“Don’t Just Change Refugee Policy,” Melissa Borja writes, “Change the People in the Pews.” That, Borja says, is the aim of the New Sanctuary Coalition, a New York-based, faith-based group that advocates on behalf of immigrants and refugees.

Borja describes the group and its approach as a “multi-target social movement,” meaning it’s trying to win support from both government officials and from “faith communities” as well. That’s a necessary approach because both “targets” require convincing. Many social movements work this way, engaging groups in power to institute change while at the same time also educating and organizing the grassroots support they need to get those in power to listen.

Borja notes that such a two-pronged, “multi-target” approach is necessary when dealing with advocacy for immigrants and refugees, because such work doesn’t usually come with a pre-existing groundswell of popular support:

A look to the past suggests that targeting both government and religious communities as “sites for change” can be very effective. For example, this strategy has been useful in building support for refugee resettlement, which has always been unpopular throughout U.S. history. Public opinion polls throughout the twentieth century illustrate the deep American opposition to refugees. In January 1939, 30 per cent said that the U.S. should resettle Jewish refugees; 61 per cent said it should not. In May 1975, 36 per cent of Americans said that the U.S. should resettle Vietnamese refugees; 54 per cent said it should not. Finally, in October 2016, 41 per cent of registered American voters said that the U.S. should accept Syrian refugees; 54 per cent said it should not. In all cases, a majority of Americans said that the U.S. should not accept refugees; only about one-third said it should.

This is important context to keep in mind when we’re lamenting white evangelicals’ antipathy to refugees and immigrants: “Refugee resettlement … has always been unpopular” with Americans across the board. This could be presented as a mitigating factor in white evangelicals’ defense: Hey, so what if we don’t like refugees? That only means we’re just like everybody else!

But there are (at least) three problems with this defense:

First, of course, is the fact that refusing to aid people in desperate need is just gross. It doesn’t matter what anyone else is doing or saying about it. That doesn’t change one’s own obligation, duty, responsibility, and opportunity. If you’re holding a life preserver and you refuse to throw it to a nearby drowning child, you’re an immoral, irresponsible, indefensible jerk. It makes no difference how many other bystanders might also have been standing around, also too self-absorbed to do what any decent person was obliged to do.

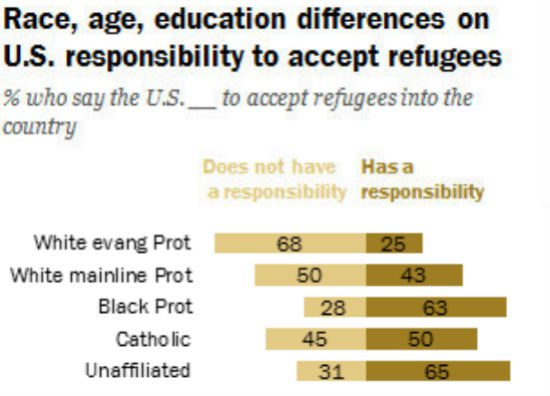

Secondly, when it comes to antipathy, irresponsibility, and generally morally repugnant attitudes toward refugees, white evangelicals are not “just like everybody else.” They’re worse than everybody else.

That suggests that we understated the problem in the previous post. It’s not simply that white evangelicals’ emphasis on “foreign missions” and “Jesus loves the little children” fail to translate into ministry to or love for refugees and immigrants, but that somehow despite — or perhaps in some way because of — all of that, white evangelicals are more likely than anyone else to turn their back on refugees, to turn away the St. Louis, to turn in undocumented residents to the thugs of ICE.

But even if that weren’t the case, even if white evangelicals were far better than they are, which is to say even if they were just exactly like everyone else, there’d still be a huge problem — the third problem with this defense, which is this: evangelical Christians are not supposed to be just exactly like everyone else.

Evangelical Christians claim to follow a distinct sectarian moral code that others, not being a part of that sect, are not bound by. According to their own claims about themselves, they are supposed to be guided in attitude and in deed by the teachings, commandments, and example of Jesus Christ. They are supposed to be bound by the dictates and commandments of the Bible.

There are many, many matters on which the obligations set forth by Jesus and/or the Christian Bible are ambiguous, or flexible, or disputed. This is not one of them.

Yet when it comes to the moral duty to shelter refugees, or to the moral response to the “browning of America,” absolutely nothing about white evangelical attitudes or practice in any way accords with their own purported beliefs. Their actions and attitudes are indefensible on their own terms.

That suggests the wisdom and the necessity of the kind of “multi-target” advocacy Melissa Borja describes:

In current debates about immigration and refugee resettlement, religious leaders from nearly every denomination have opposed the restrictionist and exclusionist policies of the Trump administration. However, lay people have not followed their church leaders on this issue, as evidenced by public opinion polls. A Pew poll in May found that 68 per cent of white evangelical Protestants do not believe that the U.S. has an obligation to accept refugees; only 25 per cent believe that it does. As this and other polls suggest, transforming religious communities remains an important and necessary task for New Sanctuary and other faith-based immigrant justice groups.

Ultimately, the many Christians who are outraged by the plight of separated migrant families need to continue to press the Trump administration to change its policies, and they also need to urge state and local governments to use their powers to hold public and private institutions involved in the current crisis accountable. Government is not the only target, though. Christians also need to work for transformation and conversion in their own faith communities. Government policies need to change, yes, but so, too, do Christian hearts and minds.

But it also suggests that this “transformation and conversion in their own faith communities” she calls for is going to need to be more radical, more fundamental and foundational, than the tacked-on, let’s-also-do-this kind of educational events she reports on:

New Sanctuary leaders unveiled plans for a “weekend of faith” that would use liturgy and congregation-based activities to call attention to the bill and to educate people of faith about current immigration issues, particularly the border policies that have separated parents from their children.

That’s good. That’s nice. That may even be marginally effective.

But it may also be pearls before swine.

Anti-refugee attitudes are not due to a gap in American Christians’ “education” or to some bit of information they’ve unwittingly overlooked. They’re due to a fundamental failure of spiritual formation.

No amount of information or education is going to persuade these anti-refugee folks to follow Christ. They must be born again.