This post is part of a ten-part series drawing from the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films. You can read the introduction the series here, along with the schedule of films to be featured.

This post is part of a ten-part series drawing from the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films. You can read the introduction the series here, along with the schedule of films to be featured.

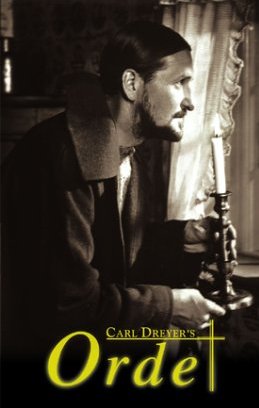

Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1955 film, Ordet, is based on a play by Danish pastor and playwright Kaj Munk. During the Nazi German occupation of Denmark, Munk refused to bow the knee to the Third Reich. In 1944, he was killed by the Gestapo and dumped in a ditch as a result. (You can read more about his theology–especially about the Good Samaritan and responsibility to neighbor–here.) Munk’s play, written in 1925 and first performed in 1932, was called In the Beginning Was the Word.

This is a strange film–cerebral, talky, theatrical, and slow. It centers around an elderly Danish farmer named Morten Borgen and his three sons. One son, Mikkel, is an agnostic or atheist but happily married to the heart and center of the film, Inger. Inger is a woman of simple, embodied, yearning, joyous faith. She brings warmth and love to everything and everyone within her milieu.

Another son, Johannes, is mentally ill and believes himself to be Jesus Christ. He spends most of the film chastising the rest of the characters for their lack of faith in him in a strange, mournful voice. He stares straight ahead, distanced from the other people around him, cut off, alienated. It is said that he went mad through too many studies and particularly through studying Kierkegaard.

The third son, Anders, finds himself in love with a girl from a “born again” Christian sect in the village, the daughter of the tailor, Peter. A longstanding religious feud between the Christian sects of Morten and Peter stands in the way of the romance, and both men spend a great deal of time explaining how their sect is right and the other is wrong. Instead of warmth, love, and unity among those who obviously do believe in Christ as Savior of the world, there is enmity and one-upmanship, a sorry state of affairs that sounds all too familiar today.

There are many key conflicts in this film. Morten is struggling with a conflict of faith in relation to Johannes’s mental illness. He has spent many hours praying for Johannes to be delivered, but his petitions have only been met with silence. As a result, his faith has become jaded, cynical, and tired. “Miracles don’t happen anymore,” he tells his daughter-in-law, Inger. She responds with a confidence in God in the midst of His silence, a steady trust in His goodness despite all the bad that has happened. I found myself believing Inger and gravitating toward her, as the film obviously intends the viewer to do. The film seems to be saying that trust in God is still possible in exactly this broken, enlightened world in which we live. But it will require a simple heart of love to appropriate, not sophistication and self-effort.