by Dale McGowan

It’s easy to get your own story wrong. Selective memory takes a messy life and creates a narrative — a winding path, but one that in retrospect was always bringing Odysseus to Ithaca. And you’d swear it’s a documentary.

For years, the movie in my head of my own road to religious disbelief started with a clear establishing shot — me at 13, staring into the open casket of my father. I always said his death was the event that hit me between the eyes with the God question. Not because I was “mad at God” for taking him away: I loved my father, but it would have been perverse to blame God for killing a three-pack-a-day smoker. I was overwhelmed with grief, but also with a consuming curiosity, one I’d never felt before with such heat. “My Dad” was clearly not in that casket. So where was he?

As the lid was slowly lowered, I swore through my tears to learn the truth. That was the precise moment my intellectual journey began, the one that led me away from the myth of God and toward reality.

Or not.

As it happens, that isn’t the only scene I recall from that week — and another one vetoes the casket epiphany.

I’d spent the previous day avoiding hugs from the murmuring relatives who filled our home. At one point I ducked into my bedroom, a gambit that couldn’t possibly work. I knew someone would notice the missing son and head off on a seek-and-console mission.

Sure enough, as I was reading on my bed, a voice from the doorway made me jump.

“Oh Dale.” It was Aunt Dar, my dad’s older sister, her face contoured with sadness. When she saw the book in my lap, her eyes lit up. “Oh, that’s wonderful! I’m so glad to see you reading that. There is no better place to turn in times of trouble.”

It was the Bible.

What she didn’t know is that I had not turned to the Bible for comfort. I was reading it skeptically, working my way from cover to cover. One way I know this is the wave of guilt I clearly remember crashing over me when she praised me for reading it.

I don’t know quite when I started, but what happened next tells me it wasn’t set in motion by my dad’s death, much less the funeral.

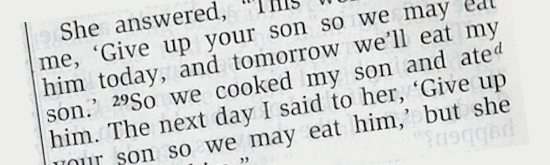

Dar walked to my bedside, glanced at the page I was reading, and gasped. “Oh no dear, not the Book of Kings. Not now. Not that.” She was right, of course. You won’t find much from First and Second Kings embroidered on little pillows. Every five minutes, children are slaughtered by bears, or beheaded, or cooked and eaten by their mothers.

She took the book gently, flipped to Psalms, patted my shoulder, and left the room, click click click, knitting her own happy narrative.

See the problem? Nobody starts reading in Kings. Like most people, I had started with Genesis. I was hundreds of pages into my first full read-through of the Bible by the time Dad died. And even if his death had been the impetus for my questioning, there’s no way I’d have already found enough time alone to get to Kings.

Poking further back, I find more credible catalysts for my early questions. I loved Greek and Roman myths when I was a kid, which led me to wonder what was so different about the more current versions. I read the story of Perseus — in which a god impregnates a virgin, who gives birth to a son who narrowly escapes death, then grows to be a great hero and savior of his people — around the same time I first heard the story of Jesus. I read twice about an infant boy who was hidden in the wilds, then found and brought to a palace to be raised by a king and queen — first Oedipus, then Moses.

I had also developed a crucial attitude: I’d fallen in love with the world. By reading Carl Sagan and others, I’d come to the conclusion that the universe was wonderful, period, and that I was incredibly fortunate to get a chance to be a conscious thing in the midst of it. The wonder of it came with no conditions, no “ifs.” I had become unconditionally smitten with reality long before Dad died, and at some point started working on whether God exists.

If I had any predisposition, it was the usual human one: a desire that it all be true. How could I have stood at that casket and wished for anything but the existence of God, since that might continue the existence of my father? But I knew my preferences were irrelevant. I’d be fine if there was a God; I’d be fine if there wasn’t. I just wanted to know.

In short, I took the question seriously.

Adapted excerpt from “The Unconditional Love of Reality” by Dale McGowan, in 50 Voices of Disbelief, ed. Blackford and Schuklenk (Wiley-Blackwell). Images © 2015 Dale McGowan.

DALE McGOWAN is the author of several books from the nonreligious perspective. He was Harvard Humanist of the Year in 2008 and founded the humanist charity Foundation Beyond Belief in 2010.

Dale is now Content Development Editor and Atheist Channel manager for Patheos. He lives in Atlanta.