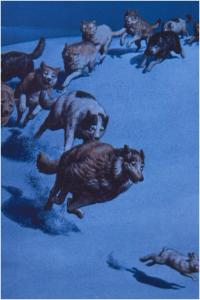

The Wolves of Jack London

Jack London 5: Wolf Pack Ethics

Post-Darwinian Ethical Naturalism

What about lone wolf ethics, historically known as Social Darwinism? What about wolf pack ethics, technically known as reciprocal altruism? Can we ask nature in one of these two forms to provide our moral norms? Can we construct and ethical naturalism by emulating wolf behavior?

In this series of posts on “The Wolves of Jack London,” we’ve been wading into the waters of the academic field called Literature and Religion or Theology and Literature. Because of London’s reliance on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, we’re pausing at the confluence of literature, science, and theology to float options for constructive ethics. We’re giving consideration to ethical naturalism.

Jack London was a naturalist. So, we have been exploring paths to ethical naturalism. The fundamental structure of deontologicl naturalistic ethics is to base what we ‘ought’ to do on what already ‘is’ in nature. When it comes to teleological ethics, we ask nature to tell us what the good is for which we want to strive. Each of these is problematic, because ethics normally envisions a future that is different from the present—that is, what we ‘ought’ to do is transform what ‘is’ into something better.

“Ethics is the science of man’s moral existence, asking for the roots of the moral imperative, the criteria of its validity, the sources of its contents, the forces of its realization,” is a description of ethics given us by Paul Tillich (Tillich, 1960, 72). In this post, we’re engaged in constructive ethics.

London’s evolutionary lycanthropy hints at an ethical naturalism based upon the wolf that lurks within the human soul. Let’s follow our exploratory trail beginning with the wolves of Jack London leading toward what Tillich identifies as the “moral imperative.”

THE WOLVES OF JACK LONDON / Jack London Society

Jack London 1: The Call of the Wild

Jack London 4: Lone Wolf Ethics

Jack London 5: Wolf Pack Ethics

Jack London 6: Wolf and Lamb Ethics

The ethical naturalist restricts the good to something discoverable within nature. “Naturalists would in general abstain from supplementing natural reality with supranatural determining factors….[Nature is] complete, without theologically relevant holes,” Dutch religious naturalist Willem Drees tells us (Drees, 2003, 594). To play by the naturalist’s rules, no appeal to God is allowed. Appeal to God or anything beyond the what-is in nature would be cheating.

With this in mind, we are exploring three ways to derive the moral norm from nature: (1) lone wolf ethics; (2) wolf pack ethics; and (3) lamb & wolf ethics. In this post, our task will be to explicate wolf pack ethics.

From Lone Wolf to Wolf Pack Ethics

In a previous post, we explicated lone wolf ethics. The lone wolf exemplifies nature as blood “red in tooth and claw.” Charles Darwin describes this as “natural selection” and Herbert Spencer as “survival of the fittest.” The wolf as predator provides the cipher for this form of naturalistic ethics. Lone wolf ethics characterized Social Darwinism, Eugenics, and Nazism, wherein the in-group preys on the out-group. Now, we ask: what goes on within the in-group?

Charles Darwin himself took a stab at ethical naturalism, selecting from nature wolf pack ethics rather than lone wolf ethics. “As man advances in civilization and small tribes are united into larger communities, the simplest reason would tell each individual that he ought to extend his social instincts and sympathies to all the members of the same nation, though personally unknown to him”(Darwin, 1874, 126).

Note what Darwin is doing here. He first describes natural social instincts and sympathies within the tribe, within the wolf pack. Then, secondly, he prescribes extending these beyond the tribe to the nation. Not the world as a whole. Just the nation. The world beyond the nation would remain an out-group, one supposes.

Darwin constructs his ought on the basis of what already is a property of human nature. In brief, Darwin’s ethical naturalism proffers Wolf Pack Emulation Ethics.[1]

“Man is by nature a political animal,” we remember Aristotle saying (Aristotle, Politics, 1:125a). If this is the case, might the wolf pack provide a better analogy for human civilization than the lone wolf? Might reciprocal altruism expostulated by sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists provide grounding for ethical naturalism?

Ethical Naturalism Form Two

Reciprocal Altruism in Wolf Pack Ethics

What Spencer, Galton, and Hitler share in common is a nature ethic with two premises: (1) nature is violent just as Tennyson described it, namely, blood “red in tooth and claw”; and (2) our moral responsibility is to emulate nature in society. We’ve called this Lone Wolf Emulation Ethics. We’ll use the label, Wolf Pack Emulation Ethics, to apply to reciprocal altruism in the form of cooperation within the social group of animals. The TV show, Sixty Minutes, calls this “survival of the friendliest.”

The difference between the two is that contemporary sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists alter the first premise. They look at the same biological world through the same evolutionary lenses, to be sure. But they see something different. What they notice about the struggle for existence is cooperation, even altruism.[2] The lone wolf is selfish. The wolf pack is selfish in relation to every creature outside the pack. Yet, cooperation and altruism within the group increases the group’s survivability. “Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary” (Kohn, 11/20/2008, 297). That is to say, group selection for survival benefits from in-group cooperation and reciprocal altruism.

In pre-human societies of insects and rodents, altruistic behavior has contributed to victory in the battle for adaptive success. Could nature’s pattern of cooperation apply to humans? Yes. High minded moral norms fostering cooperation around which human culture has been constructed can provide Homo sapiens with an adaptive advantage. From nature we are now learning how to be altruistic; whereas a century earlier we were learning how to defeat our neighbors in the battle for survival. Wolf pack Social Darwinists select from nature not competition but rather cooperation. In both cases, curiously, the respective value system is rooted in nature, in the same history of biological evolution (Ruse, 2001).

According to the science of compassion school of thought, empathy as an emotion becomes motivation for altruism understood as a behavior. The empathy-altruism hypothesis “claims that empathic concerned (defined as other-oriented emotion elicited by and congruent with the perceived welfare of another in need) produces altruistic motivation (a motivational state with the ultimate goal of increasing the other’s welfare)” (Batson, 2017, 27).

How did compassion evolve? Answer: mammalians, including our species, learned empathy-altruism from child rearing. “If mammalian parents had not been intensely interested in the welfare of their vulnerable progeny, these species would have quickly died out” (Batson, 2017, 30). This is speculative, to be sure. Yet, it sounds scientific. Might one construct a naturalistic ethic on this apparently scientific revelation about our evolutionary origins?

Scratch an altruist and watch a hypocrite bleed.

How does wolf pack ethics look to the sociobiologist, evolutionary psychologist, or behavior ecologist? Recall the basic assumption of these heirs to Darwin: we human beings as individuals and as families are conscripted soldiers fighting in the genetic war. When we try to defeat our competitors, we are being used by our genes to checkmate their competitors. Every aspect of our lives—our loving and hating, our fighting and cooperating, our giving and stealing, our greed and generosity—are but subplots in the larger evolutionary drama of genome versus genome combat. When in our daily life we experience ourselves acting selfishly, we can appeal to an underlying biological explanation. We are selfish because our genes our selfish.[3][4]

Human daily life is by no means limited to selfish behavior, to be sure. We have our moments of caring, of devotion, of high-minded sharing and cooperation. Within the family group, reciprocal caring takes place. This too finds a sociobiological explanation, the same explanation. Our caring and sharing are explained as ‘kin altruism’ and ‘reciprocal altruism’.

In the wolf pack model, the selfish gene uses our altruistic behavior to perpetuate itself. How? Because the selfish gene can use groups: kin, families, tribes, races. Within a kinship group which shares the same DNA sequence, individuals can cooperate with one another and even in rare instances sacrifice themselves on behalf of their loved ones’ safety. The sacrifice of one individual so that other individuals can reach reproductive age and have babies still counts as a success for the selfish gene. The gene will successfully replicate itself as long as the survivor of a crisis bears the preferred genetic code.

Two kin groups might cooperate for the adaptive benefit of both. That’s where we apply the term, ‘reciprocal altruism’. Reciprocal altruism remains the province of the selfish gene, at least according to these schools of evolutionary thought.

The logic here demands careful scrutiny. Altruism, according to selfish gene Darwinians, occurs within a range of genetic continuity. You only sacrifice lovingly for someone who shares most of your DNA sequences. So, those showing altruistic behavior towards one another share some specific DNA sequences, such as family members or even clan members. Outsiders—that is, organisms or tribes that do not share the DNA sequence in question—do not deserve self-sacrificial service. Self-sacrificial service remains within genetic limits. No altruism is expected for strangers or aliens or anyone outside the genetically determined family, clan, tribe, or race.

Altruistic behavior is actually selfish behavior in disguise. It promotes the long term goal of the selfish gene, namely, to perpetuate its own DNA sequence. Even though at the level of the organism altruism may appear to us to be virtuous, the underlying drive of the gene to replicate is relentless and pitiless. Robert Wright contrasts the resulting evolutionary ethic with love in the theological sense.

“Brotherly love in the literal sense comes at the expense of brotherly love in the biblical sense; the more precisely we bestow unconditional kindness on relatives, the less of it is left over for others” (Wright R. , 1994, 160).

Or, much more pungently, “Scratch an ‘altruist’, and watch a ‘hypocrite’ bleed” (Ghiselin, 1974, 247).

E.O. Wilson on Xenophobia

Even in a community enjoying kin or reciprocal altruism, our killer ape genes–our lone wolf genes–lead us to xenophobia. According to Edward O. Wilson, “Human beings are strongly predisposed to respond with unreasoning hatred to external threats and to escalate their hostility sufficiently to overwhelm the source of threat by a respectable wide margin of safety. Our brains do appear to be programmed to the following extent: we are inclined to partition other people into friends and aliens” (Wilson, 1978, 122). A universal ethic of care and service let alone the idea of a common good cannot be grounded in our genetic inheritance.

To summarize theologically: kin altruism and reciprocal altruism fall short of offering love—at least the agape love we know from Jesus’ teachings–for the benefit of an outsider. To extend this loving service to someone who is other, to someone outside the kinship circle or outside the circle of reciprocators, simply does not fit this explanatory model. “Much as we wish to believe otherwise,” comments selfish gene theorist Richard Dawkins, “universal love and the welfare of the species as a whole are concepts that simply do not make evolutionary sense” (Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, 1976, 1989, 2).

Might Wolf Pack Ethics be theologically attractive?

Some liberal clergy find this form of naturalism attractive. Here is how a contemporary Unitarian Universalist minister, Anthony David, sorts it out. On the one hand, the lone wolf or killer ape theory holds that “there exists a murderous force within us, so alien to all that we hold sacred and holy, so untrue to the teachings of our greatest prophets, so alien to our hopes for peace and justice for all, so irreconcilable with the idea that people have inherent worth and dignity” (David, 2009, 7).

On the other hand, conjectures Anthony David, the pre-human altruism theory provides an alternative view. Note the term ‘killer ape’ is substitute for our ‘wolf’ terminology.

“Biologists have documented in bonobos—as well as in chimpanzees and gorillas—kindness and empathy, a capacity for peacemaking and reconciliation, creativity, even freedom…Our human heritage, exemplified in our closest animal relatives is mixed….Our inner ape is not just one narrow thing, as ‘killer ape’ theory suggests. What’s deep down in human nature is broad: as much love and compassion as it is murder. And our job is to choose wisely which impulses to draw on” (David, 2009, 32).

We have inherited from our evolutionary history two competing impulses, the killer ape impulse and the altruistic impulse. We can choose between them. Regardless of which we choose, we will be emulating nature.

How might a theologian critique Wolf Pack Ethics?

Astute systematic theologian Sarah Coakley appreciates the lifting up of cooperation and altruism found in nature. But, Coakley claims, this discovery alone is insufficient to ground a social ethic let alone a Christian ethic. We need middle axioms of a metaphysical type to move from the is of nature to the ought of human ethics. “What mathematical biology tells us about ‘cooperation’ and its human variant, ‘altruism’, is hugely suggestive for ethical and political reflection, to be sure;” she writes. But, there is a caveat.

“Various further stages of philosophical decision have to occur before any political conclusions can legitimately be drawn…To repeat: there is no straightforward move from ‘scientific’ deliverances on cooperation to ethical or political implications” (Coakley, 2013, 138).

Why are there no straightforward paths from science to ethics? Because evolutionary biology is ambiguous. On the one hand, it is blood red in tooth and claw. On the other hand, primitive forms of interspecies cooperation can be found, as well as moments of reciprocal altruism. For human society to emulate nature, we humans must select which of these two options should apply. This means that if we ask nature to tell us what is moral, we the listeners must select which of the alternatives we deem to be moral. This places the grounding of human ethics within human subjectivity. Nowhere else. In short, evolutionary theory cannot alone define our ethics for us.

Ethical Naturalism: What’s Next?

We ask nature to tell us what the good is when constructing both Lone Wolf Ethics and Wolf Pack variants on ethical naturalism. In both cases we ought to emulate what nature already does. But, neither of these naturalistic ethical programs can justify seeking the common good let alone the good of the stranger or the enemy. Must the constructive ethicist defy nature by lifting up a vision of the good that transcends nature? That’s where we turn next to address Wolf & Lamb Ethics.

▓

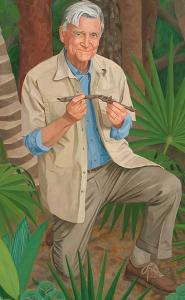

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). Along with Martinez Hewlett, he co-authored three books on the evolution controversy. Along with Martinez Hewlett, Joshua Moritz, and Robert John Russell, he co-edited, Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Intelligence (2018). Along with Octavio Chon Torres, Joseph Seckbach, and Russell Gordon, he co-edited, Astrobiology: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy (Scrivener 2021). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com. In the near future he will publish, The Voice of Christian Public Theology with the Australian Theological Forum.

▓

[1] Once again, we must flag the naturalistic fallacy. The fallacy comes in two overlapping forms. The David Hume form of the fallacy bases an ought on an is. It’s a slight of hand. When describing how something is, the moralist slips into prescribing how it ought to be. One dare not base an ought on an is, according to the Humean variant. The G.E. Moore form of the

fallacy asks nature to tell us what the good is. Describing nature cannot all by itself prescribe what the good is, said Moore a century ago. “Moore thought that the good was a non-natural property possessed by good things,” writes J. Baird Callicott. “Some things are intrinsically good; others are instrumentally good, because they are products of intrinsically good things….To commit the Naturalistic Fallacy is to claim that exhibiting some natural property is what makes something good”(Callicott, 2013, 70-71). Callicott wants to bypass the naturalistic fallacy in order to ground an eco-ethic on Earth’s natural properties. The take away of all this of us here is this: neither Lone Wolf Emulation Ethics nor Wolf Pack Emulation Ethics escapes the naturalistic fallacy.

[2] Lone Wolf Ethics treats egoism and selfishness on behalf of survival as the good. Wolf Pack Ethics looks for examples of altruism already within evolution. A theory of kin altruism began to develop in the 1960s, well before the Human Genome Project. Accordingly, organisms will behave altruistically toward other organisms that share the same genome. They will behave destructively toward other organisms that are genetically distant. According to Jerry Osinksi, “a key step in understanding altruistic behavior is to take into account the degree of relatedness between benefactor and beneficiary. The higher the co-efficient of relatedness, the greater the probability that offering help will contribute to the survival of genes promoting altruism. A single act of altruism may benefit more than one related beneficiary, which increases its profitability from the genetic perspective.” This provides, allegedly, a scientific explanation for in-group loyalty and out-group hostility. This is disappointing for the constructive ethicist, because there is no warrant for appeal to the common good in this theory.

[3] The selfish gene theory was given us by Richard Dawkins. Now, he does not actually refer to the gene itself. Rather, Dawkins contends that it is the DNA sequence–which includes both genes and junk DNA–which drives natural selection. (Dawkins, 1976).

[4] Regarding Richard Dawkins’ selfish gene explanation for natural selection, Parisa Moosavi at the University of Toronto is criticval. “Gene Selectionism, which puts genes at the center of evolutionary change and almost eliminates the role of organisms, is in fact disputed in philosophy of biology” (Moosavi, 2016, p. 44).

References

Barnes, E. W. (1927). Should Such a Faith Offend? Sermons and Addresses. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Batson, D. (2017). The Empathy-Altruism Hypothesiis. In E. S.-T. Emma M Seppala, The Oxford Handbok on Compassion Science (pp. 27-40). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bennett, G., Hewlett, M., Peters, T., & Robert John Russell, e. (2008). The Evolution of Evil. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Bowler, P. (2007). Trials and Gorilla Sermons: Evolution and Christianity from Darwin to Intelligent Design. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Callicott, J. B. (2013). Thinking Like a Planet. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coakley, S. (2013). Evolution, Cooperation, and Ethics. Studies in Christian Ethics 26:2, 135-139.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. London: Murray.

Darwin, C. (1874). The Descent of Man. London: Murray.

David, A. (2009). Our Inner Ape. UU World.

Dawkins, R. (1976, 1989). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1986). The Blind Watchmaker. London: WW Norton.

Delio, I. (2020). Theology of Nature or Relational Holism: Building on Teilhard’s Vision. In e. Ted Peters and Marie Turner, God in the Natural World: Theological Explorations in Appreciation of Denis Edwards (pp. 171-191). Adelaide: ATF.

Desmond, A. (1997). Huxley: Evolution’s High Priest. London: Michael Joseph.

Drees, W. (2003). Naturalism. In e. J Wentzel Vrede van Huyssettn, Encyclopedia of Science and Religion (pp. 593-597). New York: Macmillan, Thomson, Gale.

Edwards, D. (2020). Review of Ted Peters. In e. Anthony Kain and Hilary Regan, Denis Edwards in His Own Words (pp. 371-374). Adelaide: ATF.

Fest, J. (1975). Hitler. New York: Random House / Vintage.

Galton, F. (1892). Hereditary Genius. London:: McMillan.

Ghiselin, M. (1974). The Economy of Nature and the Evolution of Sex. Berkeley and Los Angeles CA: University of California Press.

Haeckel, E. (1905). The Wonder of Life. New York: Harper.

Hitler, A. (1925, 1971). Mein Kampf tr Ralph Manheim. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Hofstadter, R. (1944). Social Darwinism in American Thought. Boston: Beacon.

Hume, D. (1888). A Treatise on Human Nature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Huxley, T. (1880). The Coming of Age of the Origin of Species. Science 1, 15-17 + 20.

Huxley, T. (1896). Evolution and Ethics. Amherst NY: Prometheus.

Kohn, M. (11/20/2008). The Needs of the Many. Nature 7220:456, 296-299.

Løgstrup, K. (1997). The Ethical Demand. Notre Dame IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Luther, M. (2015-2020). The Freedom of a Christian. In M. Luther, The Annotated Luther, 5 Volumes (pp. 1: 467-518). Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Moltmann, J. (2003). Science and Wisdom. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Moore, G. E. (1903, 1959). Principia Ethica. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Moosavi, Parisa, 2016. “On the Relevance of Evolutionary Biology to Ethical Naturalism.” The Ethics of Nature and the Nature of Ethics. Ed. Gary Keogh. Lanham MA: Lexington.

Nisson, U. (n.d.). Naturalistic Fallacy. In e. Wentzel Vrede Van Huyssteen, Encyclopedia of Science and Religion 2 Volumes.

Pannenberg, W. (1969). Theology and the Kingdom of God. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Peirce, C. S. (1931-1958). Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, 2 Volumes. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press.

Peters, T. (2nd Ed, 2003). Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom. London and New York: Routledge ISBN0-415-94248-0-415-94249-7.

Peters, T. a. (2005). Evolution from Creation to New Creation. Nashville TN: Abingdon.

Pope, S. (2007). Evolution and Christian Ethics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Proctor, R. (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Ruse, M. (2001). Evolution. In e. Lawrence C Becker and Charlotte B Becker, Encyclopedia of Ethics (pp. 501-503). London: Routledge.

Sanger, M. (1917). Birth Contol and Women’s Health. Birth Control Review 1:12.

Spencer, H. (1879). The Data of Ethics. New York: A L Burt.

Spencer, H. (1897). First Principles. New York: D Appleton.

Tillich, P. (1960). Love, Power, and Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, E. O. (1978). On Human Nature. New York: Bantam.

Wright, N. (2006). Evil and the Justice of God. London: SPCK.

Wright, R. (1994). The Moral Animal. New York: Random House.