Short prayers! Really? Yes, prayers should be short. At least this is what Jesus says. When introducing what has become known as “The Lord’s Prayer,” Jesus remarks

Short prayers! Really? Yes, prayers should be short. At least this is what Jesus says. When introducing what has become known as “The Lord’s Prayer,” Jesus remarks

NRS Matthew 6:7 “When you are praying, do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard because of their many words. 8 Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him.”

Empty phrases packaged in many words do not impress God. God does not need to be impressed. The divine ear is attentive to our needs before we even speak of them. Hence, those long tedious strings of eloquent verbiage we have become accustomed to hearing from the lips of our priests and pastors are, according to Jesus, superfluous.

Jesus still thinks we should pray, however. God responds to prayer. “Ask, and it shall be given you,” he says in the Sermon on the Mount; “Your Father who is in heaven will give good things to those who ask him” (Matthew 7:7, 11b). Though prayers should be short, they are not without importance.

According to Patheos columnist Gene Veith, “the Bible also has many profound prayers that are extremely short, yet applicable for much of what we need to pray for. They are so short that they can constantly be in our hearts and on our lips.” Short prayers? Yep!

A person can do a lot with a few words. In particular, short prayers can have a specific focus. When highly focused, such a prayer can orient one’s life. Oh, yes, the primary purpose of a prayer is to say something to God. Nevertheless, prayers have a secondary value, namely, they guide our own way of seeing things. (Art: “Praying Jew” by Kerstin Berthold)

Prayers are lenses through which we view our life, through which we can perceive the invisible God to be present and at work in our daily affairs. Prayer is double-talk, so to speak. When we speak to God we are simultaneously speaking to ourselves. When we talk to God, we are understanding ourselves in relation to God. And this means we are understanding our true self. Even if we are searching for an invisible and illusive God, our prayers have a way of uncovering just who we truly are.

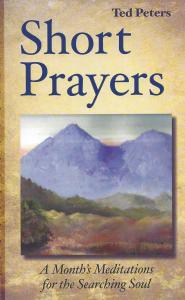

This long treatment of short prayers is the first in a series of meditative, contemplative, and petitionary prayers drawn from my widely ignored book, Short Prayers. The prayers I offer here are shorter than the Lord’s Prayer. But the accompanying meditation is longer. Try Short Prayers 1: Creation. I commend this series to you if you take quiet moments for meditation, prayer, and the closer walk with God.

The Self of the Searching Soul

Perhaps you, the reader, have a searching soul. The searching soul may from time to time ask: just who am I? Like peeling an onion, we peel and peel until nothing is left at the center. There seems to be no there there. As we look down through the layers of what makes us a self, we find we miss something. What we miss is a bottom, a center, a foundation. No matter how deep we dig into the recesses of our consciousness, only an abyss lies beneath. Introspection seems to confirm something the Buddhists say, namely, that beneath what appears to be our self is emptiness (śūnyatā). This indicates that what we thought to be our self is, in reality, a non-self (anātman).

The self cannot ground the self. If you fancy yourself to be a rugged individualist, this might come as a bad dream. Yet, it is undeniably the case that we are groundless, anchorless, adrift in an everyday world of physical interactions and mental interpretations. We can tell a story about ourselves, a life story that stretches from our birth to our death. But, what does it mean?

On our lap top we can manufacture a preferred self in the digital world of secondlife.com. We can project our avatar in a Meta Verse or Virtual World. We can project our daydreams into a virtual network that includes the self we want to be. But this second life is even more fleeting than the first one.

Like a bubble at a child’s birthday party, our entire life floats between the breath that a moment ago blew us into existence and our imminent bursting. We are ephemeral, evanescent, temporary. Before we were born, we did not exist. After we die, we will cease to exist. Perhaps someone two generations from now will remember us, maybe longer if our eulogy was particularly eloquent. But, we ourselves will not know whether anyone will ever read what is etched on our tombstone. What we know about ourselves today is temporal and temporary, here for a short span and then, and then, and then?

Fears of fleeting prompt centering. Meditation and prayer can center us. Yet, our center cannot sustain itself by itself. Only if our center is centered in God can the center hold. Prayer centers us in God.

Our prayers are shorter than even our life. Our short prayers last only a short time, but they are heard by the everlasting God. What we say defines who we are…defines who we want to be…and if our eternal God grants our prayer then we gain an eternal identity. We are what we pray, so to speak. The self we are searching for turns out to be a gift that God gives us. In prayer, we become aware of this divine gift.

In prayer we search. Then, we find that we have been found. One of Augustine’s short prayers to God gives voice to the searching soul: “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” (Augustine, 1991, p.3)

God’s Will, Not Mine

We have a paradox at work here. Only when we surrender our self do we find that we have been given our self, our true and eternal self. Perhaps, it is better to call this a miracle rather than a paradox. “True religion begins with the quest for meaning and value beyond self-centeredness,” writes the late Huston Smith. “It renounces the ego’s claims to finality.” (Smith, 1991, p.19)

This grounding of the self in our eternal God is exemplified in one of the most decisive prayers in history: Jesus’ prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane. Anticipating the likely mocking, suffering, and death that was imminent, Jesus prays:

And going a little farther, he threw himself on the ground and prayed, “My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me; yet not what I want but what you want” (Matthew 26:39).

After addressing God as Father, Jesus asks that he not have to drink the cup of death. Perhaps making an allusion to the cup of Socrates filled with poison hemlock that put an end to that Greek philosopher’s life, Jesus acknowledges his own desire to avoid Socrates’ fate. Nevertheless—and ‘nevertheless’ is a mighty big word in this short prayer—Jesus concludes by conforming his will to God’s will. Jesus is deliberately orienting his life to God’s will. He will now take courage and take whatever befalls him. By accepting his death at this time and place, Jesus defines himself as one who is at one with God’s eternal will.

Now many of us might feel a bit discouraged if we look at Jesus as our model for prayer. He probably had a strength of will that seems to surpass the rest of us mere mortals. Or we may be thinking ourselves as only beginners. But take heart. A meaningful and even powerful prayer life can begin quickly and then grow into something even more edifying.

The sixteenth century saint, Teresa of Avila, uses the metaphor of the garden to describe growth in the life of prayer. In the eleventh chapter of her The Book of Her Life, Teresa acknowledges that beginners might be shy if they think of their own hearts and minds as barren soil or full of abominable weeds. But set shyness aside. God pulls up those weeds and plants good seed right at the beginning. God then cultivates us as soil through the early stages of a developing prayer practice. Later, with the help of God, we strive like good gardeners to encourage these plants to grow, taking pains to water them frequently so they don’t wither. When they come to bud and flower, our prayers give forth a most pleasant fragrance and refreshment for life.

Writing Short Prayers

In subsequent posts I will offer a number of short prayers. Each one is intended to orient a person’s life for a given day. The hidden petition in every prayer is what follows Jesus’ “nevertheless” in Gethsemane, namely our prayer that God give us the strength and wisdom to conform our will to the divine will.

These prayers are written. They are written carefully. Not every person likes the idea of writing prayers, however. As far as we know, the Christian practice of writing prayers first appeared in the fourth century. After being transcribed they were circulated so that a more or less uniform prayer practice was developing. This upset some people. The Synod of Hippo in North Africa in 393 passed a resolution forbidding “anyone to use written-out prayers of other churches till he has shown his copy to the more learned brethren.” It appears that the nature of the objection is less against the written form than it is against the possibility that the prayer may be poorly constructed. So, if we check first with the “learned brethren” then perhaps such a written prayer may be good enough to use. Was this a form of quality control?

I believe there is an advantage to writing a prayer. During the period of writing we are concentrating. We want to use just the right words to convey just the right thoughts so that the finished product will have just the right result. Again, this is probably less for God’s benefit than our own. The thinking process that goes into the writing process is actually a discipline which gives voice to our hidden petition: we want to conform our will go God’s will.

In order to do so we need to discern God’s will. This requires reading scripture and discerning the qualities of God revealed there. It also requires examining the events of our own lives and attempting to interpret them in light of the Bible’s testimony. This juxtaposing scripture with our own lives is a thought process which we will here call “meditating”.

Meditating normally precedes prayer. It can be pursued within prayer, of course; but then it violates the short prayer principle. Such a violation is by no means injurious. There is a fine tradition of meditative prayer in the history of Christendom. Try The Upper Room. Try Daily Bible Reading. Try Daily Grace by the Women of the ELCA. Try Catholic Daily Devotions. Or try the Online Chapel.

Our pattern here—(1) a brief scripture passage; (2) a period of meditation; and (3) a short prayer—is only one way to pursue meditation and prayer. Others may be equally as good or even superior depending upon circumstances.

Collect Content as a Model for the Short Prayer

There are famous short prayers. They provide models. I believe the Collect provides a good model.

When it comes to the content of the prayer, I believe we can learn much of value from the structure of the classical Collect. The Collect is the brief prayer which follows the Gloria in excelsis and precedes the first lesson during the Western liturgy for worship. We are not sure how the idea of the Collect originated. There are at least two possibilities. In Rome on certain days masses were said at specified churches known as “station churches”. The people would gather at their own church first and then process together to the station church. The first assembling was known as the collecta, and a prayer was offered before the procession would begin. It was called the oratio ad collectam. This prayer would then be repeated after the people arrived at the station church. If this is the origin, the word ‘collect’ refers to the collecting of the people together for worship.

The other possible scenario assumes the word ‘collect’ refers to the collecting of petitions, a sort of summing up of everything we should pray for. According to this theory, the ancient church practice was for a deacon to introduce a bidding prayer. Then there followed a moment of silence in which all in the congregation would offer separate quiet prayers pertaining to the deacon’s bid. Then the presiding minister would “collect” the petitions of the people in a brief summary prayer. This summary prayer, so it is theorized, eventually became known as the Collect.

We really do not know how it began. And it does not make much difference. Of the two possibilities mentioned above, I tend to favor the first. The reason is that collect prayers are short prayers. They make only one petition. They do not seem to summarize a large amount of material. But my argument here is a deductive one and not historically conclusive.

Our concern here is the value of the Collect as a model for structuring our own prayers. There are five components.

First, it begins with an address to God, with an invocation. It calls upon God with an ascription or attribution, indicating the quality of God appropriate to the subsequent content of the prayer.

Second, it provides the basis for the petition coming up. This may not actually require extra words if the basis is implied in the name of God or the ascription used in the invocation.

Third, the petition itself is laid before the throne of grace.

Fourth, the desired result is identified.

Fifth, and finally, the prayer is terminated. The termination my identify the divine mediator in a phrase such as, “trough Jesus Christ, our Lord.”.

As an example, let us look at the most commonly used Collect for Easter Sunday. This prayer comes originally from the seventh-century Gelasian Sacramentary and has received some Gregorian as well as contemporary editing.

O God, who for our redemption didst give thine only-begotten Son to the death of the Cross, and by his glorious resurrection hast delivered us from the power of our enemy; Grant us so to die daily from our sin, that we may evermore live with him in the joy of his resurrection; through the same thy Son our Lord. Amen. (Anglican, 1929, p.165)

Or,

O God, you gave your only Son to suffer death on the cross for our redemption, and by his glorious resurrection you delivered us from the power of death. Make us die every day to sin, so that we may live with him forever in the joy of the resurrection, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen. (Anglican, 1929, p.165)

Here we see God is invoked and described as the one who sent the Son to suffer the cross .

God is also the one who raised the Son gloriously on the first Easter. This is the basis of the petition which will follow. Our petition is that we die daily as Jesus died, that is, that we die to sin. We are asking that our lives be conformed to Jesus’ life. Why? For a specific result. The result is an extension of the petition: that we may share in the Easter resurrection and live with Jesus forever in God’s kingdom. The prayer is then terminated in the name of Jesus Christ, as nearly all Collects are. Actually it goes one better by concluding with reference to the Trinity: each of the three plus the unity.

“The genius of the collect,” writes John D. Witvliet, “lies in the apt pairing of attribute and petition, with the acknowledgment of a past action of God grounding the petition for similar future action.” (Wityliet, 2008)

Some Collects are fancier than others. Especially in Collects written more recently we find “many words” and the “heaping” of phrases. The older the Collect, the shorter it is likely to be, expressing only one clearly-defined petition. What we can benefit from most is emulating the idea that a short prayer focuses on one single thought.

In fact, I am pressing this concern even further than the Collect itself has gone. Instead of five essential components, I will be working with just two: the invocation with an implied ascription plus the petition. This, I think, will increase the focus and, thereby, increase the ability of the prayer to orient our life for the day in which it is offered.

A similar prayer structure is embodied in the acronym ACTS. According to ACTS, each prayer should have four components: Adoration, Confession, Thanksgiving, and Supplication. Recommended by Keith Miller and Bruce Larson in the The Edge of Adventure and more recently by Bill Hybels in Too Busy Not to Pray, the ACTS formula presents a rounded or balanced prayer aimed at forming the whole of one’s disposition. Certainly this applies appropriately to the larger picture, to what we might call the “woods” of our spirituality. In this book, I wish rather to focus on just one of the trees which belong to this larger forest, namely, the short prayer with a single thought.

I obviously believe short prayers well integrated with life are helpful. Yet, other forms of meditation and prayer should not be forgotten. Please let me be clear: what we find here in the short prayer represents one dimension of the larger discipline of Christian spirituality. There is much more to prayer than what is offered here. Nevertheless, what I am laying before the reader is an attempt to take seriously Jesus’ emphasis on short prayers and combine it with the interpretation of our daily life in light of what scripture says.

Pray in the Morning…and All Day

When should we pray? In 1 Thessaolonians 5:17 St. Paul says, “pray constantly.” If by this St. Paul means a general disposition of receptivity to God’s leading, then in principle we could be prayerfully disposed at all times. We can maintain a prayerful mood even while going about the day’s business. But, if we want to focus our thoughts sharply through a short prayer, then we need to pause and concentrate. We need to push all other items out of our mind for at least the five minutes it takes to meditate and formulate.

So I suggest the early morning before the day’s activities get under way. Greet each new day with a prayer along with a vitamin pill or cup of coffee or whatever the normal routine. A short prayer at this time will have the advantage of orienting the course of the day’s events. It will provide a set of lenses, so to speak, through which one can perceive and interpret and re-orient one’s activities. If the opportunity arises, then the same prayer could be repeated at noon and in the evening for reinforcement.

For some people, of course, the early morning does not work. The still sleepy eyes are bleary, and sipping coffee is the most nourishment one can handle while racing to the day’s responsibilities. So, if the morning is out, then, try the evening. A short prayer preceded by a moment of meditation just before drifting off to sleep in the evening may work better. Still better might be during recess at school or coffee break at the office. The key, I think, is the regular habit. Fit it in where it fits. As prayer power begins to have an impact, then it will grow in importance and other things will move aside to give it more room. When this happens, then we know growth is taking place.

Perhaps, instead of fitting prayer into your fixed schedule, you might wish to reorganize your day’s schedule around prayer. If you would like to feel the rhythm of the day, set your mental alarm clock to specific times when you say to yourself, “now, it’s time to pray.” Our Muslim friends do this five times per day. This evokes a God-consciousness that pervades the mind even when not actually formulating prayer petitions.

Why not seven times per day? Phyllis Tickle calls this practice “fixed-hour prayer.” The tradition of seven per day comes from “the hours or keeping the offices [which] is one of the seven spiritual disciplines that came directly into Christianity from Judaism.” (Tickle, 2007, p.xvii) Whether prayer complements your fixed schedule, or whether you reorient your schedule to fit your prayer routine, it is the mixture of prayer and life that elicits God consciousness and the willing of what God wills. Prayer constructs the self, your eternal identity.

Have you thought about praying while walking? Jack Wellman has. Try it. To your FitBit add perambulation meditation.

Prayer & Love

One more thing. Perhaps the most important thing. We’ve been assuming that prayer has power only when it is sown into the fabric of our total life, when it is part of the seamless whole. In addition, I believe there is an inextricable tie between prayer and love. Prayer is authentic only when it is an expression of love; yet, paradoxically, growth in love is a product of prayer. Love and prayer constitute a mutually reinforcing circle, or spiral. If we are feeling loveless, prayer can draw the power of God’s love in. When our whole being is saturated with love, then prayer becomes a channel for the activity of God in our world. Love and prayer belong together. Poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge says it in Part VII of the “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓

Works Cited

Anglican. (1929). The Book of Common Prayer. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Augustine. (1991). Confessions, tr. Henry Chadwick. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, H. (1991). The World’s Religion. New York: Harper.

Tickle, P. (2007). The Divine Hours. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wityliet, J. (2008). Collective Wisdom. Christian Century 125:15, 25.