This continues my recap of the “Future of Gen Ed” event that Inside Higher Ed hosted. Sorry that I have allowed such a long time to pass since part 1!

Since I last wrote, Inside Higher Ed has had countless pieces related to the themes of this day workshop on general education and core curriculum requirements. These include:

Articles Overstate Millennials’ Loss of Interest in Higher Ed

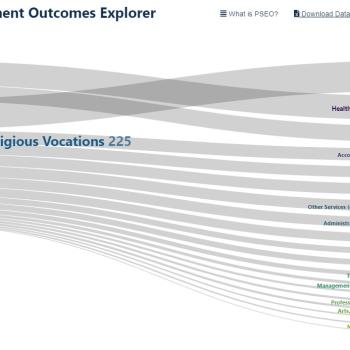

Study Student Learning Outcomes

Beyond Distribution Requirements

Finding the right models for higher education

Illustrating Applied and Practical Arts

Inside Higher Ed also held a multi-day workshop on the Future of Higher Ed. Here are recaps from someone who participated in Day One, Day Two, and Day Three of that workshop with a slightly different but related focus to the one I am blogging about here.

Colleen Flaherty, Faculty Affairs Reporter for Inside Higher Ed (who wrote the recap I linked to in part 1 of my own recap of this event) led one session featuring panelists from institutions that have recently gone or are currently going through revisions to their gen ed program. One of them sought to move from “9 ways of knowing” to focusing on knowing how to think. “Thinking Digitally” was part of that.

Linda Bell from Barnard College said that a gen ed or core that is “fundamentally working” is not good enough. There have been lots of changes in the 16 years since their gen ed requirements were implemented. Students tell us changes are needed, faculty express dissatisfaction, and there was support from the board and faculty for change. “Faculty own the curriculum and have to be involved from the ground up.” They were told they can “wipe the slate clean” if they want to. The administration had no stake in the game other than to “get it right” by listening to faculty and students. A lot of community-building took place. Some cynically remarked that they had simply replaced “9 ways of knowing” with “6 ways of thinking.” But their old core had been shown to be outdated, inflexible, inequitable, and also to lack the rigor the institution demanded. They eliminated all exemptions based on the argument that no high school class is the same as a Barnard experience. That’s one thing that attending this workshop really drove home. There is no one approach when it comes to things like students bringing in transfer credit, dual credit, dual enrollment, AP, and IB. Some accept nothing, some accept everything, and there is a whole spectrum in between. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

They have maintained a 2,2,2,2 (humanities, social science, natural science, electives) distribution requirement. It is old fashioned, but flexible. They added digital courses including ones in music, dance, arts. Students love them. They have moved resources in direction of student demand, and feel that the impact has been positive.

Mary Hinton from the College of St. Benedict talked about their new “integrations curriculum” which comes online in fall 2020. It aims to give a more cohesive experience to students. The change was not mandated by the administration: the core was expanded, and this was driven by faculty. It is important to ask explicitly why core matters to liberal arts students (who may naturally incline to the broad and intellectually curious approach that core requirements seek to foster/impose in other sorts of institutions), and how we meet our goals. They engaged students in conversation from the outset. Asked which courses they thought would have the most impact on them outside of college. The core reform was not driven by students, but the faculty still wanted to hear their perspective and valued their input. A key point that was made is that the liberal arts are not encapsulated by a collection of courses, but rather intentional integrated learning.

They privileged several things in the design and implementation of their new core:

- Move from a teaching to a learning mindset. We now have great information about how people learn. Putting the focus here does not represent a diminution of content.

- Integrate learning across 4 years so that the result is a developmental and scaffolded model, with themes introduced early that students come back to throughout their experience.

- Openness to interdisciplinarity, faculty working together. Perhaps most importantly, the courses and skills are emphatically presented as foundational to their major, not an add-on or check boxes.

- Faculty were open to how community engaged holistically. The First Year Experience is co-led by student affairs.

When it comes to assignments in a core like this, an integrations portfolio can be very meaningful, placing the focus not on individual isolated courses but connections between them. Key 21st century skills are learned: construct, deconstruct, reconstruct, work with information.

Melody Bowdon of University of Central Florida is at an R1 institution with 59,000 undergraduates. They are in year 3 of a reboot of their gen ed requirements after it being the same for 17 years. Their focuses include “Direct Connect” and integrated learning, connecting STEM and humanities. Faculty development is a centerpiece of their current effort. She tweeted info about this, and there is also a website: https://curriculumalignment.ucf.edu/

Launching a downtown Orlando campus, they co-built it with a state college institution, rather than the usual model where one just has a building on the other’s campus. They aimed for an integration of student affairs and academic affairs efforts. Improving advising is crucial and yet never easy or simple, and thus often never gets tackled, much less tackled effectively. This needs to be a priority.

They provide students with a curriculum map, and offer a Bachelors in Integrative General Studies. Physics and all other disciplines have to explain how they are integrating goals such as cultural awareness into their curriculum.

The timeline for changes to general education/core is important. It causes problems if an institution moves too quickly or allows the process to drag on too long. Design and implementation need to be separate processes.

They developed rubrics for learning, and coded classes to indicate how they relate to the modes of learning around which Barnard’s core is focused. They speak of them as “foundations.” The institution made a promise to reevaluate its “modes of thinking” every 5 years, since this component of student education always needs to be modern and rigorous.

A key question that always comes up: Do we remove something when we add something? Some have called for a requirement related to sustainability. Around 25% of a typical undergrad’s courses at Barnard are gen ed. But where that general education focuses can and should change over the years. Barnard had a strategic plan that addressed distribution of resources, a plan as well as a process. Other things that were mentioned were “Liberal Arts for Life” and the development of an “inclusion ecosystem.” Assessment was built in from outset: How will we measure success and from what vantage points? It is easy to sum up a core in terms of “5 ways of thinking, 4 modes of engagement.” But there has to be clarity on what that means and how we tell whether it is being accomplished. A core has to be dynamic. One way of accomplishing that is for there to be themes that are intentionally dynamic, and for the interpretation and focus of those themes during a particular period to be faculty driven, so that the core does not remain static even in between more structural and systemic curricular reevaluations and revisions.

Provosts found it refreshing and encouraging to discover how much students shared the institution’s valuation of gen ed. For state institutions, the state constrains what an institution can do. At any institution, advisors need to explain the reason for taking courses and connections between them.

In one process they drew on 200 “power professors” who had taught gen ed courses 5 times in the past 3 years. There were grants, meetings, workshops, and cross-disciplinary small groups, all for faculty development. In one case a physicist ended up working with an instructor in speech, making connections between their courses. They called it a “Reboot Camp.” You can see more about this on the UCF “Gen Ed Refresh” page. Different institutions are bound to be different when it comes to gen ed: some classes at UCF have 500 students in them!

Creating a community of gen ed/core faculty, with meetings, awards, appreciation, compensation, and recognition. All fields and ranks should be represented.

Matt Sanders spoke about “Becoming a Learner.” I love the image of gen ed as like “cross training,” less about moving muscles in the precise activities that you may confront in everyday life, and more about building muscles in ways that make them ready to tackle foreseen and unforeseen needs for physical strength. The same applies to mental strength.

Students select where they go based on their understanding of our mission and values. If we are clear about how our values are expressed in and through our curriculum, we get buy in from students. This in itself moves gen ed out of its silo, so that it becomes how we define ourselves, who we are and want to be in the world.

“Your curriculum should be your main attraction for your institution” (Mary Hinton).

Benedictine values are reflected at one institution through a theology requirement that students take two courses, one in Catholicism, while the other can be something else. They seek to be inclusive and welcoming as they represent that identity. “Charism that enlivens our campus.” Some institutions offer courses about their local context, e.g. Barnard courses about Harlem.

Gen Ed reexamination sometimes leads to discovering how much is already there and making it explicit, e.g. physics faculty talking about philosophy and history. They had already been doing it. UCF shifted its focus onto SLOs instead of disciplines – something Butler University did the last time we revised our core!

There was a question during the Q&A session from a representative of the University of Puerto Rico, about community service. At St. Benedict it is embedded in the major. One of their “ways of thinking” is thinking about society in scientific terms. There is not much double counting at St. Benedict. Barnard, by way of contrast, doesn’t have a community service requirement. They do double count, and are more flexible, but with no double counting within the same category. The flexibility of their approach resides in the fact that one course may fit more than one category. I imagine that my course on the Bible and Music might be the sort that could be taken to meet different possible core requirements at that institution.

David Alvarez from De Pauw asked about the role of the board of trustees in gen ed/core revision. They are stewards of an instiution’s mission, while faculty put meat on bones. The board are not the ones to say what the curriculum should look like. But they should look to see whether curriculum is meeting stated goals, interrogating and assessing processes and outcomes.

I will try to post the third part much sooner than I did the second. In the meantime here are a few links of related interest:

Inside Higher Ed on communicating the value of higher education, and attacks on disciplines in Brazil.

Liberally-educated business leaders

Reports from a national survey on first year and capstone experiences

And something on senior experiences

Harvard magazine on reforming high school

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-market-correction-in-the-humanities-what-are-you-going-to-do-with-that/

Conservative views of higher ed

The critical skill the liberal arts provide to the STEM industry

https://futures.georgetown.edu/bridge/?cid=nwsltrtn

On privilege and professors:

And finally, a call for papers:

https://relcfp.tumblr.com/post/187328818507/cfp-undergraduate-research-as-a-high-impact