How To Become an Astrotheologian? SR 161

The new photos of our cosmos from the James Webb telescope are informative, scintillating, and even inspiring. So, in Dialog, A Journal of Theology, I ask: how can I become an astrotheologian? There are seven easy steps. I’ll list them below in this Patheos post. But first, what is astrotheology, anyhow?

What is Astrotheology?

Astrotheology is theological reflection on astrobiology? So, what’s astrobiology? Let’s ask Lucas Mix, project Coordinator for ECLAS (Equipping Christian Leadership in and Age of Science) at St. John’s College, Durham University, in the UK.

“Astrobiology is the scientific study of life in space. It happens when you put together what astronomy, physics, planetary science, geology, chemistry, biology, and a host of other disciplines have to say about life and try to make a single narrative” (Mix 2009, 4)

Astrobiology is an almost religious science. Why? Because outer space floods our minds with awe. The astrotheologian needs to take only baby steps to walk us from the awesomeness of the immense cosmos to the question about the God who created this cosmos.

Just how does astrotheology take us from the science of astrobiology to God? Here’s the definition I like the best.

Astrotheology is that branch of theology which provides a critical analysis of the contemporary space sciences combined with an explication of classic doctrines such as creation and Christology for the purpose of constructing a comprehensive and meaningful understanding of our human situation within an astonishingly immense cosmos (Peters 2018, 23-24, italics in original).

And, because space is public, I believe astrotheology belongs in public theology. Public theology, I say repeatedly in this Patheos column, is conceived in the church, critically honed in the academy, and offered to the wider world for the sake of the global common good. Maybe we should say: for the galactic common good.

Dialog, A Journal for Theology

In the summer 2022 issue of Dialog, A Journal of Theology, Michael Waltemathe and I have assembled a collection of articles introducing astrotheology. Michael is a theologian at Ruhr-University in Bochum, Germany, with many interests that overlap with mine. Michael specializes in discourse clarification of the social impact of computerization and social media. He also has a strong interest in astrobiology. With Paul Levinson, Michael has co-authored, Touching the Face of the Cosmos: On the Intersection of Space Travel and Religion.

What will you find in this issue of Dialog? First, astronomer José Funes, S.J., former director of the Vatican Observatory, provides an illuminating introduction to what every non-scientist needs to know in his article, “The Human Future: Space Exploration, Cooperation, and the Challenges Ahead.”

Will we earthlings settle Mars? Should we colonize off-Earth bodies in space? German theologian Christian Weidemann says, “yes,” in “Providence and the Magnitude of the Universe: a Theistic Argument for Space Settlements.”

Finally, anthropologist Margaret Boone Rappaport along with Vatican Observatory astronomer Christopher J. Corbally give us a fictional scenario of human life after we’ve settled and colonized Mars in “Religion’s Role in a Martian War of Indendence.”

How may I become an astrotheologian?

I outline the steps to become an astrotheologian in my Dialog article, “Deep grace in deep space? How to become an astrotheologian” Would you like to follow these seven easy steps? Here’s the ladder.

Before the first step: astrotheological ponderings

This year, 2022, marks the 60th anniversary of an event most of us have forgotten or ignored in the first place. In 1962 the United Nations General Assembly passed the Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space.

Now, six decades later, we’ve landed astronauts on the Moon, placed communication satellites in orbit, remotely explored Mars as well as the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, and set up radio receivers to monitor extraterrestrial signals. Civilization has space in its mind. Might the public theologian open our religious minds to the larger cosmos? It’s time to become an astrotheologian and perhaps even an astroethicist.

In previous ponderings in Patheos we have given attention to what the space sciences tell us about our glorious yet mysterious cosmos. In one post we asked whether the Copernican Principle is a scientific or cultural principle, concluding that it is neither. Elsewhere we asked the important question: would the discovery of extraterrestrial intelligence cause a crisis for terrestrial religion? Another post dealt with Lucas Mix, astrobiologist and theologian, on life in the cosmos. Similarly, we interviewed Steven Dick on “cosmotheology.” In another post we asked if NASA along with hired priests were preparing for ETI contact. In still another post we asked if alien scientists are our real gods? In this newsletter post, we climb the seven-step ladder to astrotheology. Are you ready for the first step?

- Become sensitive to the Beyond and the Intimate when talking about the true God.

Step one on the ladder to become an astrotheologian consists of meditating on God as the beyond and the intimate in light of cosmic consciousness.

There is nothing beyond God. St. Anselm gave us this handy dandy definition: “God is that than which nothing greater can be conceived” (Anselm 1077). Whether it’s the sky or deep space beyond the sky, God is beyond both what we can perceive and what we can conceive.

There is nothing beyond God. St. Anselm gave us this handy dandy definition: “God is that than which nothing greater can be conceived” (Anselm 1077). Whether it’s the sky or deep space beyond the sky, God is beyond both what we can perceive and what we can conceive.

Nor is there anything more intimate than God. St. Paul reminded us that God’s Holy Spirit lies within us at a level deeper than the self. “In the same way, the Spirit helps us in our weakness. We do not know what we ought to pray for, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us through wordless groans” (Romans 8:26). To get to the beyond, we must travel through what is most intimate.

This implies inter alia that the astrotheologian should foster cosmic consciousness within us. We need to open space in our mind as a receptor of God’s transcendence.

- Think cosmically.

If you wish to become an astrotheologian, expand the scope of your worldview beyond Earth. It is the cosmos, not merely planet Earth, that counts as God’s creation. The cosmos includes the stars. It also includes extraterrestrial creatures, if any exist.

Ask questions such as these. How does God’s grace apply (1) to inanimate physical and chemical processes located at unconquerable distances elsewhere in the universe? (2) to microbial or non-intelligent life within our solar system or elsewhere in the Milky Way galaxy? (3) to intelligent life elsewhere in the Milky Way? (4) to galaxies beyond the Milky Way are speeding away at such high rates of speed that we cannot imagine any two-way communication? Most practically, ask this question: (5) just what will aliens bring to our covered dish potlucks?

- Do not be bullied by the Cosmological Principle or the Copernican Principle.

Be bold. Do not be bullied by those cynics who try to marginalize our Earth and our species by declaring us to be so small that we’re insignificant.

To say it another way: do not let the Cosmological Principle or Copernican Principle bully you. Both anti-religious and progressive-religious forces belittle the Christian tradition for allegedly being geocentric, anthropocentric, and egocentric. These forces want us to feel small, miniscule, humble, marginal, insignificant.

The size of our universe is awesome, to be sure. Our cosmos contains perhaps one or two trillion galaxies (Conselice 2017). Even with this immensity, I say: not so fast! Don’t cower. Don’t apologize for being small. If you wish to become an astrotheologian, think this through before reacting.

According to the Cosmological Principle formulated by Edward Milne, our universe is homogenous and isotropic. Here’s the Cosmological Principle described by Harvard astronomer Owen Gingerich. The Cosmological Principle says “that the universe should be homogeneous and uniform not only in space, but also in time” (Gingerich 2014, 112). In short, we can expect the laws of nature that obtain here on Earth to obtain on every galaxy regardless of how distant.

Here’s the Copernican Principle, formulated by Herman Bondi (1919-2005) who coined the term. “This removal of the Earth from any position of great cosmological significance is generally known, even today, as the Copernican Principle. It has become a cornerstone of modern astrophysics” (Bondi 1952, 13).

These two principles are frequently used to de-center Planet Earth. They are used to demote human race to marginal status in a giant universe. Do you feel very marginalized now?

Here is what the astrotheologian brings to this conversation. Despite the size and grandeur of the cosmos, God is still mindful of us humans (Psalm 8). This fact does not change with Copernicus.

These two astrophysical principles–the Cosmological and the Copernican–look a lot like what theologians know from scripture as the Logos. The Logos is the rational structure within the trinitarian perichoresis upon which the structure of the creation is established. The divine Logos incarnate in terrestrial history in Jesus Christ is just as much at home in the Whirlpool Galaxy as it is on Earth.

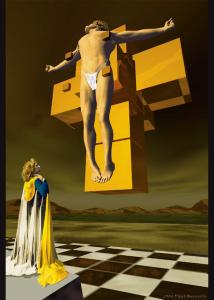

- Explore deep incarnation in deep space.

If all you can think about when you hear the word, incarnation, is a Christmas creche with the baby Jesus in a manger, then don’t become an astrotheologian. But, if you want to ask about God’s grace in outer space, then I recommend you apply deep incarnation to the galaxy if not the entire cosmos.

What’s deep incarnation? Let’s ask Copenhagen’s Niels Henrik Gregesen. When the universal Logos became incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth, “the divine Logos…has assumed not merely humanity, but the whole malleable matrix of materiality” (Gregersen 2010, 176). God’s Logos has taken up the material substance of every galaxy, every planet, every sentient being into the divine perichoresis of the Holy Trinity.

We find deep incarnationist Christology today in leading thinkers such as Elizabeth Johnson, Celia Deane-Drummond, Richard Baukham, Kristin Johnston Largen, Robert John Russell, Jamie Fowler, and the late Denis Edwards.

To date, Gregersen and other deep incarnation theologians have advanced three important points. First, the Logos (λόγος) in the flesh incorporates all physical reality into the trinitarian life of God. Second, because all physical reality is taken into the divine life, then God suffers with every creature in its own suffering. Third, this shared suffering is redemptive, at least according to the deep incarnation school of Christology. Because shared suffering is redemptive, it follows that this divine sharing resolves the theodicy problem: God is the victim of suffering, not the perpetrator.

Might we see consonance between the Cosmological Principle and Logos Christology? Drew theologian Catherine Keller connects the two. “Primal themes, like E=mc2 and the law of gravity, seem to express the law or Logos of this universe” (Keller 2008, 60). What theologians have learned from Holy Scripture about God’s Word seems consonant with the Cosmological Principle, with the confirmed assumption that the most distant galaxies operate according to the same principles we see exhibited here on Earth.

So, to become an astrotheologian with the Logos in mind, you should ask this question: how can we conceive of the redemptive efficacy of deep incarnation on a cosmic scale?. Redemption makes us think of eschatology, of new creation. How broad is the scope of eschatological redemption? Is redemption just as cosmic as creation?

- Add eschatology to deep incarnation.

Deep incarnation needs eschatology for it to be redemptive. In the case of astrotheology, there is more than merely enunciating nice words at funerals. Eschatology is cosmically inclusive. Andreas Losch believes “theology can remind science that the completeness of knowledge is of an eschatological nature” (Losch 2017, 208).

Redemption is achieved through the Easter resurrection followed by the eschatological new creation. Or, perhaps it’s the reverse. God’s future new creation reaches back into our temporal span and blesses us with that redemption in anticipation. In sum, the public theologian now an astrotheologian becomes an eschatological theologian, applying God’s promises to our cosmic future.

- By using a Theology of Culture, demarcate science, scientism, and pseudoscience.

If you wish to become an astrotheologian, then observe how space is already present in many minds. Only some minds are scientific. All are cultural. Within culture, we find criticisms of the space sciences for colonial hegemony. The astrotheologian like every public theologian should hone the insights of a theology of culture that takes culture’s internal self-critiques into account.

If you want to become an astrotheologian, embrace science but shun scientism. Scientism is the materialist ideology that sometimes covers the face of science like a ski mask hides a down-hiller’s identity during a slalom. Genuine science provides genuine knowledge. Celebrate this knowledge.

But, beware of scientism. Michael Waltemathe shows how “the political system and the science system are leading up society’s coping roles. ‘Science saves’, is the repeated message,” especially in our Covid era (Waltemathe 2020, 204). In short, the theologian’s eyes should discriminate between the mask and the skier.

Of additional interest to the astrotheologian is pseudoscience and the demarcation problem. In The Demarcation Problem, we ask: how do we “distinguish science from pseudoscience” (Gordin 2015, 219). Drawing the demarcation is difficult because many pseudoscientists genuinely believe in their science. It becomes even more difficult when elements of genuine science are blended with scientism, wishful thinking, fantasy, and a large public following. My only advice to the struggling astrotheologian: do the best you can.

Today the Demarcation Problem arises for the astrotheologian on two fronts, the popularity of the Ancient Astronaut television series and the UFO phenomenon.

The notionate Ancient Astronaut theory to re-explain ancient artifacts is pure fantasy without any saving scientific grace. Yet the idea of ancient alien influence on Earth is purveyed in a most attractive and exciting medium that elicits within us a response: this is reality. But, according to the Smithsonian Magazine, it’s a hoax.

The UFO phenomenon is much more subtle than the ancient alien fantasy. It would be disingenuous for the public theologian to dispute categorically the claims of so many contemporary experiencers of daylight disks, fly-by-nights, physical traces such as radar tracking, and close encounters of the first, second, and third kind. As a UFO investigator myself, I have interviewed these experiencers and judged many of them to be utterly sincere in believing what they report.

The UFO phenomenon is much more subtle than the ancient alien fantasy. It would be disingenuous for the public theologian to dispute categorically the claims of so many contemporary experiencers of daylight disks, fly-by-nights, physical traces such as radar tracking, and close encounters of the first, second, and third kind. As a UFO investigator myself, I have interviewed these experiencers and judged many of them to be utterly sincere in believing what they report.

The religious dimensions to the UFO phenomenon should be obvious to any theologian of culture. Yet, there is a strong scientific component to the UFO phenomenon when viewed in its comprehensive form. The most active research organization, the Mutual UFO Network or MUFON, understands itself as employing the “scientific method.” One goal is this: “Promote research on UFOs to discover the true nature of the phenomenon, with an eye towards scientific breakthroughs, and improving life on our planet.”

Pondering the theological implications of alien visitors piloting UFOs can be challenging. On the one hand, if we assume that extraterrestrial intelligent creatures evolved on exoplanets, then we tacitly affirm Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and disavow creationism. On the other hand, if we posit that ETI are spiritual rather than physical beings, then we rely on an outdated metaphysics. Anthony Costello, a Patheos columnist in “Atheists, UFOs, and the Bible,” opts for the second alternative. “They [extraterrestrial beings visiting Earth in UFOs] are not material beings that evolved through secondary causal processes, as we imagine aliens like E.T. would be. They are spirits and, being spirits, have been with us from the very beginning.” How should we adjudicate such options?

When pondering both ancient astronaut theory and the UFO phenomenon, at least for the time being, I heartily recommend that the astrotheologian ally with established astrobiologists and other scientists who demand research rigor. Consider joining SCU (Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies).

- Contribute to Astroethics

Step seven to become an astrotheologian adds engagement in astroethics. The astroethicist needs to engage in discourse clarification regarding the prospects of space exploration, settling other planets, and encountering extraterrestrial life. A good place to begin is to remind ourselves of what was said in the 1962 the United Nations General Assembly’s Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space. The first three principles will be of interest to progressives everywhere.

- The exploration and use of outer space shall be carried on for the benefit and in the interests of all mankind.

- Outer space and celestial bodies are free for exploration and use by all states on a basis of equality and in accordance with international law.

- Outer space and celestial bodies are not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

The UN makes it clear that the Moon and other celestial bodies are not to be treated as another Wild West with claims, counterclaims, and shoot-outs. The “benefit” of space exploration is to accrue to the “interests” of the entire human race regardless of nationality. When engaging in discourse clarification, the astrotheologian can make transparent the widespread intuitive assumption that off-Earth real estate should not become the private property of billionaires or the launching pad for nuclear warheads.

Scholar Mary-Jane Rubenstein is monitoring the threat to the sacrality of outer space by the private sector. See her book: Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race. Rubenstein along with Lance Gharavi are conducting a series of webinars, “Sacred Space: Religion and Cosmic Exploration Symposium–What is the cosmic future of humanity?”

Elsewhere, I draw a roadmap for an Astroethics of the Galactic Common Good. I recommend that we begin caring for space neighbors we have yet to meet. Here is a mere list of concerns that may soon migrate on to the astroethicist’s agenda.

Astrotheology as Public Theology

Patheos is already online public theology at work.

At Patheos, we believe faith is a force for good in the world, but we also know it’s hard to find accurate information about religion online. We exist to help provide information, stories and conversation that leads to understanding, empathy and acceptance of all faiths.

The astrotheologian is a public theologian too. Oh yes, the plate of the public theologian is filled with many delicacies in addition to space. Yet, an ample portion of space should be included in the public theologian’s fare.

I think of public theology as conceived in the church, critically reformulated in the academy, and meshed with the wider culture for the sake of the global common good. Or, the galactic common good. This suggests, among other things, that the astrotheologian and astroethicist offer wisdom and sound judgment to the public policy making sectors of our wider society.

Will Christians find non-Christian partners in pursuit of the global and galactic common good? Quite likely. A movement marching under the banner of “Exotheology” is showing life within international Islam. Here’s Layla Azmi Goushey at St. Louis Community College reporting with optimism, “Islamic Exotheology: Viewpoints on Extraterrestrial Intelligence.”

“Just as Muslims have always pursued science to see what God instilled in creation, we are now in a new phase of an Islamic intellectual awakening along with other theologies and cultures around the world. Space exploration by the United Arab Emirates and other countries will provide new opportunities for scientific discovery and will deepen our ‘Ilm, or knowledge, of the limitless wonder of the universe.”

Conclusion

God loves the cosmos, we are told in John 3:16. Perhaps the astrotheologian could love it too. Certainly Russian Orthodox physicist, Alexei Nesteruk, would concur. “To enquire into the sense of the universe means not only to know it, but to be in communion with it, to love it” (Nesteruk 2015, 6).

▓

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). Along with Martinez Hewlett, Joshua Moritz, and Robert John Russell, he co-edited, Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Intelligence (2018). Along with Octavio Chon Torres, Joseph Seckbach, and Russell Gordon, he co-edited, Astrobiology: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy (Scrivener 2021). He is also author of UFOs: God’s Chariots? Spirituality, Ancient Aliens, and Religious Yearnings in the Age of Extraterrestrials (Career Press New Page Books, 2014). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters directs traffic at the intersection of science, religion, and ethics. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. He authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). Along with Martinez Hewlett, Joshua Moritz, and Robert John Russell, he co-edited, Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Intelligence (2018). Along with Octavio Chon Torres, Joseph Seckbach, and Russell Gordon, he co-edited, Astrobiology: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy (Scrivener 2021). He is also author of UFOs: God’s Chariots? Spirituality, Ancient Aliens, and Religious Yearnings in the Age of Extraterrestrials (Career Press New Page Books, 2014). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Here’s a VIDEO: “Will Ufologists and Astrobiologists Dine at the Same BBQs?”

▓

References

Anselm. 1077. Prosologion. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-classicreadings/chapter/st-anselm-on-the-ontological-proof-of-gods-existence/.

Bondi, Herman. 1952. Cosmology. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Conselice, Christopher. 2017. “Our trillion-galaxy universe.” Astronomy 45:6 8.

Gingerich, Owen. 2014. God’s Planet. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Gordin, Michael. 2015. “Myth 27: That a Clear Line of Demarcation Has Separated Science from Pseucoscience.” In Newton’s Apple and Other Myths about Science, by eds Ronald L Numbers and Kostas Kampourakis, 219-225. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Gregersen, Niels Henrik. 2010. “Deep Incarnation: Why Evolutionary Continuity Matters in Christology.” Toronto Journal of Theology 26:2 173-187.

Keller, Catherine. 2008. On the Mystery: Discerning God in Process. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Losch, Andreas. 2017. “What Theology Can Contribute to the Question: What Is Life?” In What is Life? On Earth and Beyond, by ed Andreas Losch, 201-212. Camnbridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mix, Lucas J. 2009. Life in Space: Astrobiology for Everyone. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Nesteruk, Alexei. 2015. The Sense of the Universe. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Peters, Ted. 2018. “Introducing Astrotheology.” In Astrotheology: Science and Theology Meet Extraterrestrial Life, by Martinez Hewlett, Joshua M. Moritz, and Robert John Russell, eds. Ted Peters, 3-26. Eugene OR: Cascade Books.

Rubenstein, Mary-Jane, 2022. Astrotopia: The Dangerous Religion of the Corporate Space Race. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Waltemathe, Michael. 2020. “Contingency and changing reality: Perspectives from Germany.” Dialog 59 201-205.