Mark Twain and Neo-Confederate fossil Loy Mauch agree on one point: The Bible contains many texts that permit, condone, and even command slavery.

They’re both right about that. It does.

They’re both right about that. It does.

But it would be wrong to conclude that, therefore, the Bible as a whole condones slavery. Because the same Bible that offers this “authorization” of slavery in some places also, in other places, demands its end. The Bible both condones slavery and condemns it.

Mauch is as clueless about what the Bible actually says as he is about American history. He falsely claims that slavery is never condemned by “Jesus, Paul or the prophets.” That’s not something he could say if he’d ever read Jesus, Paul or the prophets.

The final chapters of Isaiah, for example, are filled with visions of a world without slavery. In Isaiah 58, the prophet dismisses religious observance as irrelevant without liberation of the enslaved:

Is not this the fast that I choose:

to loose the bonds of injustice,

to undo the thongs of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

Jesus read a nearby passage from Isaiah in his very first sermon, announcing the essence of his gospel of the kingdom of God. Slavery has no place in God’s kingdom:

When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

The reference there is to Jubilee — the end of slavery and debt. Jesus was proclaiming the fulfillment of Jubilee. Even more than that, Jesus was declaring himself to be that fulfillment, declaring himself to be the ultimate, final Jubilee. It’s absurd to say that Jesus never spoke against slavery when he began his ministry with the audacious announcement that he was emancipation personified.

As for Paul, well there’s a long, popular convention of plucking clobber verses out of his epistles — usually from out of the midst of one of his many long arguments against being ruled by clobber verses. Those seeking proof-texts condoning slavery can find them in Paul, but to do so they’ll have to dance around and between other passages where he proclaims that there can be no slaves in Christ or tells his readers “do not submit again to a yoke of slavery.” And Paul can only be declared a defender of slavery by those pre-committed to a perversely obtuse reading of Philemon (about which more later).

But let’s not get sucked into the very thing Isaiah and Jesus and Paul all warned us against — imagining that religion amounts to compiling lists of clobber verses to tell us what to do. If you’re reading the Bible as a collection of clobber verses, then you’re doing it wrong. The point is never to see which side’s clobber verses can out-clobber the other side, but to account for the full context and trajectory of the whole.

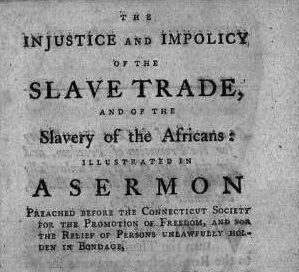

This argument — proof-texting vs. a more comprehensive reading of the Bible — has been going on here in America for centuries. And this argument began in earnest around this very subject: slavery. What the Bible says about slavery depends on how you go about reading the Bible. Long before the Civil War — and even before the Revolution — Americans fought over slavery by fighting over how to read the Bible.

The defenders of slavery settled on the approach to biblical interpretation that best served their purpose (and, not coincidentally, that best served their economic interest). The only way to make the Bible useful in defense of slavery was to treat it as a collection of legal proof-texts. They began isolating and elevating these disparate texts and demanding that they be treated as authoritative. They asserted that this was a literal, obvious and common-sense approach to the Bible (all while desperately avoiding the glaring fact that American-style slavery is nothing like the kinds of slavery described in those passages).

Opponents of slavery sometimes also cited particular texts, appealing to their authority. But generally they took a broader view — invoking not just specific passages, but the great central themes of scripture, the over-arching principles rather than the isolated proof-texts.

Historian Mark Noll has written a great deal about all of this — about how the debate over slavery in America was, for many years, shaped by a parallel debate over biblical hermeneutics. And, he notes, that debate over slavery has continued to shape American biblical hermeneutics more than a century after Emancipation. (See, for example, Noll’s The Civil War as a Theological Crisis.)

There’s an excellent essay of Noll’s online, titled “Battle for the Bible.” Noll begins by describing a theological debate from 1845 between slavery proponent Nathan L. Rice and abolitionist Jonathan Blanchard (who went on to help found Wheaton College).

While Rice methodically tied Blanchard in knots over how to interpret the proslavery implications of specific texts, Blanchard returned repeatedly to “the broad principle of common equity and common sense” that he found in scripture, to “the general principles of the Bible” and “the whole scope of the Bible,” where to him it was obvious that “the principles of the Bible are justice and righteousness.” Early on in the debate, Blanchard’s exasperation with Rice’s attention to particular passages led him to utter a particularly revealing statement of his own reasoning: “Abolitionists take their stand upon the New Testament doctrine of the natural equity of man. The one-bloodism of human kind [from Acts 17:26]: — and upon those great principles of human rights, drawn from the New Testament, and announced in the American Declaration of Independence, declaring that all men have natural and inalienable rights to person, property and the pursuit of happiness.”

Blanchard’s linkage between themes from scripture and tropes from American republicanism was repeated regularly by abolitionists. But this use of the Bible almost never found support in the South and only rarely among northern moderates and conservatives. In general, it was a use that suffered particular difficulties when, as in the ground rules laid down for Blanchard and Rice in their Cincinnati debate, disputants pledged themselves in good Protestant fashion to base what they said on the Bible as their only authoritative source.

Abolitionists like Blanchard moved from “the whole scope of the Bible” to “great principles of human rights,” but as Noll notes:

The stronger their arguments based on general humanitarian principles became, the weaker the Bible looked in any traditional sense. By contrast, rebuttal of such arguments from biblical principle increasingly came to look like a defense of scripture itself.

… Nuanced biblical attacks on American slavery faced rough going precisely because they were nuanced. This position could not simply be read out of any one biblical text; it could not be lifted directly from the page. Rather, it needed patient reflection on the entirety of the scriptures; it required expert knowledge of the historical circumstances of ancient Near Eastern and Roman slave systems as well as of the actually existing conditions in the slave states; and it demanded that sophisticated interpretative practice replace a commonsensically literal approach to the sacred text. In short, this was an argument of elites requiring that the populace defer to its intellectual betters. As such, it contradicted democratic and republican intellectual instincts. In the culture of the U.S., as that culture had been constructed by three generations of evangelical Bible believers, the nuanced biblical argument was doomed.

Noll’s conclusion closely echoes the words of Mark Twain. “The world has corrected the Bible,” Twain wrote. “The Church never corrects it; and also never fails to drop in at the tail of the procession.” Noll sees the same dynamic:

The country had a problem because its most trusted religious authority, the Bible, was sounding an uncertain note. The evangelical Protestant churches had a problem because the mere fact of trusting implicitly in the Bible was not solving disagreements about what the Bible taught concerning slavery. The country and the churches were both in trouble because the remedy that finally solved the question of how to interpret the Bible was recourse to arms. The supreme crisis over the Bible was that there existed no apparent biblical resolution to the crisis. It was left to those consummate theologians, the reverend doctors Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, to decide what in fact the Bible actually meant.