized as a purely intellectual, nonpolluting equivalent of some of the most ancient customs of mankind. His writing amounts to a fanatical and superstitious dismissal of all the fanaticism and superstition he had spent the better part of a lifetime studying” (Girard, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World 1978, 317-318). Frazer is so blind, complains Girard, that he is unable to see how he and his modern colleagues are actually practicing scapegoating while trying to explain it. Who is Frazer’s scapegoat? Religion itself, curiously enough. The takeaway message for us is this: we modern or postmodern thinkers will have to work diligently to remove the blindfolds from our eyes and open ourselves to a new level of self-understanding, even religious self-understanding. Scapegoat theory will aid us in this process, but only if we are willing to repent of our standard ways of thinking (Peters, Religious Sacrifice, Social Scapegoating, and Self-Justification 2018).[2] In her book, Evolution of Desire: A Life of Rene Girard, Cynthia L. Haven reports that the French literary critic had lived for a period in the American south. He came close to the lynching ritual, which would later influence his understanding of the mob spirit surrounding the scapegoat. Lynchings are not necessarily spontaneous events, Haven tells us. The lynching was a ritualized event with a predetermined outcome. Lynchings were sometimes planned in advance and advertised in newspapers. They drew large crowds of white families, like the guillotine executions of the French Revolution. Men were dressed up in their Sunday best for the celebration. Children played and and adults cheered as the drawn out savagery was displayed. The lynchers dismembered the victims while they still lived. Sometimes they doused the victim’s body with gasoline and set them afire. Grisly souvenirs were manufactured from the victim’s body parts and postcards were made from their body parts. Here is my observation. Such scapegoat rituals could take place only if the bonded community understood itself as morally self-justified. The American lynching must have reminded the young Girard of archaic scapegoating rituals.

Bibliography

Allison, James. 9/5/2006. “Violence Undone.” Christian Century 123:18 30.

Allison, James. 9/5/2006. “Violence Undone.” Christian Century 123:18 30.

Althaus, Paul. 1966. The Theology of Martin Luther. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Aulén, Gustaf. 1967. Christus Victor. New York: Macmillan.

Calvin, John. 1535. Institutes of the Christian Religion . Tr. Thomas Norton: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.toc.html.

Carson, Jordan. 2010. “The Suffering God and Cross in Open Theism.” Perspectives in Religious Studies 37:3 323-337.

Frazer, James. 1890, 1935. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, 12 Volumes. New York: Macmillan.

Girard, René. 2001. I See Satan Fall Like Lightening. Maryknoll NY: Orbis.

Girard, Rene. 2014. The ONe by Whom Scandal Comes. East Lansing MI: Michigan State University Press.

Girard, René. 1978. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

—. 1972. Violence and the Sacred. Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

—. 2014. When These Things Begin. East Lansing MI: Michigan State University Press.

Haven, Cynthia L. 2018. Evolution of Desire: A Life of Rene Girard. East Lansing MI: Michigan State University Press.

Heim, S Mark. 2006. Saved from Sacrifice: A Theology of the Cross. Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans.

Heim, S.M. 9/2006. “No More Scapegoates.” Christian Century 123:18 22-29.

Hultgren, Arland. 1987. Christ and His Benefits: Christology and Redemption in the New Testament. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Luther, Martin. 1955-1986. LW. Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 Volumes: St. Louis and Minneapolis: Concordia and Fortress.

—. 2016-2019. The Bondage of the Will (1525) / The Annotated Luther, 6 Volumes. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

—. 1883. WA. D. Martin Luthers Werke: Kritische Gesamtaufgabe 69 volumes: Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger.

Moltmann, Jürgen. 1993. The Trinity and the Kingdom. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Peters, Ted. 2018. “Religious Sacrifice, Social Scapegoating, and Self-Justification.” In Mimetic Theory and World Religions. Eds., Wolfgang Palaver and Richard Schenk. East Lansing MI: Michigan State University Press; 367-384.

Ray, Ianna Jane. 1997. “The Atonement Muddle.” Journal of Women and Religion, 15.

Riswold, Caryn. 2022. “Already Freed Christians Should Serve (Cake): Religious Freedom Claims and Christian Privilege.” Luther’s Teaching and Our Work for Freedom, Justice, and Peace. Eds., Alan G. Jorgenson and Kristen E. Kvam. Minneapolis MN: Fortress; 22-40.

Schwager, Raymund. 1987. Must There Be Scapegoats? Violence and Redemption in the Bible. New York: Harper.

Sonderegger, Katherine. 2015 and 2020. Systematic Theology. 2 Volumes. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Tanner, Kathryn. 2001. Jesus, Humanity, and the Trinity. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Westhelle, Vitor. 2022. “Usus Crucis: The Use and Abuse of the Cross and the Practice of Resurrection.” In Encountering Luther , by eds Kirsi Stjerna and Brooks Shramm. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.