I’m not sure this is a book.

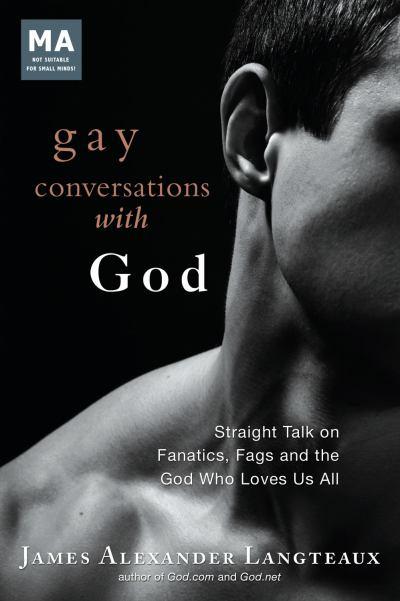

It’s in book form, mostly — type is set on pages in a binding, words on paper — but it reads more like the transcription of a one-man show. In Gay Conversations With God, James Langteaux gives us a spoken-word performance, with the rhythm and rhyme of speech. The cadence and wordplay and oddly laid-out parenthetical comments all make me want to see and hear that one-man show.

I suspect, then, that this book would work best as an audio book read by the author. Or, rather, as an audio book performed by the author, since that’s what we have here, a performance.

It’s an entertaining performance. Langteaux is charming, charismatic, sometimes moving and sometimes very funny. He can be both self-deprecating and self-aggrandizing, both painfully honest and defiantly defensive. He can be engaging, exhausting, amusing, infuriating, profound, profane, affectionate and abrasive, inviting and off-putting — frequently all at once in a single anecdote.

It’s an entertaining performance. Langteaux is charming, charismatic, sometimes moving and sometimes very funny. He can be both self-deprecating and self-aggrandizing, both painfully honest and defiantly defensive. He can be engaging, exhausting, amusing, infuriating, profound, profane, affectionate and abrasive, inviting and off-putting — frequently all at once in a single anecdote.

I like him. He works so hard to be liked that it would seem churlish not to. I enjoyed the show.

But I also worry about him. I’m left, at the end of this performance, wondering what Langteaux is like when he’s not performing. Or wondering if there ever is a time when he’s not performing — when he allows himself to stop. What is he like when he’s not “on” — not on stage, not on a roll or on a rant or a riff?

The manic persona we meet in this performance can’t be sustained all the time. I wonder if the pendulum may swing to the other extreme when the spotlight is off and the audience has left the theater. Who is James Langteaux on nights like this, when the world’s a bit amiss, and the lights go down across the trailer park? Who is he when the wig goes back in the box?

That last bit is from Hedwig and the Angry Inch. The reference seems apt because Langteaux seems divided in two, split between two worlds. He is a gay man. And he is an evangelical Pentecostal. Langteaux is very gay and very Pentecostal. If there were a Kinsey scale for Pentecostal spirituality, he’d be a solid 6 on that too. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Some of my best friends are Pentecostal …)

He struggles to reconcile these two worlds:

I’ve been a pretty bad Christian and a fairly decent homo for a very long time. But the idea that these two wildly disparate worlds may merge seemed about as likely as Grey Goose sponsoring the Southern Baptist Convention.

Langteaux is flamboyantly Pentecostal. As with much of this book, that can be both off-putting and endearing — and more so of both than his sexual flamboyance because it’s less self-conscious, less intentional. His discussion of his sexuality often has a deliberate “ooh, did I shock you?” quality that can seem more performance than revelation (see, for example, the book’s subtitle: “Straight Talk on Fanatics, Fags and the God Who Loves Us All”). One senses that he’s always aware of how his frank comments may be perceived by heterosexual readers. But when he discusses his intensely Pentecostal spirituality, he seems less aware that this may be strange or unfamiliar to others, making that discussion seem less guarded and more openly earnest.

J.R. Daniel Kirk is probably right when he says that Langteaux’s discussion of sexuality can be “over-the-top in ways that, while probably helpful to those who need the book most from the gay-person-struggling-with-God end of things will no doubt put off most who hold a non-affirming position.” But I suspect the book’s flaming Pentecostal spirituality may also put off other potential readers.

For years, Langteaux was a producer and reporter for The 700 Club. His faith still takes that shape, with all the spirit-filled intimacy, immediacy and intervention it takes as a given. So Langteaux is someone who constantly seeks — and receives — signs from God. God speaks to his heart. He believes in miracle. His testimony includes numerous explicit answers to prayer, and even the classic open-the-Bible-at-random gambit/discipline.

This spirituality — intuitive, visceral, emotional and idiosyncratic — is both a weakness and a strength when it comes to Langteaux’s struggle to reconcile his undeniable gayness with the faith that also defines him. He learned that faith from people like those at The 700 Club — people who see God as vehemently, inviolably anti-gay.

In the world of The 700 Club, God’s hostility to gayness is simply a given. It’s not something that is argued so much as something simply asserted — a self-evident truth endorsed by the sanctified intuition of all spirit-filled Christians. The argument, such as it is, is all pathos.

And for the most part, that is how Langteaux responds — all pathos. As Kirk writes:

As a Bible scholar, I was less than happy with the biblical discussions in the book. But this isn’t an exegetical book, it’s not even attempting a biblical argument for homosexuality. It’s about the experience of finding the God of love.

Experience and intuition are the “heart” at the heart of Langteaux’s plea. We evangelicals are big on hearts. We ask Jesus “into our hearts.” It would be an awkward moment if you stood in an evangelical pulpit and praised God for saving you when you asked Jesus into your mind.

So this book is written from the “heart” — a cri de couer. If you’re looking for a biblical discussion, turn to someone like Matthew Vines. Langteaux is not a Bible scholar. In his 700-Club world, the Bible is one way that God speaks to Christians, but not the only way. God’s side of this “conversation” isn’t mainly scriptural, but comes through more individual direct revelation. In this world of intuitive, spirit-led Pentecostalism, such direct revelation can seem to trump scripture, tradition, reason and experience (the four parts of the “Wesleyan Quadrilateral”).

That’s the trump-card that Langteaux’s former colleagues at The 700 Club play against him, and the same trump-card that he plays in response. That leaves things at a stand-still. “God showed me.” “Oh, yeah? Well God showed me too.” Pathos vs. pathos.

In places, though, Langteaux’s pathos leans toward something more formal and less subjective. In a breathless retelling of Jesus’ story, Langteaux writes:

[The religious] would never buy into the teachings of a guy who was unwilling to obey the basic laws of the Sabbath — how in the hell could this man be God when he continually chose to over-ride the very rules he had put in place thousands of years before? Rules and laws that these religious men spent a lifetime perfecting, preaching and enforcing. …

To top it all off, Jesus had a new message — it was a message not of rules and laws and dictates but a message of unconditional love and grace.

That points in the direction of something a Bible scholar can work with, although Langteaux himself doesn’t continue in that direction.

Langteaux’s history with The 700 Club involved him, for years, in the promotion of its anti-gay ideology. He was even, for a time, heralded as an example of the kind of miraculous “reparative” spirituality that can pray away the gay. Being a part of that world was damaging for him — damaging for his self-image, damaging for his soul. And, of course, it wasn’t only damaging for him, but also for other LGBT people who heard that anti-gay message, or whose lives continue to be affected by the millions of Christians who have heard and absorbed that message.

Langteaux seems to realize the damage he has suffered, and the damage that others have suffered, but he doesn’t dwell on his own role or culpability in promoting that agenda. As Timothy Kincaid wrote at Box Turtle Bulletin, that makes Langteaux a bit problematic. “When a damaging person comes out,” Kincaid says, he reserves the right to be skeptical.

That suggests another book, I think, that James Langteaux probably needs to write and that others, like Kincaid, certainly need to read. This book doesn’t offer such a mea culpa, but it may be a step closer to that step — the ninth step that Kincaid (rightly) sees as necessary.

But what are we to make of this book? I don’t think it’s likely to be popular or persuasive for those in the church who reject the full affirmation of LGBT Christians. Those folks are always demanding (and then dismissing) a point-by-point refutation of their clobber-verse proof-texts, and Langteaux doesn’t even attempt to provide that.

But perhaps those Christians will, at least, recognize that this is a personal testimony. We Christians are supposed to like personal testimonies (particularly ones, like this, that offer lots of sordid detail). Langteaux’s personal testimony won’t likely persuade such Christians to change their views, but I hope, at least, that it may make them more aware of the consequences of those views and the human toll they take on all sides.

The real audience for this book, though — the people it can and, I think, should reach — is made up of other people like James Langteaux, people caught between these two worlds, undeniably queer and undeniably evangelical. There are likely millions of people struggling to live in that divided state — a population larger than that of the divided city in which poor Hedwig was born.

Some of them will try to pray away the gay but, as Langteaux found out, that never works. And some of them, like Langteaux, may try to gay away the pray — but that didn’t work for him either. He was born this way and born-again this way.

He’s not alone in that. And for many others like him, torn between those two worlds, this messy, off-beat book may be a lifeline and a source of healing.