The Wolves of Jack London

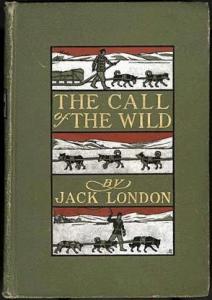

Jack London 1: The Call of the Wild

The Wolf in Dog’s Clothing [1]

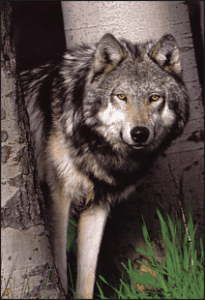

“Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves,” warns Jesus (Matthew 7:15). According to Jesus, “wolf” is a metaphor for false prophet. According to American novelist Jack London, “wolf” is a metaphor for the fallen human race. In one of the most widely read novels of all time, The Call of the Wild, along with sequels making up London’s Wolf Troika, White Fang and The Sea Wolf, London undresses the wolf hiding in human clothing. Literary lycanthropy, is one way to describe London’s genius.

The Plot

Just a quick reminder of the plot in The Call of the Wild. Buck, a pet dog from Santa Clara Valley in California, was dognapped and taken to Alaska to pull sleds. In the Klondike, away from civilization, Buck began to revert to an earlier stage of evolution. “The dominant primordial beast was strong in Buck,” writes London. After a fight with another dog, Spitz, Buck emerges triumphant over Spitz just as the wolf becomes triumphant over the dog. “Buck stood and looked on, the successful champion, the dominant primordial beast who had made his kill and found it good” (London, Call of the Wild).

What is true for the wolf within Buck is as true for the wolf within the human. The dog slaver gained dominance over Buck by hitting him with a club.

“After a particularly fierce blow he [Buck] crawled to his feet, too dazed to rush. He staggered limply about, the blood flowing from nose and mouth and ears, his beautiful coat sprayed and flecked with bloody slaver. The man advanced and deliberately dealt him a frightful blow on the nose. All the pain he had endured was as nothing compared with the exquisite agony of this” (London, Call of the Wild).

What Jack London himself witnessed in the Klondike that became background for his wolf books was human nature in the raw. When gold prospectors from California and the rest of the world converged on Alaska in the 1890s, they left their modern humanity behind. The civil became uncivil. The humane became inhuman. Law and order were discarded and replaced by the “Law of Club and Fang.” The primordial wolf, once suppressed, emerged again in both dog and human with ferocity and bloodshed. At any moment, London implied, what we know as orderly civilization could suddenly revert to an earlier stage of evolution where nature is blood “red in tooth and claw” (Tennyson, In Memoriam).

Devin Zuber observes that “London’s highly popular Call of the Wild was but one of many new kinds of writing about animals that burgeoned at the turn of the century as humans were reconsidering their place in the cosmos and the natural order of things” (Zuber, 2019, 102).

The Evolution of Sin?

Might there be a dovetail between Jack London’s evolutionary anthropology and the public theologian’s understanding of original sin? Was the masterful teller of dog stories actually a literary philosopher exploring human nature? Was London even conscious that he was synthesizing science with religion?

Here are our existential questions: are we Homo sapiens more civilized than a wolf pack? If not, can we hope for redemption descending from heaven in the form a UFO coming to Earth to advance our civilization beyond the wolf stage of evolution? Will extraterrestrial aliens provide the grace we need to transcend our inherited wolf traits?

What!? UFOs!? How do these things fit together?

Theology and Literature

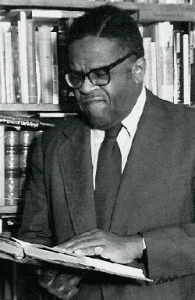

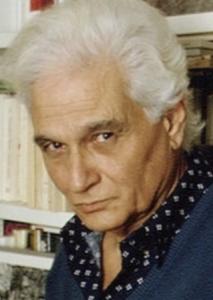

In this Patheos Public Theology causerie series analyzing a portion of the corpus of prodigious California novelist and short story author, Jack London, we will apply the analytic tools developed in the field of Theology and Literature, more frequently called, Literature and Religion. Specifically, we will follow the path blazed by one of my favorite University of Chicago professors, Nathan A. Scott (1925-2006).

I call this method theology-of-culture. It’s based on Paul Tillich who would examine literature or art for its depth. In its depth, the literary critic can discover what existential questions are being asked. What is meaningful? Can we find grace at the depth of our being?

We have only one topical question: will we Homo sapiens evolve into civilized creatures that outgrow our wolflike tendencies toward violence? We will ask this one question multiple times as we review Jack London’s different writings. Here’s what’s coming.

THE WOLVES OF JACK LONDON / Jack London Society

Jack London 1: The Call of the Wild

Jack London 4: Lone Wolf Ethics

Jack London 5: Wolf Pack Ethics

Jack London 6: Wolf and Lamb Ethics

Oh, yes, multiple movies have been made of The Call of the Wild over the decades. Most recently in 2020 (Hulu online), The Call of the Wild film starred Harrison Ford. Ford played a man named John Thornton, not Buck. In the 1935 film, it was Clark Gable (full movie online). And, in the 1997 version, it was Rutger Hauer as John Thornton and Richard Dreyfuss as narrator. You can watch a 2009 children’s variant with Christopher Lloyd here.

The field of Theology and Literature has fallen on rough times. More frequently today, universities offer courses on Theology and Film.

Theology, Science, and Literature

I was privileged to study under Nathan A. Scott at the University of Chicago. Dr. Scott was a pioneer in the field of Theology and Literature (Scott 1994). He borrowed from Paul Tillich the notion that religion is the depth of culture and culture the form of religion, a notion amplified by Reinhold Niebuhr and Langdon Gilkey (Tillich 1951-1963, 3: 158). Scott applied this notion–the depth of culture–effectively to his literary criticism. Not only did this provide a new set of insights regarding literature, it also enriched theology.

“Christian theology, as a result of its dialogue with great literature of the modern period, will find itself more richly repaid (in terms of deepened awareness of both of itself and of the age) than any other similar transaction it may undertake.” (Scott 1994) [2]

What I so appreciated as a student was the way Scott could make transparent the religious depth hidden beneath secular surfaces. Scott asked Tillich’s question: what is ultimate? Scott did not ask any questions about science. But I certainly do.

May we expand Theology & Literature into Theology, Science & Literature? A Scott student now a professor at Baylor University, Ralph C. Wood, gives us permission. “Both scientific and religious knowledge flourish when they engage present concerns by way of antecedent experience, and thus as they formulate judgments and principles via constant modification and enlargement. “ (Wood 2012, 31). London the fictional author provides the low hanging fruit of “antecedent experience” which the public theologian will find easy picking.

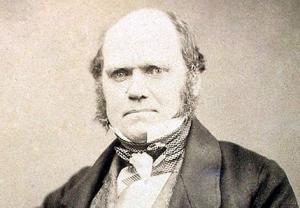

As you will soon see, I plan to ask questions about science. When we turn to America’s most widely read author of the first quarter of the twentieth century, Jack London, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution explodes like fire works on the 4th of July. Without attending to the science, the reader could not grasp London’s anthropology. It is in the evolutionary anthropology where we find religious depth.

The Wolf Within Us

In 1915, the father of depth psychology, Sigmund Freud drew a conclusion Jack London had arrived at two decades earlier. “The ‘primitive, savage and evil impulses of mankind have not vanished in any individual,’ but are simply waiting for the opportunity to show themselves again.”

Now to our topical question: does a ravenous wolf lurk within each of us? Only some of us? Must we remain ever alert to the danger that our repressed evolutionary past will surge forth in viciousness, chaos, destruction? Is our civilized order threatened at every moment with dissolving into a cauldron of primeval violence?

Jack London thought so while in Alaska during the Klondike God Rush, 1896-1899. Today, we ask with London: do both dogs and humans bear the genes of a common ancestor, the wolf? If so, must our future be determined by our evolutionary past?

There is more. Much more. The prescient Jack London a century ago asked a very contemporary question: did interstellar travelers intervene in Earth’s evolution in order to accelerate human development? Are we Homo sapiens a hybrid progeny of terrestrial apes and extraterrestrial geneticists? If so, why does the ravaging world still growl within the terrestrial soul?

Or, to put it another way, should we spend more time in front of our TVs watching “Ancient Aliens”?

Can we redeem the wolf within?

On the one hand, according to London, today’s Homo sapiens could without notice suddenly revert to our ravenous wolf past. On the other hand, according to London, Jesus points us to an egalitarian, humane, and socialist future. London had considered writing a short story about Jesus. Then, he thought better of it and abandoned the idea (Williams, Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1902-1907. 2021, 37).

Let’s say this again. On the one hand, Charles’ Darwin’s law of “natural selection” or Herbert Spencer’s “survival of the fittest” incarcerates Homo sapiens in a primeval past from which we can never on our own escape.

On the other hand, the science of Marxist socialism—which enamored London the labor organizer–promises human transformation. It promises temporal transcendence. It promises an egalitarian, prosperous, and humane future. Redemption will come through revolution.

London was an supporter of the Bolshevik momentum leading to the revolution of 1917 in Russia. He endorsed Marxist socialism. The Call of the Wild became required reading for school children for many years in both the Soviet Union and Maoist China. Jack London’s name is engraved on a wall in the Kremlin. Just how, we ask, can we reconcile London’s atavism via evolution with his anticipation of a post-revolutionary utopia?

So, which is it? Are we imprisoned in our past or liberated for our future? That is the human struggle that points us to religious depth. At least as deep as London can dig.

Here, in this small bite, is the fare garnished and served up in thirty-nine books and countless short stories by California’s notorious author, Jack London (1876-1916). Just a little more than a century ago, this adventurer and novelist literally penned three fictional accounts of what I dub, “The Wolves of Jack London.”[3] The troika includes The Call of the Wild (1903), White Fang (1904), and The Sea-Wolf (1906). Whether in dogs or in their human masters, the convulsive combination of love for life and vicious cruelty surges up from the primordial Wild still lurking within us.

For London there are “connections among evolutionary theory, criminality, and primitivism,” observes Jay Williams. “The impulse to commit crime is something that comes out of the mysterious unknown, or the unconscious” (Williams, Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1902-1907. 2021, 270). Theologians will think about original sin or even inherited sin here. Theologians will also think about the relationship between natural evil and moral evil.[4] But this is not London’s vocabulary.

Reversion is perennially a threat. At any moment we humans or our dogs may revert to an atavistic heritage that has been apparently lost for a hundred generations. Primeval ferocity is ever ready to pounce. In the 1901 short story, “A Relic of the Pliocene,” a prehistoric mammoth appears and engages a Klondike hunter in a life-and-death struggle. At any moment, the dead past can live again. Still we ask: can we look forward to a future where that threat will be no more?

More than Evolution Requires

White Fang would comprehend a most striking line that appears in David Brooks’ new book, The Second Mountain. Speaking of her daughter, a young mother says to Brooks, “I found I loved her more than evolution required” (Brooks 2019, 42). Can the love we share as civilized beings rocket us up and off from our evolutionary launch pad? Or, is the gravity of our ancestral instinct for survival so strong that we’ll inevitably crash back to earth strewn with tooth gnawed bones?

Nature is blood “red in tooth and claw,” averred Alfred Lord Tennyson in the dinosaur canto of his In Memoriam in the middle of the nineteenth century. According to Michael Lundblad, the law of the jungle later in the nineteenth and early in the twentieth century meant “the behavior of wild animals can be equated with natural human instincts not only for competition and reproduction but also for violence and exploitation” (Lundblad 2013, 1). Is today’s civilization condemned to remain in the past, governed solely by natural selection or the survival-of-the-fittest?

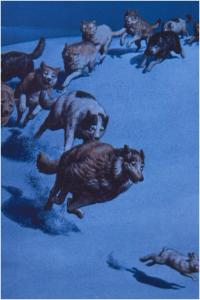

The Call of the Wild & versus the Call of Civilization

To repeat the theme: the dog becomes a wolf in The Call of the Wild. Buck, a dog from San Francisco goes to Alaska during the gold rush of the 1890s. Instincts hitherto repressed by domestication rush into Buck’s consciousness, instincts borne through millions of evolutionary years. “He must master or be mastered; while to show mercy was a weakness. Mercy did not exist in the primordial life. It was misunderstood for fear, and such misunderstandings made for death. Kill or be killed, eat or be eaten, was the law; and this mandate, down out of the depths of Time, he obeyed.” Like Plato’s Meno, Buck the dog was learning what he already knew from a previous incarnation as a wolf.

After his reversion to the wolf, Buck was chasing a rabbit.

“All that stirring of old instincts, which at stated periods drives men out from the sounding cities to forest and plain to kill things by chemically propelled leaden pellets, the blood lust, the joy to kill—all this was Buck’s, only it was infinitely more intimate. He was ranging at the head of the pack, running the wild thing down, the living meat, to kill with his own teeth and wash his muzzle to the eyes in warm blood.” (London, The Call of the Wild 1903)

Note that it is not only Buck the dog who washes his muzzle in warm blood. So does the human race.[5]

After The Call of the Wild, What’s Next?

Philosophically, Jack London was a naturalist. Any naturalistic perspective in our post-Darwinian era must recognize that nature is blood “red in tooth and claw,” that survival-of-the-fittest determines the winners in the struggle for existence, that killer animals are our ancestors, and that their propensity for violence lives on in Homo sapiens.

Can we ground our ethics in nature understood this way? If nature alone is to provide a foundation for human ethical deliberation, must we construct our ethical superstructure on this evolutionary inheritance? The result would be wolf ethics. In short, a Darwinian naturalist would have no inclination to be nice. How might a public theologian assess this?

What’s next in our Patheos Public Theology series on Jack London? White Fang. Whereas Buck in The Call of the Wild is a dog who goes to Alaska and becomes a wolf, White Fang is a wolf in Alaska who moves to California and becomes a dog. Look for the next post in this Patheos series on the wolves of Jack London.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching theology and ethics. He specializes in the creative mutual interaction between science and theology. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and Patheos column on Public Theology, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/.  Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] This series on the evolutionary worldview of Jack London is drawn from my forthcoming book, The Voice of Christian Public Theology, with ATF Press.[2] I remained a disciple of Nathan Scott even after studying with Giles Gunn, who sought to pull the field out of the depths of ultimate concern into the shallowness of de rigor literary criticism. Mark the transition with David Jasper, editor of Literature and Theology (1992).

[3] Jack London “is established now as a major figure in American literary history…No other writer, not even our beloved Mark Twain, has so thoroughly captured the essential themes of the American Dream in his meteoric career–and none has so completely captivated American readers of all ages” (Labor, 223). I recommend readers of this series on the “Wolves of Jack London” to visit the Jack London Society website.

[4] Theologians frequently distinguish between natural evil at the animal level and moral evil at the human level. Can moral evil be reduced to natural evil? Darwinian evolution seems to imply this. London assumes this to be the case. Theologians remain perplexed by mystery. “The ultimate purpose of both evolutionary and moral evil is indeed still deeply shrouded in mystery. God’s ways will always transcend those of humanity and nature, and for now we must content ourselves with seeing through a glass darkly” (Moritz 2008, 188).

[5] My interpretation of Jack London posits that the wolf is a cipher for the human. Is this realistic? Not for some literary critics. This is because of the incommensurability of the animal worldview and the human worldview. Just ask Jacques Derrida.

“I. Incontestably, animals and humans inhabit the same world, the same objective world even if they do not have the same experience of the objectivity of the object … 2. Incontestably, animals and humans do not inhabit the same world, for the human world will never be purely and simply identical to the world of animals … 3. In spite of this identity and this difference, neither animals of different species, nor humans of different cultures, nor any animal or human individual inhabit the same world as another … the difference between one world and another will remain always unbridgeable, because the community of the world is always constructed, simulated by a set of stabilizing apparatuses … nowhere and never given in nature.” (Derrida, 2009, 8-9)

When applying Derrida’s view of worldview, Hannah Strømmen tries to reestablish human-animal continuity minus human sovereignty over the animals.

“If part of animal studies is attempting to think ‘the animal’ outside a logic of human sovereignty, and to attempt to rethink human—animal relationships outside, or other to, such a discourse of power, then a different kind of discourse is needed that can do precisely that” (Strømmen, 2017, 408).

The power that humans exert over their dogs and other animals in Jack London’s stories stresses both human cruelty and human kindness. Both exemplify sovereignty. Yet, both are intended to convey the wolflike traits still operative at the human level.

References

Basket, Sam. 1996. “Sea Change in The Sea Wolf.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassato and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 92-109. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Berkove, Lawrence. 2004. “Jack London and Evolution: From Spencer to Huxley.” American Literary Realism 36:3 243-255.

Berkove, Lawrence. 1996. “The Myth of Hope in Jack London’s “The Red One”.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassuto and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 204-216. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Brandt, Kenneth. 2018. “Jack London: An Adventurous Mind.” In Jack London, by Kenneth K. Brandt. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press (Northcote).

Brooks, David. 2019. The Second Mountain. New York: Random House.

Derrida, Jacques. 2009. The Beast and the Sovereign. Vol. I, trans. Geoffrey Bennington. Chicago, IL and London: University of Chicago Press.

Deudney, Daniel. 2020. Dark Skies: Space Expansionism, Planetary Geopolitics, and the Ends of Humanity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, James. 1978. “A New Reading of The Sea Wolf.” In Jack London: Essays in Criticism, by ed Ray Wilson Ownbey, 92-99. Santa Barbara CA: Peregrine Smith.

Faulstick, Dustin. 2015. “The Preacher Thought as I Think.” Studies in American Naturalism 10:1 1-21.

Kean, Sam. 5/6/2011. “Red in Tooth and Claw Among the Literati.” Science 332 654-656.

Labor, Earle. 1996. “Afterword.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassuto and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 217-223. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Leder, Steve. 2019. “The Beasts Within Us.” Time Special Edition on The Science of Good and Evil 84-87.

London, Jack. 1903. The Call of the Wild.

—. 1916. The Red One.

—. 1906. The Sea Wolf.

—. 1904. White Fang.

Lundblad, Michael. 2013. The Birth of a Jungle: Animality in Progressive Era US Literature and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moritz, Joshua. 2008. “Evolutionary Evil and Dawkins’ Black Box.” In The Evolution of Evil, by Martinez J Hewlett, Ted Peters, and Robert John Russell, eds Gaymon Bennett, 143-188. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 1941. The Nature and Destiny of Man, 2 Volumes. New York: Scribners.

Oliveri, Vinnie. 2001. “Sex, Gender, and Death in The Sea Wolf.” Pacific Coast Philology 38 99-115.

Reesman, Jeanne Campbell. 2012. “The American Novel: Realism and Naturalism.” In A Companion to the American Novel, by ed Alfred Bendixen, 42-59. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Scott, Nathan. 1994. “A Ramble on a Road Taken.” Christianity and Literature 43 (2): 205-212.

Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S., et.al. 2020. “Arctic-adapted dogs emerged at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition.” Science 368:6498 1495-1499.

Stasz, Clarice. 1996. “Social Darwinism, Gender, and Humor in Adventure.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassuto and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 130-140. Stanford CA: Standord University Press.

Strømmen, Hannah. 2017. Literature and Theology 31:4: 405-419.

Tillich, Paul. 1951-1963. Systematic Theology. 1st. 3 Volumes: Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilkinson, David. 2013. Science, Religion, and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Jay. 2014. Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1893-1902. Lincoln NB: University of Nebraska Press.

—. 2021. Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1902-1907. Lincoln NB: University of Nebraska Press.

Wood, Ralph. 2010. “Flannery O’Conner, Benedict XVI, and the Divine Eros.” Christianity and Literature 60:1 35-64.

Wood, Ralph. 2012. “The Lady in the Torn Hair Who Looks on Gladiators in Grapple: G.K. Chesterton’s Marian Poems.” Christianity & Literature 62:1 29-55.

Zuber, Devin P., 2019. The Language of Things. Charlottesville VA: University of Virginia Press.