ST 4120. Afterlife 10. Looking ahead to Easter and Beyond.

Resurrection of the Body

The gospel message of resurrection should give us comfort in the face of the premature death of a loved one or even as we anticipate our own final destiny. But, this beautiful message has been eviscerated by our pastors. Well, this is the complaint Patheos columnist Frederick Schmidt, “Why insist on the Resurrection?”

“There are lots of reasons for that. Part of the blame lies with seminary educations. Far too many clergy are shaped early on by academics, who themselves, don’t really believe in the Resurrection. Far too occupied with being academically credible, they reinterpret or drop the Resurrection from their vocabulary, hoping to gain respectability in the larger academic community where subjects like the Resurrection are considered children’s stories…. Garbage in, garbage out, garbage from the pulpit.

Another reason that people are stripped of confidence in the promise of the Resurrection is the materialist orientation of our culture. What we believe is real, is what we can hear, see, smell, taste, and touch – what we can measure – and reduce to data points. The Resurrection, of course, doesn’t lend itself to that kind of examination, so we assume that it can’t be true.”

That is the complaint of Frederick Schmidt. Maybe others as well. Here I ask: just what is this resurrection that seminaries allegedly no longer teach? Just what is this resurrection that materialists no longer believe in?

Here it is as St. Paul explains it in 1 Corinthians 15: when God raised Jesus from the dead on the first Easter, God promised to raise you and me at the future advent of the New Creation. Like a seemingly dead seed buried in the ground, our dead body plus soul and spirit will sprout and flower into a soma pneumatikon, a spiritual body in God’s eternity. Jesus’ Easter resurrection was a prolepsis of our resurrection. That’s the Christian promise. This may be difficult to believe, but it is God’s promise.

Here in this Patheos series on the afterlife we will respond to 1 Peter 3:15: “Always be ready to make your defence to anyone who demands from you an account of the hope that is in you.” Now, let’s give that account for the hope that is within us.

Jesus’ Easter Resurrection is a Prolepsis of Our Resurrection

God’s eschatological promise symbolized by the “kingdom of God” or the “new creation” anticipates the renewal of all things. The vision of the Peacable Kingdom in Isaiah 11 where the lion and wolf will lie down with the lamb presents the natural world about which God can honestly say in Genesis 1:1-2:4a, “Behold, it is very good.” The vision of the New Jerusalem in Revelation 21 presents the healing dimension of our salvation where there will be no more

‘See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.’ (Revelation 21:3-4)

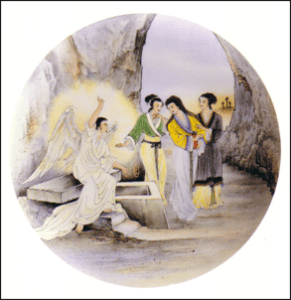

On the first Easter Sunday when God raised Jesus from the tomb, our risen Lord embodied ahead of time the Peacable Kingdom and the New Jerusalem. Jesus anticipated in his person the equivalent of resurrection for the entire creation, namely, the new creation. Jesus is the personal prolepsis of the redemption of the entire cosmos. That is the New Testament promise.

That is also the Christian hope.

Resurrection of the Body

When reciting the Nicene Creed we say we believe in the “resurrection of the dead.” And when reciting the Apostles’ Creed we say the “resurrection of the body and the life everlasting.” What does this mean? It does not mean resuscitation of a corpse in the sense that one recuperates from surgery and goes back to the daily routine of life. Nor is this referring to a soulechtomy (Peters, 2015, Chapter 11), where the soul is extracted from the body to live in a bodiless realm.

Fuller philosophical theologian Nancey Murphy as well as neuroscientit Warren Brown warn us against a soulechtomy in favor of God’s promise to resurrect the body in a brief interview. Take a look at “Is Death Final” in Closer to Truth.

If resurrection is neither a resuscitation of a corpse nor a soulechtomy, could that which is resurrected look like a ka depicted on frescoes in Egyptian pyramids? Or might it resemble the occult understanding of the astral (star) body? Both the ka and the astral body, according to ancient Egyptian and contemporary occult belief, duplicate the shape of the physical body but have no material substance.

In introducing his meticulous discussion of resurrection, St. Paul speaks of heavenly bodies (σώµατα ἐπουρανία) with their glory or luster (δόξα) and identifies them with the resurrection of the dead (1 Cor. 15:40-42), which might indicate that he has an astral body in mind. But we cannot press this too far, because there is a problem here. Occult thinking presupposes a cleavage between the physical body and the supraphysical locus of selfhood in the astral body so that when one dies one does not really die. The self simply sheds its physical body and goes on, maintaining continuity between this world and the next on the basis of some built-in principle. There is no genuine death or destruction in alleged astral existence. An element of the person abides. But for Paul there is no element that perdures through death. If there is resurrection, it is new creation. Therefore, the resurrected body of the New Testament must be something different from the astral body as ordinarily understood (Peters, 2015, Chapter 11).

When St. Paul attempts to describe resurrection, he employs the image of the seed sown in the ground. That which rises above the ground looks quite different from what had been planted. But in order to guard against any possible misinterpretation in terms of soulechtomy, Paul exploits the dead-like appearance of the typical seed to say, “What you sow does not come to life unless it dies” (1 Cor. 15:36).

Notice the delicacy in the apostle’s analogy. Paul wishes to affirm continuity and discontinuity between the present and future realities. What happens is ![]() not creation out of nothing. Rather, it is a creation of something else. A dead seed is sown. But new life is harvested. Then Paul describes the eschatological harvest in terms of four complementary contrasts. “

not creation out of nothing. Rather, it is a creation of something else. A dead seed is sown. But new life is harvested. Then Paul describes the eschatological harvest in terms of four complementary contrasts. “

“So it is with the resurrection of the dead. What is sown is perishable [corrupt, φθορᾶ], what is raised is imperishable [incorrupt, ἀφθαρσία]. It is sown in dishonor [ἀτιµία], it is raised in glory [δόξῃ]. It is sown in weakness [ἀσθενία], it is raised in power [δυνάµει]. It is sown a physical body [σῶµα ψυχικόν], it is raised a spiritual body [σῶµα πνευµατικόν]” (1 Cor. 15:42-44).

To be raised “imperishable” is to be raised to everlasting life. It is not to have one’s body resuscitated so as to return to one’s daily toil. The Greek word, δόξῃ, when we use it to describe the stars, usually means luster. Here δόξῃ means honor. So, we will be raised to honor. The power into which we will be raised, δυνάµι, is the same power by which miracles of healing are wrought (1 Cor. 12:28).

Earthly Body versus Heavenly Body

Most interesting is the last of these four antitheses in Paul’s list, namely, the contrast between the earthly and the spiritual bodies. St. Paul does not describe the earthly body as one of flesh (σῶµα σαρκικόν), as one would have expected. But rather as σῶµα ψυχικόν. Literally this is the ensouled body. The ensouled body would usually be identified with the Greek philosophical tradition, as we saw in a previous post. This is what is sown but not raised. Hence, the soul dies. As if to rub it in, Paul says it is not the ψύχη (soul) that we find in the resurrection. It is the σῶµα (body).

What is raised is a “spiritual body.” We can tell from other writings of Paul that he assumes there is a war going on between the flesh (σάρξ) and the spirit (πνεύµα, Gal. 5:13-26). Flesh is the power of sin that leads to death. The spirit is its great antagonist. The spirit is the power of creation and new creation. Both powers attempt to invade and control us.

It is important to discern here that when Paul uses these terms he does not intend to make metaphysical statements regarding human nature—that is, he does not hold that flesh and spirit are distinct ontological components of each human being. This is not another version of the Greek body-soul dualism. Rather, flesh and spirit are proclivities or forces that contend for domination of the whole person, body and soul included.

One way to get at St. Paul’s underlying conceptuality here is to think of the σῶµα as the form that can exist with one or another substance, either flesh (σάρξ) or spirit (πνεύµα). German New Testament scholar Hans Conzelmann advocates this form-substance theory and contends that there is no such thing as a σῶµα all by itself. Σῶµα always exists in a specific mode of being, either as σάρξ; or as δόξα. The form is always related to its concrete mode of being. It is always either heavenly or earthly. It does not constitute the individual human being as such. Σῶµα exists on its own only as an abstract concept. This theory is of some help, but Conzelmann is not careful to show just how his idea takes account of the fact that Paul’s contrast is actually between a psychic body and a spiritual body, not between a fleshly and a glorified body. (Peters, 2015, Chapter 11).

Orthodox theologian John Behr incorporates death right into the transformation.

“Death has a positive role to play, one might even say a remedial role: having learned by their own experience the utter weakness of their life in apostasy, without God, and so turning to God ever more firmly as the only source of life, death terminates the apostasy, returning human beings to the dust from which they were taken, so that the traces of sin and apostasy can be purged from their body, and the human being can be refashioned in the resurrection” (Behr, 2006, 105).

New Testament sokdolager N.T. Wright anticipates transformation. In our resurrection, we can hope for a “trans-physical” or “transformed physical body” (Wright, 2003). To the transition and transformation we now turn.

In short, when reading the New Testament we should not rely on some inherited metaphysics holding to a body-soul or physical-spiritual dualism. To assume such a dualism may lead us astray in grasping the biblical promise of resurrection of the body. This promised resurrection is a transformation by God’s spirit.

Transformation by God’s Spirit?

Grasping the nature and scope of the transformation is a tad complicated. The spirit is not simply one substance interchangeable with others. The spirit is the power of God whereby reality itself is determined. The σῶµα πνευµάτικον is the resurrected body that is determined by the Holy Spirit. A resurrected body is the reality that we will become because God will have created us—that is, recreated us—in this form. Because it is an eschatological reality that belongs to the new creation, and because we still live amid the old creation, we cannot expect to apprehend clearly just what this means. Now we can only look through a mirror darkly. And Christ is that mirror reflecting the light of future glory amid our present darkness. What one can say with confidence is that there will be a resurrection of the human self. What one cannot say at this point is precisely what that resurrected mode of existence will look like.

It is also worth observing that St. Paul is apparently thinking this out for the first time in his dialogue with the Corinthians in Greece. The Apostle Paul is by no means simply reiterating an already existing set of ideas that previously belonged to the Jews, the Gnostics, the Corinthians, or any other group we know of. St. Paul is not offering one theory of immortality among others.

This is a case of evangelical explication at work. The apostle has already confronted the gospel and is now trying to re-present it to an audience that probably believes the material body is inimical to the spirit. The Christians in Corinth, probably heavily influenced by the Greek intellectual tradition, have misunderstood the significance of the gospel for human mortality and eternal life. We today do not know exactly how St. Paul thought of the gospel before explicating it to the Corinthians. So, for us this epistle serves as a primary symbol bearing the gospel . Hence, is subject to further explication, both critical and evangelical. (Peters, 2015, Chapter 11).

Let’s draw out an implication for our previous posts on the afterlife. The notion of the spiritual body that Saint Paul develops in 1 Corinthians 15 should be not be thought of as contrasting the physical and the spiritual. The symbol of the spiritual body should not be thought of as a way of divorcing us from the physical realm so that we no longer have to eat the fruit of the soil. Even the resurrected Jesus ate fish for breakfast (John 21:12-14). This means the spiritual body cannot be cast as anti-physical.

So, just what is Paul saying? The importance of the spiritual body is that it determines who we will be. It is our future. It marks the contrast or tension between the present and the fulfillment that is to come. It is the future spirit in metaxic relation to our present soil. We live constantly between future and present when we live proleptically.

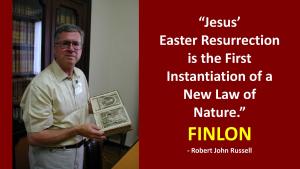

FINLON: The First Instantiation of a New Law of Nature

My Berkeley colleague, Robert John Russell (Bob), and I have been banging our heads together for decades to gain a coherent grasp of what the Bible teaches here. Bob and I along with our Heidelberg colleague, Michael Welker, brought together from around the world some of the besst minds to work on this mystery. The results of our surmising was published in a book, Resurrection: Theological and Scientific Assesments.

What Bob proposes, I think, is the best of all proposals for understanding the connection between the New Testament promise of resurrection with our physical bodies. He coined the acronym, FINLON, to describe what God did at Jesus’ Easter resurrection. God gave to the world the First Instantiation of a New Law of Nature.

Here’s how FINLON works. Bob holds on theological grounds that the processes of nature described by science are the result of God’s ongoing action as creator. The regularity of nature’s laws is the result of God’s faithfulness. But God is free to act in radically new ways, not only in human history but also in the ongoing history of the universe, God’s creation.

At the moment when God raised Jesus from the grave on the first Easter, the law that dead people stay dead was in effect. When yer dead, yer dead. It remains in effect today.

In this context, Easter leaves us with an anomaly. It could appear to be a miracle, a violaton of existing laws of nature. But Bob wants us to view that original resurrection as “more than a miracle.” It is the first instance of a general resurrection. Easter is the advent of the new creation complete with general resurrection. With the advent of God’s new creation, resurrection will become a universal law. In short, Jesus’ Easter resurrection was a prolepsis of the coming general resurrection. So, to us, Easter looks like a miracle. Yet, it’s actually mor than that. It is the First Instantiation of a New Law of Nature (FINLON) (Russell, “Bodily Resurrection, Eschatology, and Scientific Cosmology” in Peters, 2002, 3-30).

Conclusion

In this Patheos series on the afterlife, we have looked at a wide variety of options in human belief. Here in this post on “Resurrection of the Body,” we note that Christians share a vision with their siblings, the Jews. Hava Tirosch-Samuelson, whom I interviewed in an earlier Patheos post, reminds us…

“The importance of human embodiment is accentuated in the doctrine of the resurrection. The resurrection accompanies the Jewish vision of the Messianic Age (Yemot ha-Mashiah), even though there is no agreement on the what the messianic age will consist of.”

Hava sees a connection between our resurrection in the body with the eschatological messianic age. So do I. This leads to an important point: we designate God’s raising of Jesus on the first Easter a prolepsis of God’s promised resurrection of your and my body into the messianic aeon. Your and my soul–the essence of who we are as determined interactively through our lifetime–will not be lost. Rather, it will be taken up and transformed into a spiritual body [σῶµα πνευµατικόν]. Easter is the first instantiation of a new law of nature which will be unviversal in God’s promised new creation.

God’s promise to us prompts in us a zeal to live proleptically, to incarnate tomorrow’s resurrection in our lives today. According to Patheos columnist Christine Valters Painter, to practice resurrection is to love one another.

This is the Christian hope. It’s as audacious as it is awesome.

▓

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. With Robert John Russell and Michael Welker he co-edited Resurrection: Theological and Scientific Assessments.

See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Watch for his new 2023 book, The Voice of Public Theology, to be published by ATF Press.

▓

Resources

Behr, John, 2006. The Mystery of Christ. Crestwood NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Conzelman, Hans, 1978. 1 Corinthians. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Peters, Ted, 2015. God–The World’s Future. Systematic Theology for a Postmodern Era. Minneapolis MN: Fortress, 3rd ed.

Peters, Ted; Robert John Russell; and Michael Welker, eds., 2002. Resurrection: Theological and Scientific Assessments. Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans.

Wright, N.T., 2018. Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church. New York: Harper One.

Wright, N.T., 2003. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.