This post is part of a ten-part series drawing from the Arts and Faith Top 100 Films. You can read the introduction the series here.

Please note that this article contains spoilers.

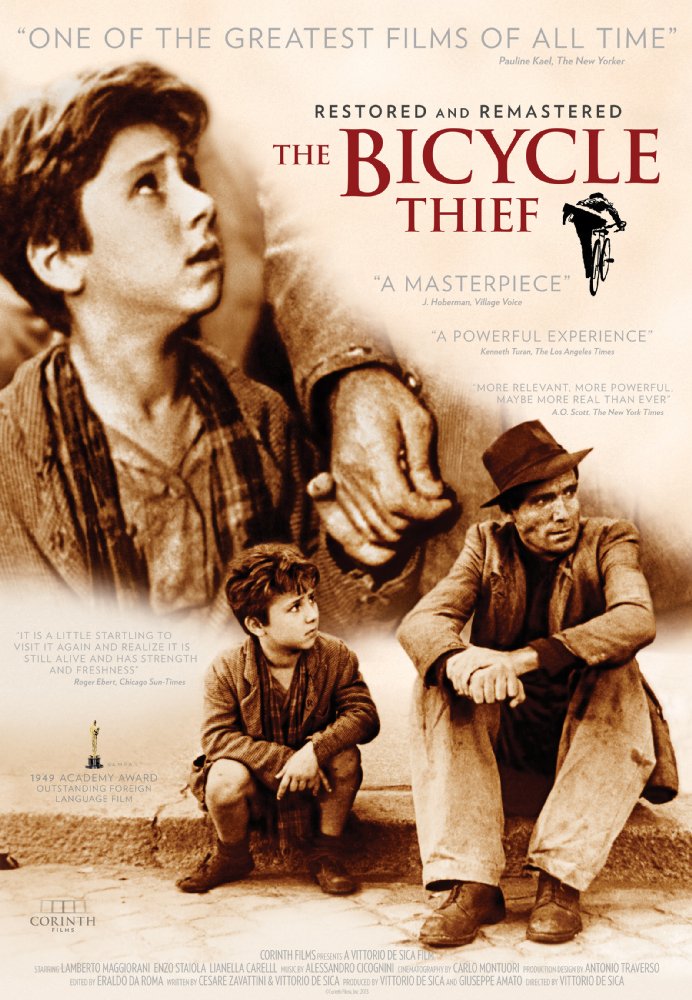

I first heard about The Bicycle Thief, the 1948 film by Vittorio de Sica, at a writers conference, where it was held up as an admirable example of spare plotting and basic story structure, and described as one of the greatest films of all time.

In this film, a poor man named Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani) is trying to support his two children and wife in the midst of the terrible post-war depression in Italy. Ricci catches an unlikely break; he is given a job hanging posters around Rome. It’s a good job that will provide a future for his family, but there’s a catch: in order to keep the job and work fast enough for his employers’ requirements, he is required to have a bike. Ricci, having previously hocked his bike to provide for his family’s basic needs, has no choice but to now pawn the sheets off his very his bed in order to get his bike back. But he does it, at the suggestion of his wife, Maria (Lianella Carell).

Things are looking up! The future is bright! But on the very first day of his new job, Ricci’s bike is stolen. For the rest of the film, a desperate Ricci will search the city of Rome for his stolen bike, desperately hoping against hope that he can find it and keep his job so his family will not starve.

By the end of the film, a desperate Ricci has not yet recovered his bike, though he has unsuccessfully attempted to confront the thief who took it, only to be unable to press charges for want of evidence. Throughout the entire film, we as viewers have been encouraged to identify with Ricci and to look at his dilemma in clearly black-and-white terms. Ricci is the good guy: the poor man who wants to provide for his family, against whom a thief has done evil. Throughout most of the film, we look at the story through the lens of good guys and bad guys, without much nuance in the middle.

And yet, when he is backed into a corner, we see Ricci desperate and tempted to steal an abandoned bike. By now we are deeply sympathetic to his plight and the filmmaker takes this opportunity to move us as the audience to a new place. Rather than despising criminals, we have changed our perspective to better understand what might push a person to crime. Perhaps, at least sometimes, criminals are desperate people. Perhaps criminals are sometimes people who society has failed.

The young son of Ricci, Bruno (Enzo Staiola), functions as the conscience of the film. In his plaintive eyes we see rejection of the act of stealing. The film ends with Ricci, having stolen the bike, gotten caught, and gotten miraculously released without charges, walking with anguish and shame down the road, his son by his side. In that final scene, we see in young Bruno’s eyes and in the little hand taking hold of his father’s the forgiveness of a child who understands the desperation of his father, however much he hates the fact that his idealistic idolization of a beloved parent has been forever undone.

This film reminds me of a recent documentary series that has been released on Viceland, Black Market. In this series, Michael K. Williams (best known as “Omar” from The Wire) gets to know people around the world who engage in crime, with an eye to better understanding what leads them into their lawless behavior. What makes people step over the line? Williams’ goal seems to be to humanize people that society often conveniently dehumanizes: criminals. We like to think of these people’s behavior in isolation from their life histories, because that’s neat and tidy and convenient for us. But when we learn their histories, we come to understand how society has often failed these people, how shameful they often feel about their own crimes, their desperation, their lack of vision, their humanity. (Click here to listen to Terry Gross’s terrific interview with Williams.)

Some believe that if we humanize or empathize with criminals, it will make us “soft” and unable to set boundaries against evil behavior. But I think we can both empathize and set boundaries in society. We can start by working toward a society where people don’t have to make desperate decisions, or at least not so often. We can work toward a society where our neighbors get a fair shake and where people who want to work have the opportunity to do so. We can work toward being more of a society of mercy.

But we can simultaneously work toward setting boundaries for destructive behavior and choosing also to empathize with the victim of crime, honoring their common humanity. With The Bicycle Thief, we spend the entire film empathizing with Ricci’s plight, one which he has not at all brought on himself. We see the impact crime has on him and his family and the desperate straits in which they find themselves. But in that identification with Ricci the crime victim, we of course come to identify with the owner of the bike Ricci ends up stealing too. That man has a family too. The loss of his bike might also have a terrible impact on his life. The film manages to humanize both crime victim and crime perpetrator in the one Ricci. This strikes me as exactly the right balance. People of faith are called to recognize our common humanity, our common Imago Dei-ness, in every person that we encounter.

When it comes to current events, I wonder what The Bicycle Thief might have to say to a society that spends a great deal of time demonizing certain groups such as terrorists, mass shooters, and drug addicts. Within the lives of perpetrators of these crimes, we often find the presence of some form of alienation. We might find poverty, depression, despair, or that they are in some way being shut out from society. We might see in young immigrants a sense that they fit in nowhere in society. Or the alienation might be expressed emotionally in young people (or old) who have never learned how to process disappointment and anger. Certainly none of this forces anyone commit crime. And sometimes these factors are not in play. But I wonder if coming to better understand how society fails at least some of these people might help us to better empathize with how they end up doing terribly destructive things. How can Christians, in particular, be instruments of reconciliation in an alienated and fragmented society?

All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation: that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting people’s sins against them. And he has committed to us the message of reconciliation.–2 Corinthians 5:18-19 NIV

Christians are to be people of reconciliation, first between God and humans, and then between human and human. We are called to help create family, home, and care for those in society who are alienated. We may not be able to fix a broken world, but we can help to bring little pinpricks of light in the dark. Just because we cannot solve every problem of society doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try our best to serve our neighbor and help alleviate his alienation.

Likewise, Christians are to be people of reconciliation in the seeking of justice for victims. If we identify with the criminal, we ought also to identify with the victim who has been violated and alienated. We ought to do all we can to restore the victim to life and wholeness and safety. If we don’t hold those who commit terrible acts responsible for their crimes, we fail to humanize the victims. The Bible repeatedly speaks of the cry for justice in the midst of evil. We should consider the pain of those who have been wronged and seek to bring them healing and restoration. But we should do this by means of redemptive, not retributive, justice–a justice that does not discard but works to heal and restore.

Question for readers: Which do you have the hardest time humanizing? Victims or criminals? How might you change that?

——————-

Community discussion guidelines:

Because this is a Christian blog, the things I’m talking about will obviously be topics that people feel strongly about in one direction or another. Please keep in mind that this is a place for substantive, respectful, constructive conversation. All perspectives are welcome to discuss here as long as all can treat each other with kindness and respect. Please ignore trolls, refuse to engage in personal attacks, try not to derail the conversation into divisive rabbit trails, and observe the comment policy listed on the right side of the page. Comments that violate these guidelines may be deleted. Vulgar remarks may result in immediate blacklisting. For those who clearly violate these policies repeatedly, my policy is to issue a warning which, if not regarded, may lead to blacklisting. This is not about censorship, but about creating a healthy, respectful environment for discussion.

P.S. Please also note that I am not a scientist, but a person with expertise in theology and the arts. While I am very interested in the relationship between science and faith, I do not believe I personally will be able to adequately address the many questions that inevitably come up related to science and religion. I encourage you to seek out the writings of theistic or Christian scientists to help with those discussions.

———————-

Image source: IMDB.com