The Wolves of Jack London

Jack London 6: Wolf and Lamb Ethics

Post-Darwinian Naturalism & Ethical Thinking

In this series of posts reflecting on the wolf trilogy of Jack London, we’ve been seeking a ground for our ethical vision. Because Jack London was a naturalist, we tried on two forms of naturalistic ethics to see if they fit: (1) lone wolf ethics and (2) wolf pack ethics. Here in this post, we’ll try on (3) wolf & lamb ethics. We will take a giant step from evolution to eschatology, from inheritance to hope.

Here is our trail we’ve been blazing through the ethical wilderness from wolf to civilization.

THE WOLVES OF JACK LONDON / Jack London Society

Jack London 1: The Call of the Wild

Jack London 4: Lone Wolf Ethics

Jack London 5: Wolf Pack Ethics

Jack London 6: Wolf and Lamb Ethics

Theology and Literature

As an exercise in public theology, we’re pursuing our task within the academic field of Theology and Literature. Let’s begin with a brief reflection on Genesis 2:7.

“Then the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being.”

As you can readily see, we human beings are a blend of soil and spirit. Molded from clay, God breathed life into us. And we became living beings. Our bodies are grounded in the soil while our restless spirits soar to the heavens seeking transcendence. In evolutionary terms, we have inherited what the wolves have inherited.

On the one hand, rooted in the soil, we are natural beings through and through. We are nature. And nature is us.

On the other hand, alive because of God’s spirit breathing within us, we yearn for something more than nature can deliver. We envision a redeemed nature, a transformed nature. Teleological ethics begins with a vision of a future good that is more than nature as we’ve inherited it can deliver. Toward that good we strive.

Ilia Delio, who is very sympathetic to incorporating Darwinian evolution into our theological understanding, strives for more than what nature has given us. “Our responsibility for evolution requires more than passing on a world no worse than the one we have inherited. Rather, a morality of movement requires a morality of involvement, one by which we improve the world” (Delio, 2020, 191).

Form Three: Wolf and Lamb Ethics

The Wolf & Lamb form of ethical grouding begins with reflection on the eschatological vision of the Peaceable Kingdom in Isaiah 11:6.

The wolf shall live with the lamb,

the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

and a little child shall lead them. (Isaiah 11:6)

Even though our evolutionary inheritance has bequeathed to Homo sapiens the drive of the selfish genome that leads to the lone wolf and the wolf pack, we should defy our genetic inheritance and pursue a universal altruistic and communitarian social ethic. Rather than pursue the good of the lone wolf or the good of the wolf pack, wolf & lamb ethics pursues the global common good.

Our vision of the Peaceable Kingdom is not something we inherit from our evolutionary past. Rather, the Peaceable Kingdom comes from the future. It comes from the advent of something new.

“See, I am doing a new thing,” announces God in Isaiah 43:19. The good for which God strives is not grounded in the ‘what-is’ of nature’s past. Our ethical ‘ought’ should be based on the new thing for which God strives.

Angie, the Wolf’s Descendent

Dogs are descended from wolves. On occasion today’s dog can lie down peacefully with another animal that was once the wolf’s prey.

The doggie that lives with my family these days is named, Angie. Although a mutt, it’s clear she has the genes of a Cairn Terrier. While writing this essay, Angie entered the room. She went to her small toy box and selected an item. It was a leather chewy. She picked the chewy up in her mouth and came over to me. She presented the chewy as a gift to me. I took it into my hand. I thank her ceremoniously. Then, Angie curled up for a nap. Is this an example of animal altruism?

This breed of dog like all others evolved from wolves in less than 12 thousand years. Does Angie think of my family as her wolf pack, wherein she practices cooperation and altruism? Does Angie’s animal altruism count as an advance in evolution?

We must still ask: does the predatory wolf still lurk within Angie? You betcha! Watch her chase neighborhood racoons, squirrels, and rabbits.

Recall my story of Buck the Siberian Husky in the second post of this series, White Fang. Our domesticated pet, Buck, killed our lamb-like rabbit just as London’s Buck did in The Call of the Wild.

Now, the naturalistic ethicist must choose between two animal traits: rabbit predation or chewy altruism. But in making this choice, we recognize that the ground for naturalistic ethics lies in the human choice-making and not in the natural realm itself. Nature simply does not tell us what is good or right or true.

Of the two premises held by rabbit-killing lone wolf ethics and cooperative wolf pack ethics—(a) nature employs violence so that the fit may survive and (b) human society should emulate nature—the wolf and lamb school alters the second premise. The view of our inherited nature is still that of Tennyson, red in tooth and claw, to be sure. We human beings have biologically inherited the lone wolf or killer ape capacity for violence endemic to the struggle for survival. Despite this, the wolf and lamb school defies this inherited nature. It enjoins us to surpass our biological inheritance to pursue social justice and cultivate an ethic of universal respect and care.

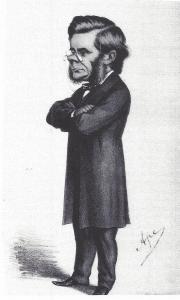

Darwin’s Bulldog: Thomas Henry Huxley

We find wolf and lamb ethics evolving—excuse the pun—in the thought of the man known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” and “Evolution’s High Priest,” Thomas Huxley. Huxley engaged in a career-long battle with the hegemony of the Anglican Church (Desmond, 1997). His initial reading of Darwin’s Origin, along with his subsequent reflections, convinced him that this explanatory model for the development of the living world provided just the ammunition needed to strike a decisive blow against the ecclesiastical grip that ruled British society.

By the 1880s, Huxley was using religious terminology to describe culturally what had become of Darwin’s biological theory (Huxley, 1880). He called evolution a “doctrine” and those working in the field “disciples” who were occupied in spreading and developing evolution’s “doctrines.” This sentiment is echoed two generations later by Huxley’s grandson, the evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley, who saw in evolution “the lineaments of a new religion.” Evolutionary theory was supplanting religion; or, perhaps more precisely, Darwinism was becoming a naturalistic religion to replace Christian hegemony in English speaking society.

Huxley’s naturalistic ethic did not turn callous or brutal. Should social progress emulate evolutionary precedents? No. Should human society follow the path already taken by biological evolution, according to which might makes right and only the fit survive. No. Rather, Evolution’s High Priest embraced modern liberal values such as cooperation and peace. He repudiated the notion that we could derive social ethics from nature’s precedents. Even if survival of the fittest has been the law of evolution up until this point, it would debase the human spirit to make this our moral guide. The state of nature ought not become the state of civilization. We human beings have transcended the brutality of our evolutionary past. We dare not appeal to survival of the fittest to justify temporary returns to that brutality. Even if the struggle to survive is a cosmic law, we must be of stout heart and establish a social order that defies that law.

Instead of blithely accepting a brutal survival-of-the-fittest ethic of the lone wolf, we should make fit as many as possible to survive.

“The practice of that which is ethically best—what we call goodness or virtue—involves a course of conduct which, in all respects, is opposed to that which leads to success in the cosmic struggle for existence. In place of ruthless self-assertion, it demands self-restraint; in place of thrusting aside, or treading down, all competitors, it requires that the individual shall not merely respect, but shall help his fellows; its influence is directed, not so much to the survival of the fittest, as to the fitting of as many as possible to survive” (Huxley, Evolution and Ethics, 1896, 81-82).

Atheist or Agnostic?

Thomas Huxley coined the word ‘agnostic’ to describe his position with respect to belief. Why not use the word ‘atheist’? For Huxley, the scholar, this was too conclusive, too definitive. Perhaps it seemed too presumptive for a scientist. Huxley would rather say “I don’t know” than espouse a defined position regarding God’s existence. Even so, materialistic naturalists in our era justify their atheism by appeal to Darwin’s work. Richard Dawkins proclaims in his book The Blind Watchmaker, “…although atheism might have been logically tenable before Darwin, Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist” (Dawkins, 1986, 6).

Thomas Huxley coined the word ‘agnostic’ to describe his position with respect to belief. Why not use the word ‘atheist’? For Huxley, the scholar, this was too conclusive, too definitive. Perhaps it seemed too presumptive for a scientist. Huxley would rather say “I don’t know” than espouse a defined position regarding God’s existence. Even so, materialistic naturalists in our era justify their atheism by appeal to Darwin’s work. Richard Dawkins proclaims in his book The Blind Watchmaker, “…although atheism might have been logically tenable before Darwin, Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist” (Dawkins, 1986, 6).

Excursus: The Naturalistic Fallacy

Relevant here is the naturalistic fallacy in its two closely related forms, Moore’s Maxim and Hume’s Hurdle. According to Moore’s Maxim: nature cannot tell us what the good is. According to Hume’s Hurdle, we cannot jump logically from what ‘is’ to what ‘ought’ to be. In neither case can we ask what ‘is’ in nature provide a moral norm for what we ‘ought’ to do.

Social Darwinism in both its lone wolf and wolf pack forms is traditionally called evolutionary ethics. The inescapable problem with an evolutionary ethic is that it commits the naturalistic fallacy, argued G.E. Moore (1873-1958) in 1903. The naturalistic fallacy is committed by those ethical theorists who profess to define good as a property of nature or as any other property than its own simple self. According to philosopher Moore, the good is a simple, indefinable concept. It is not composed of other nonmoral parts. The good exists for its own sake, argued Moore; it is not a property of something else. It cannot be defined naturalistically, or metaphysically for that matter (Moore, 1903, 1959). Observing the natural realm through scientific glasses does not reveal the good to us.

What has become a corollary is Hume’s Hurdle: one cannot draw an ought from an is. David Hume (1711-1776) had noticed with chagrin how descriptions of ‘what is’ frequently come loaded with ‘what ought to be’. The value judgment regarding what ought to be, said Hume, lies in the mind of the viewer and not the state of affairs being viewed. The goodness we perceive is not a quality of the object we perceive but rather, like a color, it is a value we paint on to it (Hume, 1888, III:iii, 469). We dare not derive a moral ought from an objective is.

“If Hume and Moore are right, it is not possible to derive normative percepts from scientific observations,” writes Ulrik B. Nissen. “Objective findings have no bearing on the questions of what one ought to do. The theory of evolution has no implication for ethics” (Nisson, 598).

Because of the naturalistic fallacy, neither the lone wolf nor the wolf pack models pass the philosophical smell test.

Roman Catholic Natural Law Theory

Roman Catholic natural law theory passes the philosophical smell test. No naturalistic fallacy here. Even though the good is embedded in nature, it comes from God.

Roman Catholic bioethicist Stephen Pope, operating from the wolf and lamb model, thinks we should open those windows to transcendence before constructing a naturalistic ethic. “Christian love requires response to needy others beyond as well as inside the circle of family, friends, and fellow believers” (Pope, 2007, 243). Wolf pack ethics gets us to in-group altruism, to be sure; but Pope wants more. He wants universal love in the service of the common good.

Must Professor Pope defy nature? Or, can he appeal to a higher nature? Pope appeals to natural law. Natural law was put into nature not by evolution, but by God. At a level deeper than nature’s law that is blood “red in tooth and claw,” Pope finds a divine law guiding us to neighbor-love. This law is natural, but it has a supra-natural source.

So, Pope wants more than merely to defy nature. For Pope, natural law provides a transcendent and healing ground for the laws of nature exhibited in a scientific assessment of the evolutionary process. “Evolutionary psychology and sociobiology give us no reason why we should be concerned for non-kin and non-reciprocators, but natural-law ethics argues that our human dignity grounds the virtues and duties of love, justice, and solidarity…we can transcend the evolutionists’ blind spots, fatalism, and reductionism and develop a more credible and morally appealing vision of humanity” (Pope, 2007, 290-291). This Roman Catholic version of the wolf and lamb model attempts to provide moral leverage not through defiance against nature but through listening to the call of a higher nature.

Jack London’s Buck listened to the call of the wild. Stephen Pope listens to the call to love.

Appeal to Special Revelation

If we affirm that nature has windows open to what transcends nature, the theologian must rely on special revelation. General revelation is not enough.

The good news is that general revelation—sometimes called ‘natural revelation’–provides a three-way bridge between Christian theology, materialist naturalism, and other religious traditions.

NRS Romans 1:20: “Ever since the creation of the world God’s eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he has made.”

Whether recognized or not, God has been prompting morally sensitive persons on all continents to observe the Golden Rule: do to others only what you would have them do to you. A minimal and rudimentary moral norm seems almost universal to the human species. Some moral norms are reasonable, so reasonable that they may be embraced in virtually all cultural contexts. Natural law theory can rely upon general revelation.

Not all religious traditions proffer a doctrine of divine creation. But they do recognize moral responsibility. Buddhism provides an example of moral responsibility without a doctrine of creation. Buddhists see the physical world as the current state of co-dependent co-arising, pratityasamutpada. The ceaseless interaction of physical and mental processes provide the backdrop for spiritual striving, according to which human consciousness strives for enlightenment, for transcendence of the natural world. This does not look at all like biblical creation. Yet, the Golden Rule makes sense. “Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful” (Udana-Varga 5,1). “Comparing oneself to others in such terms as ‘Just as I am so are they, just as they are so am I,’ he should neither kill nor cause others to kill” (Sutta Nipata 705 ).

Now, to special revelation itself. In the New Testament Christians find God’s promise of a future kingdom of peace, justice, and love. Jesus’ Easter resurrection is the promise in the form of a proleptic anticipation of a future resurrection of the dead and the establishment of God’s everlasting new creation. Both nature and society will undergo transformation, redemption. Eschatological ethical deliberation seeks to anticipate in present activity the redeemed reality of our promised future. Such a vision of a transformed future cannot be gained either by looking at evolution’s past history or by attending to the natural law of general revelation. It requires special revelation; and it requires believers to place their faith in it.

Theistic Evolution

The vision of the renewed creation can be combined by religious thinkers with Darwinian evolutionary theory into a hybrid scheme, theistic evolution. Theistic evolution pictures “our evolving universe, in all of its temporal and spatial grandeur, as moving toward an ultimate fulfillment, a new creation in the Christ who is yet to come,” avers John Haught (Haught, 2001, 64).

According to the theistic evolutionist, God has been working through evolutionary processes all along with the eschatological vision in mind. Because it is an eschatological vision, it does not appear as an entelechy within nature. God has a purpose for nature even if scientists cannot see purpose in nature (Peters T. a., 2005, 159).

Stephen J. Pope depicts “God working in and through the evolutionary process to create, sustain, and guide all of creation, including human creatures” (Pope, 2007, 110).

Robert John Russell summarizes the expectation of the theistic evolutionist.

“In essence, life cannot be reduced completely to information processing, and eschatology cannot be merely the outcome of the routine process of nature as described by scientific cosmology. Instead, life involves emergent properties and processes which transcend the competence of the natural sciences to fully explain, and the New Creation will come about as a radical transformation of the universe by a new act of God found proleptically in the resurrection of Jesus” (Russell, 2008, 284).

Rather than try to ground ethics in a strict naturalism with windows closed to transcendence, I find a firmer foundation in a theological approach that relies upon a transcendentally grounded vision of future transformation.

Tennyson wants to look “behind the veil.” This side of the veil life is frail, even futile. Even though this side of the veil we see nature “red in tooth and claw,” the poet wants to trust that love is “Creation’s final law.” In order to see behind the veil, we need to don the lenses of transcendence. We need to see more than merely what nature reveals. Special revelation in the form of God’s promise of transformation provides a way of looking at nature within the framework of its future redemption.

Conclusions

In light of this description and analysis, it is my judgment that neither Lone Wolf Ethics nor Wolf Pack Ethics adequately ground an ethic that draws us forward for the betterment of creation and the flourishing of human life. Nature does not suffice to provide us with a vision of the good worthy of our moral striving. When we look at nature through evolutionary lenses, we see our dinner plate covered with edible meat “red in tooth and claw” and perhaps garnished with some reciprocal altruism on the side. To be nourished by such a meal is to survive, to be sure; but this is not sufficient for well being or flourishing.

The ancient Athenians reminded us that the good is what all people lack and for which they strive. We do not yet possess the good conclusively; we must still strive to realize it. “The good thus contains in itself the difference between value and being,” comments theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg. “The quest for the good, seeking what is good for human beings, still provides the best starting point for ethical investigation” (Pannenberg, 1969, 106). This gives ethical theorizing and moral striving a distinctively future cast. The good is not a product of evolution’s history but rather a future goal which enlists our moral action. The horizon of the future should provide the framework for ethical deliberation, in my judgment.

If the construction of an adequate post-Darwinian ethic is to proceed, certain pillars need to be in place to support weighty moral reasoning. We need to (1) recognize and appreciate that we human beings are fully natural; (2) reconcile ourselves that no progressive teleology is built into evolution’s past; (3) attend to the significance of contingency and emergent freedom in our evolutionary history; (4) rely upon the concept of general revelation to support inter-cultural and inter-ideological consensus; and (5) hold up a vision of a renewed natural and social world based upon special revelation, the revelation that God is promising an eschatological new creation. The reliance upon special revelation regarding the promised new creation is requisite for wolf and lamb ethics.

The eschatological vision of the Peaceable Kingdom in Isaiah 11 lures us to behave now on behalf of that vision. We strive to incarnate ahead of time that future reality. The wolf living with the lamb (Isaiah 11:6) is God’s intended creation. Our creation will be complete only when it’s redeemed. Our ethical striving for the good is directed toward God’s redeemed future.

▓

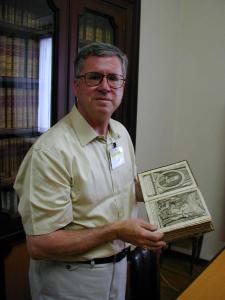

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). Along with Martinez Hewlett, he co-authored three books on the evolution controversy. Along with Martinez Hewlett, Joshua Moritz, and Robert John Russell, he co-edited, Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Intelligence (2018). Along with Octavio Chon Torres, Joseph Seckbach, and Russell Gordon, he co-edited, Astrobiology: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy (Scrivener 2021).

See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

In the near future he will publish, The Voice of Christian Public Theology with the Australian Theological Forum.

▓

References

Barnes, E. W. (1927). Should Such a Faith Offend? Sermons and Addresses. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Batson, D. (2017). The Empathy-Altruism Hypothesiis. In E. S.-T. Emma M Seppala, The Oxford Handbok on Compassion Science (pp. 27-40). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bennett, G., Hewlett, M., Peters, T., & Robert John Russell, e. (2008). The Evolution of Evil. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Bowler, P. (2007). Trials and Gorilla Sermons: Evolution and Christianity from Darwin to Intelligent Design. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Coakley, S. (2013). Evolution, Cooperation, and Ethics. Studies in Christian Ethics 26:2, 135-139.

Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selecton. London: Murray.

David, A. (2009). Our Inner Ape. UU World.

Dawkins, R. (1976, 1989). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1986). The Blind Watchmaker. London: WW Norton.

Delio, I. (2020). Theology of Nature or Relational Holism: Building on Teilhard’s Vision. In e. Ted Peters and Marie Turner, God in the Natural World: Theological Explorations in Appreciation of Denis Edwards (pp. 171-191). Adelaide: ATF.

Desmond, A. (1997). Huxley: Evolution’s High Priest. London: Michael Joseph.

Drees, W. (2003). Naturalism. In e. J Wentzel Vrede van Huyssettn, Encyclopedia of Science and Religion (pp. 593-597). New York: Macmillan, Thomson, Gale.

Edwards, D. (2020). Review of Ted Peters. In e. Anthony Kain and Hilary Regan, Denis Edwards in His Own Words (pp. 371-374). Adelaide: ATF.

Fest, J. (1975). Hitler. New York: Random House / Vintage.

Galton, F. (1892). Hereditary Genius. London:: McMillan.

Ghiselin, M. (1974). The Economy of Nature and the Evolution of Sex. Berkeley and Los Angeles CA: University of California Press.

Haeckel, E. (1905). The Wonder of Life. New York: Harper.

Haught, J. (2001). Response to 101 Questions on God and Evolution. New York: Paulist.

Hitler, A. (1925, 1971). Mein Kampf tr Ralph Manheim. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Hofstadter, R. (1944). Social Darwinism in American Thought. Boston: Beacon.

Hume, D. (1888). A Treatise on Human Nature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Huxley, T. (1880). The Coming of Age of the Origin of Species. Science 1, 15-17 + 20.

Huxley, T. (1896). Evolution and Ethics. Amherst NY: Prometheus.

Kohn, M. (11/20/2008). The Needs of the Many. Nature 7220:456, 296-299.

Løgstrup, K. (1997). The Ethical Demand. Notre Dame IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Luther, M. (2015-2020). The Freedom of a Christian. In M. Luther, The Annotated Luther, 5 Volumes (pp. 1: 467-518). Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Moltmann, J. (2003). Science and Wisdom. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Moore, G. E. (1903, 1959). Principia Ethica. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Nisson, U. (n.d.). Naturalistic Fallacy. In e. Wentzel Vrede Van Huyssteen, Encyclopedia of Science and Religion 2 Volumes.

Pannenberg, W. (1969). Theology and the Kingdom of God. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Peirce, C. S. (1931-1958). Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, 2 Volumes. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press.

Peters, T. (2nd Ed, 2003). Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom. London and New York: Routledge ISBN0-415-94248-0-415-94249-7.

Peters, T. a. (2005). Evolution from Creation to New Creation. Nashville TN: Abingdon.

Peters, T. a. (2008, 2009). Can You Believe in God and Evolution? A Guide for the Perplexed. Nashville TN: Abingdon ISBN 0-687-33551-5.

Pope, S. (2007). Evolution and Christian Ethics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Proctor, R. (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Ruse, M. (2001). Evolution. In e. Lawrence C Becker and Charlotte B Becker, Encyclopedia of Ethics (pp. 501-503). London: Routledge.

Russell, R. J. (2008). Cosmology from Alpha to Omega: The Creative Mutual Interaction of Theology and Science. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press ISBN 978-0-8006-6273-8.

Sanger, M. (1917). Birth Contol and Women’s Health. Birth Control Review 1:12.

Spencer, H. (1879). The Data of Ethics. New York: A L Burt.

Spencer, H. (1897). First Principles. New York: D Appleton.

Tillich, P. (1960). Love, Power, and Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, E. O. (1978). On Human Nature. New York: Bantam.

Wright, N. (2006). Evil and the Justice of God. London: SPCK.

Wright, R. (1994). The Moral Animal. New York: Random House.