How do we articulate the purpose and value of the liberal arts? In a time when rising debt and mounting anxiety about employment push college students into professional pathways, it is no doubt important that people like me explain the economic benefits of studying the arts, sciences, and my beloved humanities. But the liberal arts aim at much more than employment, all the more so when pursued within the context of Christian higher education.

So I’ve occasionally played around with metaphors that might help us understand the harder-to-quantify value of the Christian liberal arts. Earlier this month, I tried a variation on this theme when I was asked to give the keynote address at the 2019 Twin Cities Undergraduate Theology Conference, a joint effort of four evangelical colleges: Bethel University, Crown College, North Central University, and the University of Northwestern St. Paul. I suggested we consider how theology, biblical studies, history, and other liberal arts disciplines are, in some ways, similar to Christian sacraments.

You can read the full text of my remarks at my own blog. What follows below are excerpts.

Whether theology or history, humanities or sciences, the liberal arts are liberating arts, freeing us from personal prejudice and cultural captivity. In particular, the humanities are about our shared humanity, in all its beauty and ugliness; our fields ask of God the psalmist’s question, “what are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?” (Ps 8:4)

If that’s true, then pointing primarily to earnings potential will just impoverish the meaning of our model of education. We need to use language that’s richer than dollar figures. Whether we’re theologians or biblical scholars, historians or lit scholars, we ought not neglect the discourse we know: narrative, allusion, reflection, poetry, metaphor…

So let this non-theologian tentatively suggest a theological simile for what our disciplines accomplish within the larger context of the Christian liberal arts.

Our disciplines are like the sacraments

I’m thinking of analogy more than allegory. I’m not saying that history and theology are symbols of certain rituals. By using simile here, I want to do what all of our disciplines do: stretch our imaginations.

In the same way that I ask my history students to imagine what it was like to be a French peasant on the eve of revolution or a Jewish victim of the Shoah, in the same way that theologians young and old reach out with their minds to imagine a God who surpasses understanding… tonight I want to push you to think afresh about intellectual work that is more than professional, even more than academic.

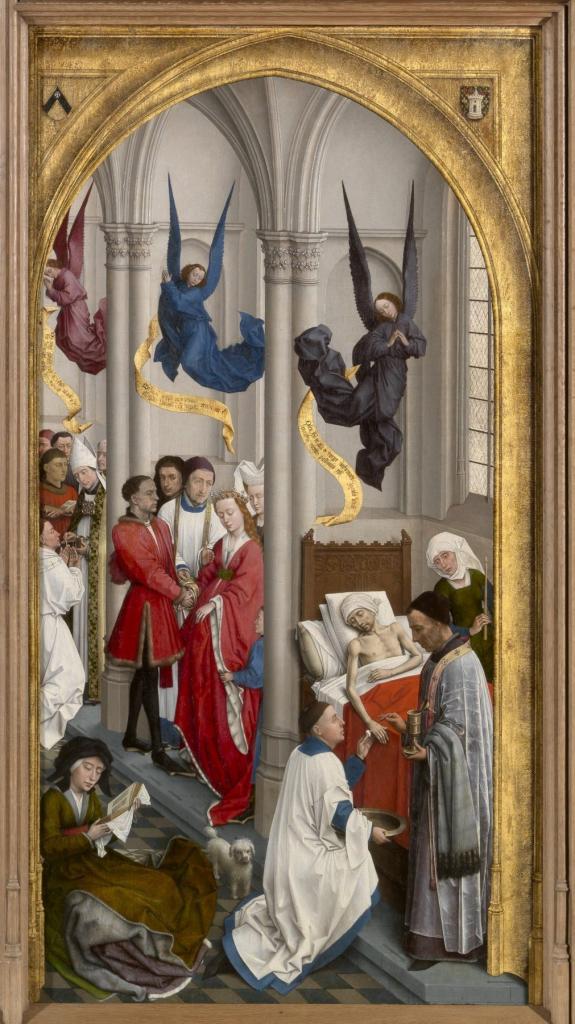

And what better way to do such imaginative stretching than to consider our disciplines by comparison to the sacraments, what Irenaeus called “the mysterious operations of God.” Specifically, I want to think out loud about the seven late medieval sacraments depicted in this famous 15th century altarpiece by the great Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden.

Now, I’m a Protestant: I don’t think that all of these rites are actually sacraments ordained by Jesus in Scripture. Some of you don’t even believe in the sacraments. Some of you might add other ordinances, like footwashing. But however we define them, I think these seven practices can help us to think more imaginatively, as Christians, about what our academic disciplines do to and through us.

Baptism

…We might ask, In what ways does a liberal arts education help us to die to our sins and rise to new life? At the very least, here we should consider that the baptismal font or pool is not a finish line, but a starting block: the anticipatory beginning of a Christian journey, not the proclamation of its completion.

…A Christian college is not the church, but as a professor at a Christian college, I am fulfilling a baptismal vow that I’ve made again and again to sisters and brothers in Christ. To teach any discipline in this setting is to share in the nurturing of fellow Christians who are still young in their faith; whether we teach history or theology, we are encouraging people like you to know and follow Christ; we are caring for you as Christ’s own.

Confirmation

…there is something confirming in the Christian liberal arts: as you learn to think about God both devotionally and rigorously, as you read the Bible as both true and complicated, as you find in history not just inspiration but tragedy, you start to “put an end to childish ways” and see God, the Church, yourself, and others “more fully” — if never quite perfectly (1 Cor 13: 11-12).

This is the great adventure and risk of our education: we cannot assume that you will reach its completion still desiring to follow Jesus. But if you do still say Yes to his invitation, it will be a more authentic, more assured, more committed Yes.

Penance

But also a more sober Yes. Because saying Yes to following Jesus means saying Yes to taking up his cross (Matt 16:24).

…As a history professor, even at a Christian college, I’m not here to absolve anyone, or to assign them works of satisfaction. (Though I’m sure my students think of my tests as a kind of mortification.) But I do think that what we do in theology and history classrooms evokes the first two elements in the sacrament of penance: confession and repentance.

…if the liberal arts are truly liberating arts, they must teach us to be more honest about ourselves, both our personal failings and our participation in unjust systems. If we take them at all seriously, our studies should make it harder and harder for us to lie about the words, thoughts, and deeds (done and undone) by which we — individually and collectively — do not love God with our whole selves and our neighbors as ourselves.

This has important implications for teaching and learning in the humanities. In courses that often center on reading, we should only ask hard questions of our texts if we’re willing to let the texts ask still harder questions of us. In courses that often look to the past, we should not simply judge those who came before us, but let our studies hold up history as a mirror revealing our own shortcomings.

…in the sense that they help us to confess our sins and repent of them, the humanities are penitential. But they are also eucharistic.

Eucharist

…like the Mass, [the liberal arts] provide spiritual nourishment. This comes to mind every other January, when a colleague and I take students to Europe to study World War I, and we end up eating with them every morning and most evenings, figuratively chewing on the questions of the course as we literally chew our food. “Eat this book” is how Eugene Peterson recommended we read the Bible (cf. Rev 10:9-10). And I think we often take a similar approach to the many types of texts that we humanists don’t just consume, but savor.

…And perhaps Christ himself is truly present. I won’t push that eucharistic metaphor any further… but I will quote C.S. Lewis, who once wrote that “every created thing is, in its degree, an image of God, and the ordinate and faithful appreciation of that thing a clue which, truly followed, will lead back to Him.” If you study rigorously any aspect of Creation and its Creator, you should expect to encounter the Living Word, Jesus Christ, the visible image of the invisible God through whom all things came into being (John 1:1-3; Col 1:15).

Ordination

…I hope that all of you find ways to serve the Church. For universities like this exist for the sake of the Church.

That can be hard for some of us on the faculty. I’m so accustomed to examining the flaws and hypocrisies of the Church as revealed in the past that I walk into worship every Sunday cued up to spot similar flaws and hypocrisies being revealed again in the present. I’m sure it’s even more exhausting for your professors who study the Bible and theology and know how badly churches sometimes teach and preach God and his word.

But the Christian liberal arts are Christian in part because they serve the Church and further its mission. We ask questions of the Church, challenge assumptions of the Church, and propose solutions to the Church — for the good of the Church. And we prepare students like you to do all of that, and to serve the Church as you are gifted and called (whether clergy or laity).

Whatever else you hear tonight, hear this: the Church needs you — your questions, your discontent, your gifts, and your passion.

Marriage

For even if you don’t have a pastoral calling, you are still called to specific ways of seeking God’s glory and your neighbors’ good.

Which brings us to… the sacrament of marriage… a sacrament of vocation, a sacrament blessing our use of this present life.

What we teach in our classrooms certainly ought to connect to sexuality and family, but I think there’s a broader objective here: among all the other things that ought to happen as you study the humanities, you should better understand the kind of human God means you to be. This kind of education should help you to recognize, commit to, and prepare for your divine calling from God. For if we follow that vocation, wrote John Calvin, “we shall receive this special comfort: there is no job so simple, dull, or dirty that God does not consider it truly respectable and highly important!”…

Unction

…In its “extreme” form, [unction] is a final blessing on this side of the divide separating mortal existence from what follows. And if our disciplines are about humanity, then they are necessarily about mortality. The kind of education I have in mind should prepare people in the prime of life to encounter the end of life.

But the sacrament (Holy Unction in the Orthodox tradition) is more broadly one of healing and blessing, a way of interpreting James’ admonition to “pray over [the sick], anointing them with oil in the name of the Lord” (5:14). (The present-day Catechism of the Catholic Church calls it simply “anointing of the sick.”)… Our very lives are to be an unction, an anointing of the sick and sorrowing.

So while the humanities can tend to sound bookish and solitary and abstract, any disciplines claiming the name “human” must also foster empathy for hurting humans. And perhaps history, theology, biblical studies, and the others — as much as professional programs in ministry, health sciences, or social work — should prepare us to heal and bless others. They should make us ready to be God’s answer to one of Augustine’s most famous prayers: “Tend your sick ones, O Lord Christ. Rest your weary ones. Bless your dying ones. Soothe your suffering ones. Pity your afflicted ones. Shield your joyous ones. And all for your love’s sake.”

* * *

It’s entirely possible that I’ve claimed too much for our model of Christian higher education. Maybe all we can really hope to do is prepare employees who are better than average at finding patterns, solving problems, and writing reports. But the longer I teach at Bethel, the more convinced I am that there’s more to the Christian liberal arts in general, and the humanities in particular.

So, if nothing else, I hope that thinking of our disciplines in terms of sacramental similes prompts you to consider how God makes ordinary intellectual labors like research, writing, teaching, and learning into means of grace. I hope you’ve listened and wondered if the passion and purpose, doubts and convictions that you recognized in yourself as a young scholar are undeserved gifts of a God who wants his people to love him with their minds, and their neighbors as themselves.

As you leave this place and continue your education, may you consider anew how our disciplines disciple us as followers of Jesus. May your studies open your eyes to the presence of our Christ, till you too, like the disciples of Emmaus, realize that your heart has been burning within you and you rush out into the night to tell a weary world with word and deed the good news of his resurrection (Luke 24:28-35).

May you go in peace and — through your learning and your living — serve the Lord. Thanks be to God.

The complete version of this talk can be found at The Pietist Schoolman.