I’m so old I can remember 2013. I mean, like, early 2013. February of that year saw a contentious battle in Congress to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act. The Senate voted to extend the law early in the month — just as that chamber had voted to do so a year earlier — but it took most of the month to get the House of Representatives to do so as well. President Obama signed the reauthorization and extension of the law in early March of 2013.

Maybe you remember this too. It was important because VAWA is important. This landmark legislation has had bipartisan support for more than 20 years now because, as the ACLU put it in 2005: “VAWA is one of the most effective pieces of legislation enacted to end domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking. It has dramatically improved the law enforcement response to violence against women and has provided critical services necessary to support women in their struggle to overcome abusive situations.”

All true. That’s why progressives were unified in 2013 in fighting for the law’s extension, just as they had been unified behind it back in 1994 when the law was first passed.

All true. That’s why progressives were unified in 2013 in fighting for the law’s extension, just as they had been unified behind it back in 1994 when the law was first passed.

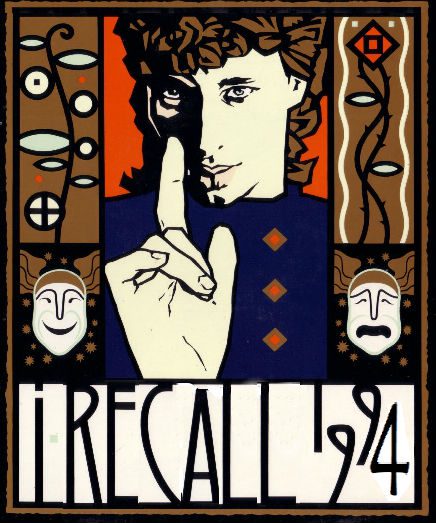

I’m old enough to remember that too. I was something of a bush-league para-church lobbyist back then. Our organization didn’t have a lot of clout, but we used whatever influence we had to advocate for VAWA and we celebrated when it was signed into law on September 13, 1994, by President Bill Clinton.

I’m proud of that. We predicted at the time that VAWA would have a substantial impact in protecting women from violence and abuse. And we were right. It did. It changed the world for the better.

But fighting for VAWA back in 1994 didn’t make our little outfit exceptional. This was something that every progressive group was supporting at the time. Just like during the reauthorization fight three years ago, progressives were unified behind VAWA in 1994.

Today, though, the unity of that 2013 VAWA reauthorization battle seems like a distant memory. Today, I’ve been told, that anyone who supported VAWA in 1994 is history’s greatest monster.

How did that happen? Well, we’re in the middle of a substanceless primary purity argument* centered around the 1994 Biden Bill — the omnibus crime bill that included VAWA. That argument never mentions VAWA, or any of the many other laudable ingredients in that sprawling, throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks legislation. That law was the product of political compromise — so it included things progressives loved (like VAWA and the assault weapons ban) as well as many other things that conservatives loved and progressives hated (grants to states to build prisons), but that progressives accepted to because that’s how divided government works. But the law was also a mixed bag because it was stuffed with trial pilot programs and untested new ideas. Some of those turned out to be good ideas. Some fizzled out fecklessly.

But the current argument over this law completely ignores most of what this legislation did or attempted to do. The current argument is focused exclusively on the Gingrich parts of the Biden Bill — the elements of the law that the Republican-controlled House demanded as the price for their support.

Those elements were cause for concern back in 1994. Progressives weren’t happy about them — that’s why it’s called “compromise.” But the overall sense at the time among progressive constituencies was that these bitter Gingrichian elements didn’t outweigh the necessity and urgency then requiring the more Biden-y bits to be passed.

After all, this wasn’t the kind of “law-and-order” crime bill that House Republicans were demanding. I was in Philadelphia in 1994 during the debate and push for this law. Frank-Rizzo types opposed it because they didn’t see it as their kind of get-“tough”-on-crime legislation. Philly’s powerful black clergy did like it because they saw it as having the potential to make their constituents’ safer — they saw it as recognizing that black neighborhoods matter.

Mark Kleiman provides some important context for how this bill came to be. Click through that link to read his extensive discussion of that context and background — that’s important. Here I’ll excerpt Kleiman’s discussion of the mixed-bag of the law’s actual substance:

That bill was a mix of provisions, including, as usual, the good, the bad, and the ugly. Some of what seemed good at the time to progressives actually hasn’t turned out to be of much use; some of what seemed bad at the time to progressives (especially “100,000 cops”) has turned out to be hugely beneficial to poor minorities living in big cities; and much of the ugly stuff just hasn’t mattered, though the really ugly prison-building provisions mattered a lot. …

The thing the president and his advisers really seemed to believe in was carrying out his campaign pledge to put “100,000 new cops on the beat” by providing federal money to hire local police officers.** But given the apparent uselessness of just adding more resources to a system that didn’t know what it was doing, the administration added a twist: to get the money, departments had to commit — at least on paper — to implement “community policing” to move departments away from the demonstrated futility of the random-preventive-patrol-plus-rapid-response-to-calls-for-service model that had dominated the “reform” style of policing since the 1920s.

Since then, of course, crime has fallen dramatically; the extent to which the crime bill’s contribution of more cops and encouragement of new policies contributed to that fall is subject to dispute. Massive social trends tend to be over-determined, and no one at the time the bill passed predicted the spectacular crime decline that ensued. But it’s worth noticing that most of the explosion in incarceration for which the bill (and President Clinton as its sponsor, and Hillary Clinton because her last name is “Clinton”) get the blame occurred before the bill became law, while virtually all of the decline in crime for which neither the bill nor either Clinton gets any credit came after the bill’s passage. …

In addition to “100,000 cops,” the bill was a grab-bag of programs popular with liberals or conservatives: VAWA (a good idea, later partly gutted by the Supreme Court), the assault weapons ban (mostly an irrelevancy because few murders involve “assault weapons,” however defined, and because the definition of “assault weapon” in the law allowed functionally equivalent firearms to continue to be sold), federal “three-strikes” legislation (again mostly an irrelevancy because the federal system holds only about a tenth of the nation’s prisoners), 41 new capital punishment crimes (none of them ever used; the federal government has executed only three people since the law passed: Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and two other murderers); a really nasty provision denying educational grants to prisoners; and a bunch of “crime prevention” social service programs, few of them with any demonstrated crime prevention value.

Kleiman also addresses the worst bit of the 1994 crime law, the really nasty provisions that have come to dominate the current, distorted debate over the law:

The one disastrously bad provision of the law was grants to states to build new prisons. Not only was that a bad idea on its own, but it was made much worse by the addition of another conservative shibboleth, “truth in sentencing.” Truth in sentencing is an excellent example of giving a vicious twist to an otherwise sensible idea. Under the old system of “indeterminate sentencing,” there was only a fuzzy relationship between the sentence pronounced from the bench and the time actually served by the offender. … So there was a reasonable case for bringing the actual sentence in line with the nominal sentence, even aside from well-justified concerns that the parole system, which operated largely without published standards, might introduce another source of racial bias.

However, there were two ways to achieve truth in sentencing: shortening the sentence pronounced from the bench (but making the offender serve all of it), thus eliminating the falsehood without changing the time to be served, or eliminating discretionary release while leaving the nominal sentences unchanged, thus in effect tripling effective sentence lengths. The Republicans, who had made prison-building and truth in sentencing the price of their acquiescence with the rest of the bill, insisted that in order to get federal prison-building money the states introduce this concept for violent crimes without shortening nominal sentences.

… It’s simply not the case that the 1994 crime bill created the mass-incarceration problem; most of the damage had already been done. (In 1994, the prison-plus-jail headcount had reached 1.5 million, about triple its 1975 level, on its way to the current peak of 2.3 million.) But the crime bill certainly made the problem worse, and it contributed — directly through the money, indirectly through the rules, and even more indirectly by spreading truth in sentencing as a policy meme — to the policy of continuing to increase the size of the prison population as the crime rate collapsed.

But here’s the important bit about that, for anyone who wants to understand this law rather than just use it to score purity points:

The prison-building money, and especially the truth in sentencing provision, were predictably bad policies, and the people who fought for those provisions should be held accountable for what was at best a bad mistake and at worst an act of pointless, politically-motivated cruelty.

But the people who fought for those provisions almost all had (R) behind their names. In the politics of the crime bill, the death penalty, the anti-prisoner-education provision, and especially prison-building and truth in sentencing were understood to be the conservative interests, while the VAWA, the assault weapons ban, and the “prevention” agenda were designed to appeal to liberals. (The cops provision was designed to appeal to the broader public, but the political muscle behind it came mostly from the White House and, obviously, local law enforcement.)

… The alternative to the 1994 crime bill was not a bill written by the American Civil Liberties Union … but a truly appalling crime bill the Gingrichized Congress would have passed in 1995.

It’s long past time to account for the policies that contributed to our continuing fetish for incarceration. We really need to discuss the elements of the 1994 crime law that compounded that problem, along with all the other policies that caused it. But we need to address that injustice with an eye toward correcting it, not with the goal of congratulating ourselves with the pleasant fantasy that we would have been perfectly pure if we’d been around back in the 1980s and 1990s.

Both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders deserve credit for going toe-to-toe against the Gingrich Republicans of the early 1990s and managing to get VAWA signed into law. But they weren’t able to win a 100-percent victory against their opponents, and the result of that is we got a crime law that has provided both enormous tangible benefits and enormous tangible harm. It’s not fair to either of them to assign them full blame for the latter while denying them any credit for the former. But that’s not the main problem. The main problem is that doing so avoids taking the responsibility we all now share to act on what we now know.

“Some are guilty, all are responsible,” Rabbi Heschel said. The current progressive purity argument is an effort to deny guilt, and thereby to avoid responsibility. That’s unlovely and unproductive.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* The 1994 crime law makes a lousy pretext for a progressive purity fight. The current Democratic primary involves two candidates who both unambiguously supported the Biden Bill in 1994, so anybody looking for a distinction between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders will need to look elsewhere. Their record here is the same.

** In supporting the bill at the time, I was primarily focused on VAWA, but the argument for “community policing” also seemed promising.

If nothing else, Clinton’s “100,000 cops” seemed like a politically possible jobs bill. I want to bring back the WPA and the Historical Records Survey and the Federal Theatre Project and the Civilian Conservation Corps, but since that ain’t gonna happen any time soon, I’ll go along with almost any other jobs program we can get.

Right now, that means I would happily endorse a federal effort to hire 100,000 new parole officers, or 100,000 new public defenders. But not 100,000 new prison guards. Not even one of those.