“Think, dear sir, of the world you carry within you, and call this thinking what you will; whether it be remembering your own childhood or yearning toward your future—only be attentive to that which rises up in you and set it above everything that you observe about you.”

–Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, Letter Six

Puddle Apocalypse: In Praise of Forgetfulness

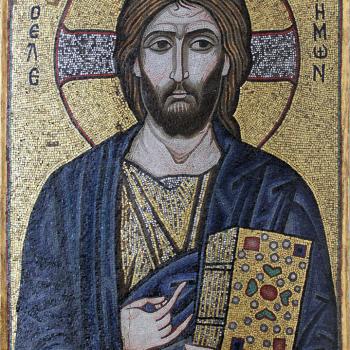

As solstice approaches, and I meditate on Advent in an online course with Rebecca Bratten Weiss and Jessica Mesman Griffith, I am drawn to the idea of “rending the veil.” As Rebecca recently wrote in a lovely essay on her blog, “We’ve forgotten, after all, that ‘apocalypse’ does not, technically, refer to things blowing up and keeling over, nor even to ‘end times stuff’ – but rather to revelation. Literally, the lifting of the veil. That which was hidden from the foundation of the world is made present to us. Reality rushes up, right at us, right in the face.” A friend is preparing to have surgery next week, and I told her I would write in December to make up for writing she can’t do at the moment. I will pick up that thread. But what am I to write about, in the face of the truths of illness and surgery, in the face of the social climate in which we live? What do I make of the truth that is eagerly “rushing up … right at [my] face,” as Rebecca put it? And how am I to make room right now for the silence in which grace can enter?

*

When I was a graduate student in Philadelphia, I lived in a studio apartment in a brownstone at 20th and Spruce, and in my off time, I wandered around the city keeping myself company by watching pigeons and trees and people. One of my favorite activities was to take a walk at dusk and look into the finely appointed homes of wealthy people who had not yet closed the blinds, before climbing the three flights back up to my studio apartment to perch on my futon couch and study the tree out my back window. In winter, the sidewalks in the neighborhood were never shoveled, and pedestrians’ tread merely wore a trough down the middle of the icy surface as the snow partially melted and re-froze. One afternoon, as I made my way back home, the spool of thought unwinding in my head caused the movement of my body to wind to a halt. And there I stood, standing and staring into a puddle, lost in thought.

I had paused in the middle of a block in front of an alleyway—the puddle of choppy ice and water was indeed daunting. Probably what had happened was my thoughts had been interrupted by another momentary thought—“How do I get around this puddle?” This thought had been followed by study of the puddle, and perhaps then followed by interest in the look of the puddle, at which point my mind picked back up on its previous thread, whatever it had been. Maybe I was thinking about a poet friend who was about to become, for a time, my lover. Or maybe I was thinking about a book or writing a poem in my head. I don’t remember. That afternoon, I only realized I was stuck in front of the puddle when a car slowed, then paused next to me, the driver partly unrolling the window to ask if I needed help. (I must have looked so odd, standing and staring for the entire time that it had taken the person to drive down the block toward me.) I was startled then, and, I have to admit, filled with a wave of interest and amusement in myself, in the character of me who could come to a complete stop in front of an icy puddle on a freezing winter afternoon and lose track of the fact that I had been walking. I don’t remember if the driver was a man or a woman. I believe it was a person of middle age and benign countenance who possibly had a daughter or niece or student my age. I laughed and thanked the person, then waited for the car to pass before clumsily skirting or vaulting over the water.

So, where does grace enter? The answer, I think, lies in letting go the thread of narrative drumming through our American heads, one that drives us toward measuring ourselves only in terms of external success. As Muriel Rukeyser wrote in The Life of Poetry, “In art, of course, the mysticism of success and failure will not hold. The world of business is open warfare, cold iron through every throat, and the battle-shriek ‘Success!’ But in art, these terms cannot apply.” Whether artist or not, there is comfort to be found in the dark corridors of one’s own mind. On and off since childhood, I have been followed by what Churchill called the black dog, a sadness that slows me down, a dark sludge moving through the body. That isn’t the darkness I’m referring to here, but rather one that has run alongside it, a pensiveness tinged by melancholy that does not pull me down, but carries me along on a stream of spirit—what a boyfriend in my 20s referred to as my “only child syndrome”—an ability at times to be utterly content in my own mind, following threads of thought. “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life.” And if I’m lucky, the melancholy forgetfulness of that young poet I was, wandering alone, losing myself into grace.

Joanna Penn Cooper is the author of The Itinerant Girl’s Guide to Self-Hypnosis (Brooklyn Arts Press), a book of lyrical shorts, and What Is a Domicile (Noctuary Press), a book of poems. She lives in Durham, North Carolina. She curates the “Approaching Mystery” series for Sick Pilgrim, publishing flash essays by writers encountering the unseen, the uncanny, and the unresolvable.