The Wolves of Jack London

Jack London 7: “The Red One”

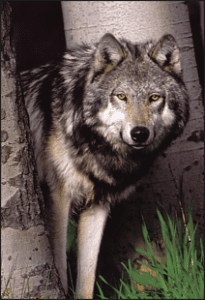

Will more highly evolved space aliens tame our wolf?

In our first three posts, we reviewed what I call “Jack London’s Wolf Troika”: The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and The Sea Wolf. In each we asked one topical question: will we Homo sapiens sapiens evolve into civilized creatures that outgrow our wolf-like tendencies toward violence? The 1916 short story, “The Red One,” gives us hope that we will.

THE WOLVES OF JACK LONDON / Jack London Society

Jack London 1: The Call of the Wild

Jack London 4: Lone Wolf Ethics

Jack London 5: Wolf Pack Ethics

Jack London 6: Wolf & Lamb Ethics

Jack London 7: “The Red One”

With the method theology-of-culture, we have been investigating the confluence of literature, science, and theology in the wolves of Jack London.

Now, as we turn to London’s 1916 short story, “The Red One,” it appears London was hoping for grace from heaven. literally from the heavens. On our own, our human species is unable to evolve fast enough or advance far enough to lose our wolf genes. Might visitors from heaven provide a celestial technology that could—by grace—lead to our transformation?

Does London mean grace from God? No. Rather, the transformation of Homo homini lupus into civilized Homo sapiens sapiens will come courtesy of advanced space alien technology. Elsewhere I’ve called this the ETI myth. London proposed this myth thirty years before the 1947 flying saucer crash at Roswell, New Mexico, which sparked the UFO era—might we say “ufocene” epoch?—we are now in.

Will more highly evolved extraterrestrials surpass the wolf?

When we turn from the Wolf Trilogy to “The Red One,” we are turning from the archonic to the epigenetic. The archonic worldview assumes that our essence is found in our past, especially in our origin. The archonic assumption dominates London’s anthropology as well as dogology. Our deep evolutionary past continues to influence if not define the present at a preconscious or even mystical level.

But, what about the epigenetic future? Epigenesis is a compound noun built on epi meaning upon or after. Epi is added to genesis meaning origin or, in our epoch, gene. In evolutionary biology, epigenesis refers to the emergence of new and more complex species. Could future evolution lead to an escape from the determinism of the past? This brings us to the ETI (extraterrestrial intelligence) myth.

Did Jack London purvey the ETI myth? Yes, I believe he did, in at least a rudimentary way. One of London’s stories, “The Red One” published in May 1916, anticipates Stanley Kubrick’s movie, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” by 52 years and Erich von Däniken’s bestselling book on ancient aliens, Chariots of the Gods?, by 56 years. And with an eerily common theme.

The Plot of “The Red One”

Through one character in the short story, a scientist named Bassett, London surmised that more highly evolved extraterrestrial intelligent beings have already advanced scientifically, technologically, and even morally. If ETI would come to earth, they would offer the human race a quantum leap into a holistic if not salvific future. This is the ETI myth in nascent form.

An English naturalist, Bassett, searches for a rare butterfly on Guadalcanal, one of the South Pacific’s Solomon Islands. The so-called civilized man penetrates the island jungle where he is attacked by head-hunting cannibals. Sick from insect bites and weak, Bassett is captured and taken to the village. A curious romance develops between the white Bassett and what he deems an ape-like woman of the tribe, Balatta.

An English naturalist, Bassett, searches for a rare butterfly on Guadalcanal, one of the South Pacific’s Solomon Islands. The so-called civilized man penetrates the island jungle where he is attacked by head-hunting cannibals. Sick from insect bites and weak, Bassett is captured and taken to the village. A curious romance develops between the white Bassett and what he deems an ape-like woman of the tribe, Balatta.

The mystery that drives the plot begins with an unidentified noise that peaks Bassett’s curiosity. The persistent sound, he is told, comes from the god of the tribe, “the Red One.” Recognizing that his own death is nigh, Bassett promises to allow his head to be taken by the tribal shaman, named Ngurn. As an exchange, he persuades Ngurn along with Balatta to satisfy his curiosity by taking him to see the Red One.

The Red One turns out to be a ball, two hundred feet in diameter, made of iridescent cherry-red metal with a pearl-like surface. The Red One is located in a pit. Surrounding it is strewn bones and skeletons of beheaded and sacrificed humans. Is the Red One apparently blood thirsty. Or, have the primitive Homo sapiens misunderstood their god?

Bassett concludes that the Red One is an artificial construction sent to Earth from outer space. Because it obviously represents an advanced technology, it has been misunderstood as divine by those practicing blood sacrifice.

Did Jack London anticipate what Ancient Alien television documentaries would be saying a century later? [See my critique of Ancient Aliens in “How to become an Astrotheologian.”]

In his insightful essay in The Call 33:1 (Spring/Summer 2022), “Comparison and Uses of the Monolith Motif in Jack London’s ‘The Red One’ (1918) and Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: Space Odyssey’ (1968), Richard Rocco provides a history of the fiction suggesting that ancient aliens influenced the evolution of Homo sapiens on Earth. In the half century between London and Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke built a bridge. I would like to extend that bridge. I suggest that what we have here is a prototype of what in our 21st century we see as the ETI myth.

Ancient Aliens, UFOs, and the ETI Myth

What is the ETI myth? (Peters 2/2009). Let me explain. The ETI myth is a conceptual set. It functions as a presupposed if not invisible framework or model for theorizing. The ETI myth provides a filter through which both UFO aficionados and astrobiologists interpret thoughts about extraterrestrial intelligence.

How does it work? This contemporary myth is premised on the false assumption that biological evolution looks like technological progress. Once this assumption is made, then the human imagination projects a phantasmagoric array of desirable evolutionary futures.

How does it work? This contemporary myth is premised on the false assumption that biological evolution looks like technological progress. Once this assumption is made, then the human imagination projects a phantasmagoric array of desirable evolutionary futures.

The ETI Myth takes the form of a projection of our terrestrial faith in progress to imaginary extraterrestrial sites. This belief in progress is a mutated variant of scientism and materialism. Here, the doctrine of progress is a secularized belief in divine providence pounded into the theory of evolution without remainder so that biological history is now guided by entelechy, direction, and purpose. The doctrine of progress puts evolution’s history and future on autopilot.

Please be clear: progressive evolution is an extra-scientific ideology. It is not sound science. Why? Because scientific methodology routinely if not universally excludes teleology at the level of assumption. The world’s leading evolutionary biologists decry any direction to evolutionary development. But space scientists still try to sneak progress in under the tent flap.

The ETI Myth is not a story like those narrated by ancient myths of origin. Rather, the ETI Myth is a set of conceptual subsets that draw conclusions from a single premise: evolution is progressive. Space scientists have a special affection for the term, advance, which indicates that progress leads to something ever more superior. Here in outline are the hidden doctrines that make up the ETI Myth.

Evolution progresses from the simple to the complex.

Complex life evolves into intelligence over time.

Intelligence leads to science and technology.

Evolving life on exoplanets has progressed longer than it has on earth.

Therefore, ETI is more advanced than we on earth.

The ETI myth exports via imagination the terrestrial progress myth to extraterrestrial civilizations. “Myth of human progress…an overarching story in which human history is pictured as a march towards Utopia, a state of moral perfection both for the society and individual” (Williams, Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1902-1907. 2021). To us the myth of progress promises redemption from scarcity, drudgery, strife, disease, and for transhumanists even death. Science saves. And, if science has millions of years to evolve, it’s salvation will be wondrous. So goes the myth of progress. The ETI myth simply tacks ETI onto the myth of progress.

Because these dreamt of extraterrestrials have evolved millions of years longer than we have, we can imagine extraterrestrials as utopian beings ready to heal all of earth’s ills. In short, the ETI myth provides a doctrine of salvation dressed in a scientific disguise. Or, to say it another way, the method of the theologian of literature is to uncover within secular myths the dimension of ultimacy. The myth of progress provides scientific clothing to hide our religious impulse.

Ancient Myth versus Modern Myth

The ancient creation myths of Ptah and Osiris functioned to provide religious justification for the power of the Pharoah on Egypt’s throne. The ancient Babylonian myth, Enuma elish, functioned to justify the power of the emperor on the throne. Does the ETI myth justify a throne? Yes, but subtly. The ETI myth functions to support the kingship of the scientist in our terrestrial society. After all, those extraterrestrials have allegedly evolved to a higher level of science and technology. This implies that we who are backward must trust our scientists to lead us forward. Here’s the problem Jack London could warn us about: today’s scientists, realistically speaking, are only wolves wearing white lab coats.

How could Jack London believe in the ETI myth if he lived a half century before the space age? Perhaps he was intuitively prescient. Perhaps he simply drew out the implications of doctrinaire evolutionism and the utopian visions associated with progress.

The Red One

Let’s look again at this 1916 short story. The craft shows signs of perfection in technology. Does it equally represent an advance in religion or morality? Does the craft anticipate our own future? I suggest that the red spacecraft represents our earthly future coming from space to speed up our evolution.

“Mellow it was with preciousness of all sounding metals. Archangels spoke in it; it was magnificently beautiful before all other sounds; it was invested with the intelligence of supermen of planets of other suns; it was the voice of God, seducing and commanding to be heard. And–the everlasting miracle of that interstellar metal! Bassett, with his own eyes, saw colour and colours transform into sound till the whole visible surface of the vast sphere was a-crawl and titillant and vaporous with what he could not tell was colour or was sound. In that moment the interstices of matter were his, and the interfusings and intermating transfusings of matter and force.” (The Red One)

In his insightful analysis of London, Lawrence Berkove notes even more subtle signs of religious depth. He calls our attention to the pearl allusion. “The kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchantman, seeking goodly pearls,” says Jesus. The merchantman, when he “found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had, and bought it” (Matthew 13:45). Berkove observes, “The reference to eternal life is the apparent meaning, but the allusion makes more sense if read ironically, because what Bassett actually buys is death” (Berkove, The Myth of Hope in Jack London’s “The Red One” 1996, 211). It’s irony that eternal life must be bought with death.

Yet, Berkove sees this story as a myth of hope. The Red One is a symbol of hope because it is the manufacture of advanced intelligences somewhere in space. “The Red One, though fearsome, may contain hope for man. But it is never opened, and its secret remains sealed” (Berkove, The Myth of Hope in Jack London’s “The Red One” 1996, 213).

Might there be two things going on here? First, the oval Red One exhibits attributes of divinity. Second, as a technological artifact that exhibits perfection, it represents our evolutionary future. Might scientific progress be inviting Homo sapiens sapiens to a socialist future that transcends our wolf past?

On the one hand, London looks backward archonically to show that our brutal pre-human or wolf-like past is still with us. At any moment, civilization can devolve–revert–into the viciousness of the wolf. On the other hand, evolution is progressive. If evolution progresses long enough and if we advance far enough, future humanoids will jettison the wolf past and emerge in the form of biological angels. London represents a precursor to today’s ETI myth shared by ufologists and astrobiologists.

The Danger of Utopian Socialism

Jack London died before witnessing how the 1918 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia introduced its own reversion to wolf-like barbarism. A plaque to Jack London is fastened to the Kremlin Wall. Joseph Stalin renamed a Russian lake after the American author.

But, London did not observe the Marxist-Leninist version of socialism when it established a Siberian Gulag Archipelago in which workers were worked to their deaths. London did not watch the rise of National Socialism in Germany, where Nazis exterminated perhaps six million citizens locally while precipitating a world war that left fifty million casualties. London did not survey the Chinese landscape where Maoist socialists put to death tens of millions of political dissidents and religious adherents.

Had London lived to see what destruction utopianism wreaks, he would not have energized his hope for a better future through political and economic revolution. Rather, he would have felt his primeval wolf hypothesis was being confirmed.

Like Buck in Alaska, historical socialism has demonstrated an unimagined capacity to kill with its own teeth and wash its muzzle to the eyes in warm blood. If Darwin and Spencer obtain here, then socialists with guns are the ones among us fit to survive. Pacifists and disciples of Jesus are slated for extinction.

Public theologians know socialist ideology is one of many brands of utopianism. Utopianism is bloody. Why? Despite the socialist vision of a future egalitarian society, socialist doctrine fails to recognize that the human race needs divine redemption. An unredeemed humanity—a humanity with the wolf still lurking within—can only behave wolflike in the future. What is needed is a level of realism that London almost surrendered on behalf of his socialist ideal.

Here is theologian Reinhold Niebuhr writing at the point where the United States has finally entered World War II in both the Pacific and European theaters.

The utopian illusions and sentimental aberrations of modern liberal culture are really all derived from the basic error of negating the fact of original sin….[This error] betrays modern men to equate the goodness of men with the virtue of their various schemes for social justice and international peace. When these schemes fail of realization or are realized only after tragic conflicts, modern men either turn from utopianism to disillusionment and despair, or they seek to place the onus of their failure upon some particular social group or upon some particular form of economic and social organization. (Niebuhr 1941, 1: 273)

I believe it’s safe to say that Jack London had accurately identified original sin, even though he used different vocabulary. He found it in reversion to wolf-likeness. London was realistic on this count. Yet, his vision of socialism along with his vision of more highly evolved extraterrestrials stopped short of promising redemption.

Finally, it’s about Hope

Finally, it’s about Hope

Grounding our ethics in evolutionary nature alone leaves us without hope. Why? Because, according to any ethical naturalism, we’re determined by our past. To hope, we need reason to expect a different future. God has promised a redeemed future. But we require special revelation to warrant hope in that future. That revelation comes in oblique ways. A space ship visiting us from an off-Earth planet might be one way. Perceiving resurrection within crucifixion might be another way. Tara Isabella Burton, writing in the Hedgehog Review, “On Hope and Holy Fools,” makes this point when explicating Book V in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov.

“There is nothing very sexy about hope. Certainly, there is nothing sexy about grace. The idea that we might be redeemed by an act of love—a wordless affirmation of something beyond the paradigms through which we are capable of understanding ourselves—is, well, a little mawkish, a bit cringe. Hope has little aesthetic appeal. Hope is the awkward comic reversal, shoehorned in.”

London shoehorned hope in via a UFO. Christians shoehorn in both hope and grace via the cross and resurrection.

Conclusion

“I am deeply interested in all the questions that stir humanity,” London told a reporter in 1905. But, what are the answers to those stirring questions? Descriptive answers can be found in the past. Prescriptive answers—answers that lead to transformation–require the future.

Scientifically, London was a determinist if not a fatalist. Darwinian evolutionary theory bequeathed to contemporary humanity a dark spot that could not be cleansed by the soap of civilization. Our propensity to uncontrollable violence lurks perpetually below the surface of civil order. Yet, because science is progressive, London could have speculated that perhaps human morality might be progressive as well. Might we be able to evolve ourselves to a redemptive future?

For the theologian, only God’s grace can fully transform a fallen creation. God offers us that grace in, with, and under the evolutionary process and within human history.[1] God offers that grace each moment when we perceive a possibility for a different future, when the new beckons us to depart from the old. Tomorrow’s virtues need not repeat yesterday’s sins.

Finally, it is my judgment that we ought not blame our beastly ancestry for today’s ethnic rivalries, competition for natural resources, stock market subterfuge, or international threats. News media snarling or bare-fanged political growling is largely the result of choice, not destiny. Each generation is confronted with an open future, with possibilities for transformation. The future need not be what the past was. Yesterday’s wolf need not provide the exhaustive explanation for today’s civilization let alone tomorrow’s hope.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching theology and ethics. He specializes in the creative mutual interaction between science and theology. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and Patheos column on Public Theology, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] Ralph C. Wood, who teaches Theology and Literature at Baylor University, recall, carefully interprets both Pope Benedict XVI and fiction writer Flannery O’Conner. He concludes that “the natural order is never autonomous but always and already graced” (Wood, Flannery O’Conner, Benedict XVI, and the Divine Eros 2010).References

Basket, Sam. 1996. “Sea Change in The Sea Wolf.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassato and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 92-109. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Berkove, Lawrence. 2004. “Jack London and Evolution: From Spencer to Huxley.” American Literary Realism 36:3 243-255.

Berkove, Lawrence. 1996. “The Myth of Hope in Jack London’s “The Red One”.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassuto and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 204-216. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Brandt, Kenneth. 2018. “Jack London: An Adventurous Mind.” In Jack London, by Kenneth K. Brandt. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press (Northcote).

Brooks, David. 2019. The Second Mountain. New York: Random House.

Deudney, Daniel. 2020. Dark Skies: Space Expansionism, Planetary Geopolitics, and the Ends of Humanity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, James. 1978. “A New Reading of The Sea Wolf.” In Jack London: Essays in Criticism, by ed Ray Wilson Ownbey, 92-99. Santa Barbara CA: Peregrine Smith.

Faulstick, Dustin. 2015. “The Preacher Thought as I Think.” Studies in American Naturalism 10:1 1-21.

Kean, Sam. 5/6/2011. “Red in Tooth and Claw Among the Literati.” Science 332 654-656.

Labor, Earle. 1996. “Afterword.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassuto and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 217-223. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Leder, Steve. 2019. “The Beasts Within Us.” Time Special Edition on The Science of Good and Evil 84-87.

London, Jack. 1903. The Call of the Wild.

—. 1916. The Red One.

—. 1906. The Sea Wolf.

—. 1904. White Fang.

Lundblad, Michael. 2013. The Birth of a Jungle: Animality in Progressive Era US Literature and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moritz, Joshua. 2008. “Evolutionary Evil and Dawkins’ Black Box.” In The Evolution of Evil, by Martinez J Hewlett, Ted Peters, and Robert John Russell, eds Gaymon Bennett, 143-188. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Niebuhr, Reinhold. 1941. The Nature and Destiny of Man, 2 Volumes. New York: Scribners.

Oliveri, Vinnie. 2001. “Sex, Gender, and Death in The Sea Wolf.” Pacific Coast Philology 38 99-115.

Peters, Ted. 2/2009. “Astrotheology and the ETI Myth.” Theology and Science 7:1 3-30.

Reesman, Jeanne Campbell. 2012. “The American Novel: Realism and Naturalism.” In A Companion to the American Novel, by ed Alfred Bendixen, 42-59. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Scott, Nathan. 1994. “A Ramble on a Road Taken.” Christianity and Literature 43 (2): 205-212.

Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S., et.al. 2020. “Arctic-adapted dogs emerged at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition.” Science 368:6498 1495-1499.

Stasz, Clarice. 1996. “Social Darwinism, Gender, and Humor in Adventure.” In Rereading Jack London, by eds Leonard Cassuto and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, 130-140. Stanford CA: Standord University Press.

Tillich, Paul. 1951-1963. Systematic Theology. 1st. 3 Volumes: Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilkinson, David. 2013. Science, Religion, and the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Jay. 2014. Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1893-1902. Lincoln NB: University of Nebraska Press.

—. 2021. Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London 1902-1907. Lincoln NB: University of Nebraska Press.

Wood, Ralph. 2010. “Flannery O’Conner, Benedict XVI, and the Divine Eros.” Christianity and Literature 60:1 35-64.

Wood, Ralph. 2012. “The Lady in the Torn Hair Who Looks on Gladiators in Grapple: G.K. Chesterton’s Marian Poems.” Christianity & Literature 62:1 29-55.