Religious Normation and its Consequences for the Civil Rights of Atheists

By Petra Klug, Dept. for the Study of Religion and Religion Education, University of Bremen

The United States has always been a pluralistic but strongly religious country. Religion creates power relations, particularly where it is implemented in political systems or where majorities stand against minorities. I call that religious normation, which means that a society is formed through and influenced by religious norms. This normation was historically particularly notable for religious minorities and for those who are not religious.

But while religious minorities in the long run were included in the American civil religion, atheists are still the least liked minority. The US established a system of religious tolerance that was inclusive of all kinds of religious expressions, but often explicitly excluded atheists. For a long time atheists were not considered citizens, allowed to vote, or to hold office. Though several states still have laws on the books barring atheists from holding office, these are unenforceable. Regardless, they are still unlikely to get elected or to make their voices heard in the political process. This article gives a short historic overview of the forms of this religious normation within the public and political sphere as well as its consequences for the civil rights of atheists from the beginning of the North American colonies to the US presidential election in 2016.

A Country Founded on Religion, and its Nonreligious Other

The American founding myth is that of a country to which religious minorities fled from religious persecution in Europe. The Mayflower Pilgrims and their journey might be the most iconic part of the early history of today’s United States.

In 1620, a ship disembarked in what was about to become Plymouth, New England. Those passengers who went on this journey for religious motives were Separatists—Protestants for whom the Anglican Church’s break with Catholicism did not go far enough, and who demanded their autonomous congregations. When they left for the New World, these Pilgrims interpreted their journey in Biblical terms, seeing themselves as the New Israelites in a covenant with God—an idea that has shaped the United States like no other.

While still on the ship, all male passengers signed the “Mayflower Compact,” agreeing to form a civil body of politics and pleading submission and obedience to the laws of the new colony. But civil did not mean secular here. John Cotton, one of the most important theologians of Massachusetts, describes the system of the colony as a “theocracy” which he found is “the best form of government.”

This idea of the covenant is also described by Massachusetts governor John Winthrop as “a city upon a hill.” The phrase is taken from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount in which he tells his people that they are the light of the world (Mt 5:14). In his sermon, Winthrop urged the unity of the group. The people have to be like one body in Christ, “knitt together […] as one man”, each one having their place. Some are rich, some are poor, but all must obey the same laws. Transgression, “to embrace this present world and prosecute our carnall intentions, seeking greate things for ourselves and our posterity” was seen as a threat to the community as it provokes the “wrathe” of God.

In this religious climate, it was inevitable that the Massachusetts Puritan authorities, together with the righteous members of the community, would choose to oppress people who did not obey their religious norms. Their civil liberties were strictly limited, and deviance from the dominant religion was persecuted. This did not only impact atheists and those who did not attend church, but also religious minorities and nonconformists like Roger Williams, often called the “Father of American Baptism”, who was banned from the colony. Some Quakers were hanged. And as “Papism” was perceived one of the major threats, Catholics avoided the colony. Later in the century, this paranoia (paired with misogyny) escalated in the Salem Witch trials, where 20 people, mainly women, were killed because they were accused of witchcraft.

Not surprisingly, those who explicitly did not believe in God are difficult to trace in this Exodus-story. But even among the Mayflower settlers, by no means all were “Saints,” as the religious pilgrims were called. The bigger part of the settlers, the “Strangers,” were on the ship as merchants, servants, or as people who were sent away from England, which used the colonies as a dumping ground for unwanted individuals. The Strangers were irreplaceable for financing the voyage and for the welfare of the colony. But because of the Puritan influence upon both American history and today’s construction thereof, nonconformist individuals were not just banned from the colonies but also from historical memory.

One of them was Thomas Morton. He and his companions were unwilling to live according to the rules of the Saints and established their own settlement. Although it was named Mare Mount, in historiography it is usually referred to as “Merrymount,” due to the Puritan condemnation of the behavior of its inhabitants. Bradford called it “a schoole of Athisme” and loathed not just their trade with the Indians but also their drinking, dancing and interaction with Indian women. The Puritans could not tolerate such a lifestyle, and destroyed the colony. Morton was arrested, abused in captivity to the point of near-death, and deported back to England.

The strictness of the church was also oppressive for many of the children of the colonists, who were born into this religious structure whether they wanted to be a part of it or not. There were special covenants that allowed them to be “half way” in the churches. But if you did not belong to a church at all, your civil rights were severely curtailed. In terms of political and public participation, atheists were restricted in their status as citizens, in their freedom of expression, in their franchise and in their rights to hold public office.

Opposition towards this exclusion was persecuted. When, for example, a group of men around Robert Child and William Vassall complained in a petition that English men who are not members of the established Puritan churches were not allowed to vote or to hold office and demanded their civil liberties, they were in turn arrested and sentenced to pay heavy fines. According to the laws of Massachusetts, Atheists and Blasphemers were imprisoned, had to sit in Pillory, were whipped and had their tongue burned “with a red hot Iron.”

Given this rigid religious normation of the political sphere, the public space and private life conduct, it appears that the religious non-conformists that fled from Europe to the New World sought religious freedom only for themselves.

The godless Constitution and religious liberties

Some of the restriction for atheists and religious minorities were resolved through the Constitution and the First Amendment. The Constitution does not mention God or a creator. Instead, it starts with “We the People of the United States” and says explicitly that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust.”

But that was actually not primarily a concession to the nonreligious. In eighteenth century America, the experiences of religious persecution by the establishment made the idea of a secular state also desirable for religious dissenters. The metaphor of a “wall of separation” is often accredited to Thomas Jefferson, who was under permanent suspicion to be an atheist himself. But Baptist Roger Williams, who once was banned from Massachusetts for his dissenting views, wrote already in 1644 that only the “wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world” could make the purity of the church possible. So, secularism as the separation of church and state during the time of the founding of America was as much in the interest of the nonreligious as in that of the religious dissenters.

In the ratification debates within the states, the omission of God caused a lot of discussion. Many commentators were critical of the absence of a religious test in the Constitution: One delegate in Massachusetts pointed out that, although he hoped to see only Christians in office “by the Constitution, a papist, or an infidel was eligible as they.” A North Carolina delegate feared that the lack of a religious test was an “invitation to Jews and pagans,” and one of his colleagues extended that fear to Papists and Muslims. Nevertheless, in the end the religious and nonreligious concerns that the possible establishment of a state church would endanger their own freedom, prevailed.

In order to further protect their religious liberty, the States called for the addition of ten amendments to the Constitution: The First Amendment acknowledges that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”—usually called the Establishment Clause and the Free-Exercise Clause. But even in those states that have been traditionally open to religious minorities, neither the Establishment Clause nor the idea that no religious test should be required seemed to be understood as a protection for nonbelievers. In many of the states’ constitutions we find paragraphs that explicitly prevent atheists from holding office. The Constitution of Maryland, for example, establishes “That no religious test ought ever to be required as a qualification for any office or profit or trust in this State, other than a declaration of belief in the existence of God.”

It took until 1961, when Roy Torasco, who was appointed Notary Public in Maryland but was denied office because he did not declare his belief in God, took his case before the Supreme Court, that this was ruled unconstitutional: The religious test violated the First Amendment because the state’s power and authority “is put on the side of one particular sort of believers – those who are willing to say they believe in ‘the existence of God.’”

The enemy from without and the enemy from within

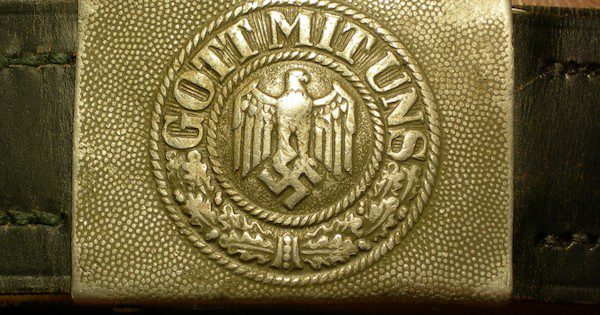

But even after the civil rights of atheists were more or less fully established, that did not make atheists accepted citizens in the US. During the wars and conflicts of the twentieth century, atheism was frequently associated with the enemy—be it the enemy from outside, or from within. In the First World War, atheism was associated with the Germans, who were accused of starting the war because they no longer believed that Jesus was the son of God, although Germans were as convinced as their opponents that God was on their side. In the Second World War, atheists were associated with the Fascists who set up Hitler as their new God and wanted to destroy all religion, despite the fact that Hitler himself had atheists persecuted. In order to convince Americans to participate in the war, Roosevelt presented the Nazis as a threat to Christianity:

Nazis have now announced their plan for enforcing their new German, pagan religion all over the world—a plan by which the Holy Bible and the Cross of Mercy would be displaced by Mein Kampf and the swastika and the naked sword.

Atheists were also associated with Anarchists and Communists—and during the First Red Scare many of them were deported from America to the godless Soviet Union. During the Cold War, the international struggle was stylized as a battle between Communism and Christianity. Billy Graham voiced the concerns of many when he declared: “The heart of man is so designed that it must embrace some sort of religion; if it cannot bring itself to accept the true gospel of Christ, it invariably embraces some kind of false ideology.”

However, despite the Protestant dominance, a new sense of ecumenism has emerged since the eighteenth century. Against the threat of atheism and godlessness, the formerly much-feared religious minorities slowly got included in an extended concept of Americanism. In the middle of the twentieth century the American civil religion was broad enough to embrace Protestants, Catholics, and Jews through the all-encompassing notion of a belief in God. In the 1950s, “One Nation” was complemented with “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance, and the national motto was changed from “E Pluribus Unum” to “In God We Trust.” Therefore, to be an American by definition meant being religious. Atheists and other people who did not believe in God were, if not legally, at least symbolically excluded from American citizenship.

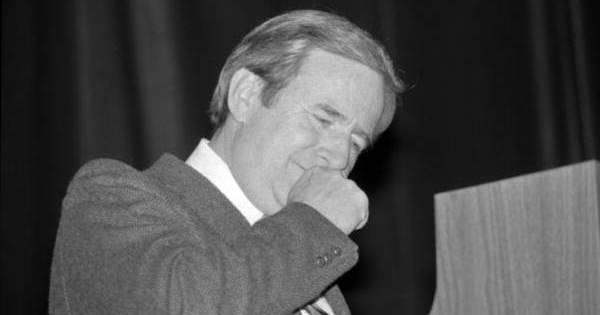

With the election of John F. Kennedy, America had for the first time a Catholic president. In order to temper Protestant American’s century-old fear of Catholics, Kennedy displayed a strong commitment to the separation of church and state. He reminded his voters that this belonged to the founding principles of the United States and was first erected in order to protect the Protestant minorities. But although not an eager churchgoer himself, his dedication to the separation of church and state ended where it was about those who did not belong to a church at all: “I believe in an America,” he stated, “where religious intolerance will someday end – where all men and all churches are treated as equal – where every man has the same right to attend or not attend the church of his choice.” Here, he gave no fodder to his opponent Richard Nixon, who is quoted saying: “There is only one way that I can visualize religion being a legitimate issue in an American political campaign. That would be if one of the candidates for the Presidency had no religious beliefs.” So, even at a time when America was more tolerant than ever before, this religious tolerance was not extended to atheists.

Instead, I would argue that atheists were often the negative against which the new pluralistic religious unity was built. This interdenominational exclusion of atheists culminated in the rise of the religious Right in the 1980s. The so-called “Culture Wars” were not struggles between different religions or denominations anymore. In fact, the more conservative parts of the various religious groups united on the basis of their jointly held religious norms, which they wished to impose on the Liberals and the Godless, whether they shared these values or not. The causes for alarm and regulation might have changed since the founding years—from drinking, dancing and interracial intercourse to homosexuality, abortion, and birth control—but it was still an attempt to religiously limit individual behavior that was at odds with religious norms.

In 2001, after America was attacked by Islamic fundamentalists, conservative politicians like president George W. Bush or New York major Rudy Giuliani spoke at interreligious prayer meetings, which included Muslims but were—as prayers—by definition not inclusive of atheists. Conservative preachers like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson even got out the old covenant idea and interpreted terrorism as a punishment from God. Falwell blamed the attacks on pagans, secularists, and everyone who violated conservative religious norms: “I point the finger in their face and say ‘you helped this happen.’”

So, after over 400 years, atheists are still seen as a threat and used as a scapegoat— even for religious violence.

Still “God’s own country”

It was not until Barack Obama’s Inaugural Address that a president acknowledged that the United States is “a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus and nonbelievers.” But how much of an impact did that have? If we look at the 2016 election, polls show that atheists are still extremely unpopular. Asked by pollsters, 40 percent of Americans would not vote for a generally well qualified person, nominated by their own party, if he or she were an atheist. This disdain is only exceeded by that for socialists—who are, of course, usually also atheists. So, 55 years after Roy Torasco fought for an atheist’s right to hold public office, atheists still have virtually no chance of being elected President. And their odds aren’t much better on other political levels. Currently, there is only one member of Congress, Kyrsten Sinema, who is not affiliated with a religious group—and she would not call herself a nonbeliever.

But elections do not only consist of candidates. They also include voter groups and their interests. In the 2016 election, polls suggest the unaffiliated will overwhelmingly vote for Democrats, by a much wider margin than mainline Protestants or white Catholics, for example. Although being unaffiliated or a religious “None” does not necessarily mean being atheist, many Americans are in fact nonreligious. In 2014, seven percent of the US population identified as atheist or agnostic—and their numbers are growing. That actually makes them one of the bigger voter groups. For comparison: The other three religious minorities, that Obamas mentioned in his Inaugural address—Muslims, Jews and Hindus–count for only 3.5 percent together!

For a number of years, atheists have also tried to make themselves heard as voters, for example by wearing T-shirts that state “I am an atheist and I vote.” And yet atheists are barely addressed as a group to reach out to. When Hillary Clinton was asked by the lobby group “Atheist Voter” what she thinks about religion based policies that are discriminating for some people, she said: “Well, look, I think we’ve gotta stick with our founding principles, separation between church and state. And remember: It was done in the beginning mostly to protect religion from the state. So we need to stick with what has worked.”

After being excluded from American politics for over four centuries, sticking “with what has worked” can’t be too satisfying for atheists. And many of them will also have noticed that Barack Obama only mentioned them after he got elected. Atheists still seem to be untouchable for politicians, even as the Democratic Party competes for their vote with the Libertarian and Green Parties. The growing percentage of atheists could make a significant difference in American elections, given the tight margins that typically exist between the two major parties. So the question remains, what drives this indifference towards atheists as a political group? Why are parties and candidates so hesitant to reach out to them?

According to the “Atheist Voter,” their major political concern is “upholding the constitutional principle of separation of religion and government.” Separation of church and state is a principle that greatly helped religious minorities to be accepted in the broader society. According to the above mentioned poll, over 90 percent would vote for Catholics or for Jews, and over 80 percent for a Mormon. And even Muslims—who are under constant attack since 9/11 and who Donald Trump wants to deny citizenship—score better than atheists. Religious minorities have long-lasting relationships with political parties. Religious tolerance and interfaith prayers are an established part of the American political makeup.

But as inclusive as this American civil religion might be, it can never be inclusive for atheists. Difference in terms of religion is accepted, exactly because of its shared recognition of God or at least some sort of afterlife judgement. The religious and atheists don’t just differ on concrete political issues like the rights of women and homosexuals, scientific progress, and tax policies that favor religious groups. In my research, I have discovered that they differ on a much more fundamental level. They display unevenness in what they consider the truth and what legitimate sources of knowledge are, the justifications of morality, appropriate modes of human interaction, the rules of conduct they find binding, their ideas about the formation and organization of the world, as well as their views on the meaning of life.

Based on these fundamental differences, atheists are seen as a threat to a religiously normated version of American. They are not accepted as just another variation in the discussion of beliefs that can be tolerated in a pluralistic America and protected by a state which is separated from religion. Paradoxically, the extension of religious tolerance towards religious minorities has not minimized but fostered the exclusion of atheists. They are not allies for a common cause anymore, but are singled out as the one group that still differs. Their political demands for the removal of compulsion in matters of church and state as it exists for example in the Pledge of Allegiance, is not seen as the legitimate demand of a minority, but as an attack on religion itself. Therefore, openly embracing atheists for the political parties might risk the votes of all religious voters, even those that historically favored the separation of church and state.

If political power and the unity of the country continue to be sought through religious inclusion, atheists will stay at the margins. For them, America is still “God’s own country.”

PETRA KLUG obtained a Masters degree in Sociology and Cultural Studies, as well as a Masters degree in the Study of Religion, from University of Leipzig. A recipient of the dissertation scholarship of the German Research Foundation and current Research Associate at University of Bremen, she is completing her dissertation on the religious normation of atheists in the United States.

PETRA KLUG obtained a Masters degree in Sociology and Cultural Studies, as well as a Masters degree in the Study of Religion, from University of Leipzig. A recipient of the dissertation scholarship of the German Research Foundation and current Research Associate at University of Bremen, she is completing her dissertation on the religious normation of atheists in the United States.

All post images public domain via Wikimedia