Meredith Warren is the perfect person to spearhead an academic project about Good Omens and the Bible. I spoke with Meredith recently about her latest book, Food and Transformation in Ancient Mediterranean Literature, which is about hierophagy or “sacred eating” as depicted in literature from ancient Greece, ancient Judaism, and early Christianity. I’m looking forward to releasing that podcast at some point in the second season of the ReligionProf podcast, probably closer to AAR/SBL in November at which the book will be available.

If you’re not sure what the connection is between Good Omens and eating, take a look at this article exploring the significance of food and angelic eating in the show:

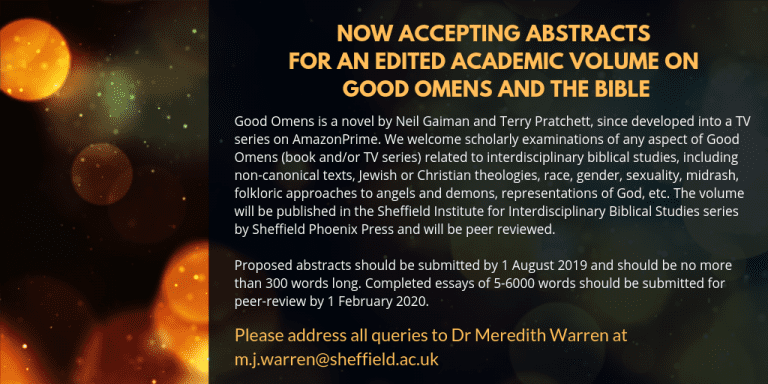

And now, here’s the call for papers for the volume:

Good Omens is a novel by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett, since developed into a TV series on AmazonPrime. We welcome scholarly examinations of any aspect of Good Omens (book and/or TV series) related to interdisciplinary biblical studies, including non-canonical texts, Jewish or Christian theologies, race, gender, sexuality, midrash, folkloric approaches to angels and demons, representations of God, etc.

The volume will be published in the Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies series by Sheffield Phoenix Press and will be peer reviewed. Proposed abstracts should be submitted by 1 August and should be no more than 300 words long. Completed essays of 5-6000 words should be submitted for peer-review by 1 February 2020.

Please address all queries to Dr Meredith Warren at [email protected]

Also related to this topic:

The Omen, Good Omens, and Why Neil Gaiman is Not the Antichrist

Good Omens: Fast Friends at the End Times

https://brucegerencser.net/2019/06/good-omens-dear-fundamentalist-christians-dont-like-a-tv-program-dont-watch-it/

And in case you missed it, there was hilariously a petition to Netflix to cancel the show – which was never on Netflix, and was already over by that point!

I haven’t read the novel, but the TV show Good Omens begins with narration by God, who explains how Archbishop Usher was almost exactly right about the date of creation. Hopefully that is enough to clue most viewers in to the fact that the story is satire. But I think it nonetheless has some profound theological insights to offer.

From the very first episode there is mention of a “Great Plan” which is said to be ineffable. That proves to be a central point later on. We also have discussion between an angel and demon who become best friends over the course of the story. The angel gave away his flaming sword to Adam and Eve. The demon, who was the tempting snake in the garden (played hilariously by David Tennant with reptilian eyes), says that it would be funny if the angel did wrong thing and the demon the right thing. “A demon can get into a lot of trouble for doing the right thing,” he remarks.

Another major feature in the story is the book The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch. Hers is the only completely accurate collection of prophecies ever to be written, but they are often vague and only intelligible with hindsight. But she foresaw that the time in which the main story is set would be the time in which the Antichrist would appear. The Antichrist turns out in many ways to be as crucial a character as Aziraphale and Crowwley, the angel and demon, and the story explores the interesting perennial question of nature vs. nurture. The arrival of the Antichrist requires that he be substituted for a baby that has just been born, without the parents’ knowledge. The aim is that he grow up as the son of an American diplomat. But in the hospital run by satanic nuns where all this is organized to take place, a mix-up occurs.

In connection with the theme of Meredith Warren’s book and the podcast we recorded, Aziraphale eats sushi, while Gabriel says he wouldn’t sully his temple with that base matter. This accurately reflects the perspective of many ancient authors about what angels should and shouldn’t do, although I’m not sure whether Neil Gaiman knew this.

For those interested in music, there is also a moment in the first episode when Crowwley asks how many first-class composers they have in heaven. He mentions that Mozart, Beethoven, and all the Bachs are in hell. Once again one wonders whether this reflects a lack of knowledge of Johann Sebastian Bach’s faith, or is pronouncing it inadequate based on an awareness of his life.

In episode 2, Crowley mentions (not for the last time) that he didn’t mean to fall, he just hung out with the wrong crowd. More satire is offered, as War (one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse) arrives and oversees an incident in which human political leaders kill one another over the question of which of them gets to sign a peace agreement first. There are potentially profound remarks, such as “Evil always contains the seeds of its own destruction,” and thought-provoking ones such as “Angels aren’t occult. We’re ethereal.” Aziraphale owns a used bookshop, and in it he has copy of John of Patmos’ scroll. Looking at it again, he discovers that 666 is a phone number, leading him to the misplaced Antichrist.

Episode 3 focuses much of its attention on flashbacks to earlier moments in history. Noah’s flood is just aimed at locals, we are told, as the Almighty is not upset with the Chinese, native Americans, or Australians. When Crowley observes that killing kids seems more like the sort of thing that his lot should do, Aziraphale insists that “You can’t judge the Almighty.” With a wink and a nod to a young-earth creationist conundrum, one of the unicorns runs away before the rain begins. If there is a scene that seems anticlimactic, it is the crucifixion scene. It is not long before eating features prominently again: oysters, crepes, brioche, and pears. There is also reference to a picnic and then dining at the Ritz. We also learn that holy water destroys demons completely, which will be significant later on.

In episode 4 Aziraphale is told to “lose the gut” (he has gone soft eating human food). There is also an appearance of the Megiddo archaeological site (Armageddon) and reference to the Metatron. In episode 5 the flaming sword returns, suggesting that Aziraphale’s kindness and generosity was a good thing in the long term.

Episode 6 brings the story to its climax, and returns to the idea that the Great Plan is ineffable. The problem is that both angels and demons are sure they know what that plan is nonetheless, and are working towards the final battle based on that assumption. Adam, the young Antichrist, had been getting carried away with his power and a desire to reboot the Earth, but has a change of heart. He is told that he is better than heaven or hell incarnate: he is “human incarnate.” Ultimately Satan shows up, and rather strikingly refers to Adam as his rebellious son. This is perhaps one of the most profound moments in the show, since rebelliousness on the part of the “angelically inclined” features regularly in Christian literature, whereas the possibility of demons or the Antichrist rebelling against their tendency and preferring to do something good is rarely considered in a similar way. Adam tells Satan, “You’re not my dad, you never were.” The angelic and demonic best friends muse, “What if the Almighty planned it all along? Wouldn’t put it past her.” One of them also tells the other, “You don’t have a side anymore. Neither of us do.” That is perhaps the most crucial theme of the show, the idea that an angel and a demon forging a friendship can save the world when polarized opposition leads to conflict, war, and destruction.

The final scene with Adam the Antichrist sees him disobeying his (human) mother and leaving the garden where he has been grounded, eating an apple after he does so. There is a nice fake-out that Aziraphel and Crowley engage in. And there is the suggestion that the big conflict will not be heaven vs. hell, but heaven and hell against humanity will be the big one.

At the end, it is time to leave the garden. A perfectly apt question closes the exploration of the theme: “Tempt you to a bit of lunch?” But the show leaves us with an overall question to ponder: isn’t hope and ultimately salvation dependent on those of us who might be inclined to be enemies instead forging friendships that cross whatever category boundaries might otherwise separate us? Angel and demon, antichrist and kid, witchhunter and witch, etc.

Being willing to eat together is often crucial to that process.

Have you read or watched Good Omens? What are your thoughts on its theological vision?