According to a recent CBS News poll, two-thirds of Americans now think that there is intelligent life on other planets, up from 47% in 2010. Moreover, 70% of those believers in extraterrestrial life think that unidentified flying objects like those much in the news lately might be visiting aliens. (“U.S. Finds No Evidence of Alien Technology in Flying Objects,” read a New York Times headline last week, “but Can’t Rule It Out, Either.”)

Christians have actually contemplated the possibility of life in the heavens for a long time. As Tal reported here in 2018, extraterrestrial life “was a lively topic in the Middle Ages,” particularly during the 13th century, when scholastic thinkers debated the possibility and its implications and the bishop of Paris insisted that God could create multiple life-bearing worlds. (It’s behind a paywall, but The National Review just ran a similar article about the Early Church.) More recently, in the wake of the last big UFO hullabaloo, BioLogos president Deb Haarsma wasn’t convinced that (intelligent) life exists beyond Earth, but she also wasn’t bothered by the prospect:

Scripture shows that God is generous, even extravagant, in creating an Earth that is fruitful in producing many life forms. This can be extended to say that God has created a fruitful universe with many intelligent beings. Yet that wouldn’t diminish God’s love for us—just as God loves each individual, God has the capacity to love each species in a special way.

Indeed, she was dismayed that “most speculation about intelligent aliens leaves out God entirely.”

I’m not sure this is actually true. Perhaps she’s right that science fiction tends to be disinterested in religion (though Philip once wrote about a counterexample to that claim), but there are plenty of people who make religious meaning of alien life. They just don’t necessarily reside within the boundaries of orthodox Christianity.

I’ll leave it to John to write about other worlds in Mormonism, and UFO religions like Raëlism and the Heaven’s Gate cult seem right up Philip’s alley. And I’m not the one to write about Emanuel Swedenborg’s 1758 book, Life on Other Planets. But I can contribute one, still more obscure example, since he happens to make a cameo in my next book.

In late 1936, early in his family’s three-year exile in Europe, Charles Lindbergh befriended a former British army officer named Sir Francis Younghusband. One of the most famous explorers of the day, Younghusband had surveyed the Himalayas and served as president of the Royal Geographical Society. But while leading an expedition to — or, invasion of — Tibet in 1903-1904, he had a mystical experience that sparked a turn toward pantheism and theosophy and deepened his fascination with Eastern religions. When he met Lindbergh, Younghusband not only encouraged the pilot’s interest in hypnosis and fire-walking but talked Lindbergh into joining him in March 1937 at a world parliament of religions, held in Calcutta in honor of the Hindu mystic Ramakrishna.

Younghusband’s most remarkable religious conviction wasn’t centered on South Asia, however, but on a planet circling the star Altair.

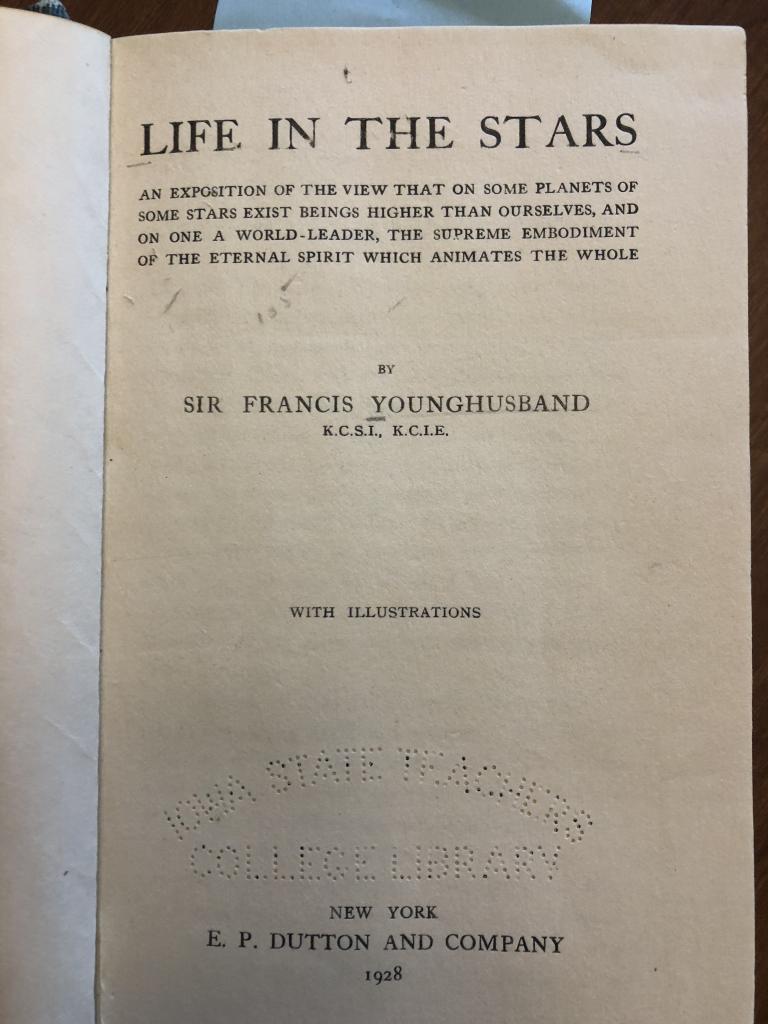

In April 1927, one month before Charles Lindbergh made his famous flight to Paris, Younghusband completed a new book, Life in the Stars. “On the wings of well-controlled imagination,” he began, “we must speed through the heavens” and contemplate “the inhabitability of the stars.” Based on his reading of and conversations with astronomers and biologists, he found the possibility of extraterrestrial life likely — at least, no more unlikely than his own existence had seemed to the mountain-bound Himalayan peoples who hadn’t encountered a European until he reached them. Sheer probability suggested to him that “some of these thousands of millions of stars must have planets as the sun has… on some of these planets there must be life of some kind… some of this life may be higher than our own.”

But for all Younghusband’s attempts to use science to control his speculation, it was philosophy, poetry, and especially religion that fired his imagination. After all, he explained, “it is often through religious feeling that the first inkling is obtained of some great universal truth,” such as “divine being or beings dwelling in the heavens.” Raised by a devoutly evangelical mother, Younghusband first appealed to “our own religion” for inklings of life beyond Earth, drawing on the Old and New Testaments, the Book of Common Prayer, and Christian hymnody to find “fervent expression… given to the idea of God and angels dwelling in heaven and influencing us from above.” Putting this idea together with the insights of science and philosophy, Younghusband concluded that the “heavenly beings”of Christianity had to be “actual, tangible, visible, living beings dwelling on the planets of the stars…. Their forms might be altogether different from ours or anything on this earth. But the spirit which animated them would be precisely the same.”

On one particular planet orbiting one “supreme star,” Younghusband imagined a “World-Leader” among the star-dwellers: “the completest and most perfect expression of the nature of the Whole, [he] would make manifest in the fullest manner, and in the highest degree, what is in the heart and soul of the world.” (Six years later, in The Living Universe, Younghusband decided that the planet in question orbited the star Altair, whose denizens were the highest of the heavenly beings.)

Though the Leader would be mostly beyond human imagining, Younghusband described him in Christ-like terms. Having withstood “the most seductive temptations” and been “made perfect by suffering,” the Leader “would be of an awful purity and unutterably holy. He would be Holiness itself made manifest; the very embodiment of the Holy Spirit of the World: a hallowed Presence in which all would bend the knee.” At the same time, he would embody “a redeeming love which would thoroughly purge and transfigure, and be of a sweetness none could resist.”

And just as Jesus’ story went far beyond its beginning to reach most of our sun’s third planet, the Leader “would not be satisfied with only influencing his own star. He would want his influence to extend over the whole universe.” For Younghusband, this then explained mystical experience on Earth: from the Magi pondering the star over Bethlehem to Wordsworth recognizing in nature “the Soul of all the worlds” to the more transcendent religious experiences among William James’ Varieties. Christianity, then, was just one attempt to describe and interpret human glimpses of life in the heavens. “The kingdom of God is within us, it is certain” he concluded. “And we can see it if we only open ourselves to the kingdom of God which is above us. And then we shall see that the two are one—that heaven is in us and we are in heaven.”

Life in the Stars was popular enough to enter a second edition in 1928, but Younghusband’s ideas didn’t catch on. When he died in 1942, after suffering a stroke while he spoke to another gathering of world religions, obituaries emphasized his achievements as a soldier and explorer. Even the Manchester Guardian, which called him a “proconsul who had become a prophet” on account of his interreligious work, politely said nothing about Younghusband’s speculations regarding extraterrestrial life.

But perhaps he was simply ahead of his time. In her 2019 book, American Cosmic, University of North Carolina religion professor Diana Pasulka reported on belief in UFOs and aliens. Some of her subjects were “scientist-believers” who treat UFO reports as empirical verification of reasonable speculation about nonhuman intelligence. One of them told Pasulka he couldn’t understand why “ufology” was associated with religion. “[T]he history of religion,” she explained, “is, among other things, a record of perceived contact with supernatural beings, many of which descend from the skies as beings of light, on light, or amid light.” Such “contact events” spawn interpretations, then interpretive communities — mostly online, in the case of UFO religions — and then religious institutions.

In 1927 Francis Younghusband predicted that human fascination with nonhuman, heavenly beings would lead to churches giving way to “more truly spiritual societies,” whose members would more fully experience the “World-Love” emanating from the World-Leader. It didn’t happen in the twentieth century; time will tell in the twenty-first.