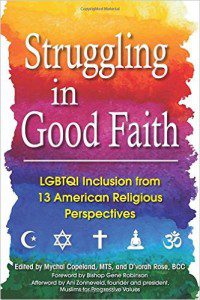

I don’t often do full fledge reviews of book anymore, but recently I received a copy of a soon to be released book from Skylight Paths Publishing called “Struggling in Good Faith: LGBTQI Inclusion from 13 American Religious Perspectives” and have found myself both grateful and perplexed by much of what I have found in this book.

of a soon to be released book from Skylight Paths Publishing called “Struggling in Good Faith: LGBTQI Inclusion from 13 American Religious Perspectives” and have found myself both grateful and perplexed by much of what I have found in this book.

First, let me start with the positives. This book offers a brief theological overview of the case for full inclusion from many American religious traditions that those of us in the dominant Christian, Muslim, or Jewish traditions might not be familiar with, such as the First Nations, Buddhist, Mormon, and Hindu perspective. These brief, easy to understand summaries give the reader a unique glimpse into the religious beliefs that undergird many of these traditions and challenge us to think about some of our own theological beliefs in a fresh perspective.

The editors of this book were also clearly intentional about pulling together a number of diverse voices, including many women and people of color, to represent these American Religious traditions, which I find to be both encouraging and representative of the changing demographics of the American religious landscape in general.

But beyond the accessibility and diversity of this book, there are a number of problems that leap out from the very beginning. First, the breakdown of American Christianity is perplexing and problematic. The editors chose to break down the American Christian church in the following way:

- The Black Church

- Mormons

- Episcopal (ECA)

- Lutheran (ELCA)

- Presbyterian (PCUSA)

- Protestant Evangelical

- Catholic

I find this breakdown to be perplexing for a number of reasons. First and foremost, monolithically describing the “Black Church” as one singular tradition seems to do a great injustice to the amount of texture and diversity among traditionally African-American denominations. Though the author, Minister Rob Newells, clearly states “it is virtually impossible to make generalizations about the lack church without being able to cite significant exceptions…” he continues by saying, “there is still a sense that all black congregations and denominations respond to the same external circumstances and share common internal strenghts, pressures, and tensions.” (Newell’s, pg.2) Whether or not that sentiment is true, it is disappointing that more time was not spent exploring individual African-American traditions and how they have responded to the question LGBTQI inclusion in various theological ways, like was done for other denominations in the book.

The breakdown of American Christianity into Black, Lutheran, Episcopal, Presbyterian, Evangelical, and Catholic is also an interesting choice by the editors. While obviously an entire book could be devoted to the various Christian traditions responses to the question LGBTQI inclusion, choosing these particular denominations, some of which share nearly identical theologies, is confusing to me. Why not break down Christianity into more general camps instead of the almost random breakdown of a few denominations that occurs?

Now for a word on the chapter about my tradition, Evangelicalism: In the chapter on Protestant Evangelical Traditions, the author, Ryan Bell, also seemed to be an interesting choice to author the essay. Though I enjoy Bell’s writings and think he grasps a general understanding of the history of evangelicalism in his chapter, Bells perspective is not the most representative of Evangelicalism today. Bell now identifies as non-religious and his former religious tradition, Seventh-Day Adventism, holds many beliefs that are not in line with what a majority of U.S. Evangelicals believe today and fall outside of what most Evangelicals would consider to be “evangelical”, based on beliefs in extra-biblical revelation, modern day prophets, and untraditional views on eschatology. A chapter could have been written about Seventh Day Adventism alone, which would have been intriguing, but to try to jumble that together under “Protestant Evangelical Traditions” seemed to be quite a stretch, ignoring the great nuance of the various theological positions and denominations that make up evangelicalism today.

I cannot comment on the accuracy of the other theological perspectives represented from non-Christian traditions, but the breakdown of American Christianity gives me great pause in using this book as a resource to help my fellow Christians understand the landscape of the LGBTQI movement among Christians in America.

At risk of sounding overly critical, I do want to reiterate that for the average progressive person of faith who is seeking to grasp a surface level understanding of various religious positions on LGBTQI inclusion in America, this book serves as a tremendous resource and is a welcomed addition to the literature currently available. But as for in-depth theological, traditional, and demographic accuracy when it comes to the nuances of American Christianity, I question the reliability of this book as a resource to to the Christian community.

So, if you’re looking for a brief, progressive overview of positions on LGBTQI inclusion, then this book is for you. But if you’re looking for the depth and nuance that is so crucial to understanding the positions of most religious traditions, this book may leave you wanting.

“Struggling In Good Faith” is Edited by Mychal Copeland and D’vorah Rose and is available wherever books are sold.