I want to look at three recent, not-quite-connected articles and posts that all seem connected to me. They’re not quite all about the same thing, but I think maybe they’re all around the same thing — like separate orbits circling the same star.

The connecting thread here is the weird contradiction between American white evangelicals’ legacy as the heirs of the great missionary movement and those same white evangelicals’ exceptional antipathy toward immigrants, refugees, and pretty much everyone else who doesn’t look and talk exactly like them.

White evangelicals usually think of themselves as Great Commission Christians, or at least they used to do so. But in 2018, it seems, a defining characteristic of white evangelicalism is fearful contempt toward people in or from “Samaria and the uttermost parts of the earth.”

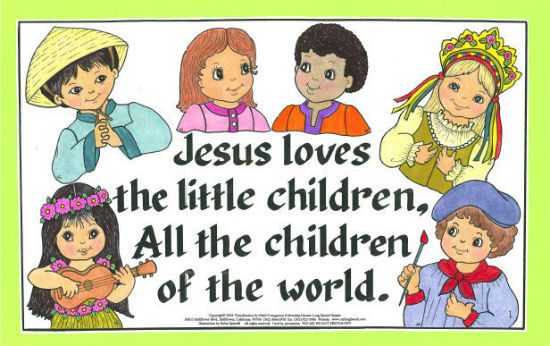

Missionary zeal was a genuine defining characteristic of evangelical Christianity for most of the 19th and 20th centuries. It was an essential component of white evangelicals’ sense of purpose and identity. When I was a kid, you could go to any white evangelical church and start singing “Jeee-sus loves the little chillll-dren …” and everybody’d join in, All the children of the world! Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight. Jesus loves the little children of the world.

And they meant it. They felt it.

Today, though, white evangelicals seem to find their sense of purpose and identity in their politics. And their politics decidedly does not love the little children. It is, rather, the politics that culminated in Shelby County and then led, in more ways than one, to the politics of Donald Trump. Trump ran for office as an explicit white nationalist. The birther-in-chief who still defends the full-page ads he once took out in defense of lynching has only become more baldly and aggressively white nationalist since taking office.

Trump’s narrow election — an electoral win despite an overwhelming loss of the total vote — was made possible primarily due to the enthusiastic support of white evangelicals. As Trump’s self-serving corruption, bigotry, and lethal incompetence has alienated most Americans, his support from white evangelicals has held steady. They love him. They love whatever he loves and they love whatever he tells them to love. They have embraced a Trump-shaped politics and thus a Trump-shaped spirituality. He now defines their religion. He now dictates what it is they believe.

As their support for Trump demonstrates — and as they voluntarily confess in poll after poll — white evangelical religion is today characterized by a contempt for and a fear of all the children of the world. “Red and yellow” and especially black, they are contemptible in their sight.

The immensity of this reversal is astonishing for those of us who grew up in white evangelicalism, who learned and experienced its previous missionary identity firsthand, and who absorbed what then seemed like their once-genuine concern for “foreign missions.”

How is it that the same people who donate special offerings to ministries translating the Bible into every language have come to be the people most likely to whinge that they’re being persecuted by having to “press 1 for English”? (Even though that’s not even a real thing, just a crotchety racist urban legend.) How is it that the same churches that spent the 1990s praying every day for people and nations in the “10-40 Window” are now the people most likely to support travel bans directed at those very same people and nations? How is it that people from churches that march a parade of flags through their sanctuary every year on Missions Sunday are also the same people who choose to pretend to be offended when their neighbors wave those same flags in parades on American streets? And how is it that those same people have chosen to pretend to regard that very word “sanctuary” as a repulsive menace?

Libby Anne of the wonderful blog Love, Joy, Feminism, contemplates this in a recent post: “Why Do So Many White Evangelicals Object to the Browning of America?”

That question arises from a recent survey by PRRI which asked Americans about demographic change: “U.S. Census projections show that by 2043, African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, and other mixed racial and ethnic groups will together be a majority of the population. Do you think the likely impact of this coming demographic change will be mostly positive or mostly negative?”

More than any other group, white evangelicals responded by saying this would be mostly negative:

Among religious groups, white evangelical Protestants are unique in the extent to which they feel demographic change will represent a negative development for the U.S. More than half (52 percent) of white evangelical Protestants say a majority of the U.S. population being nonwhite will be a negative development, while fewer than four in ten white mainline Protestants (39 percent), Catholics (32 percent), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (23 percent) say the same.

Libby Anne — who grew up immersed in white evangelicalism — notes that this exceptional antipathy toward non-white neighbors seems impossible to reconcile with those same white evangelicals’ fervent focus on missionary work:

Evangelicals tend to emphasize missions, and reaching all races with the gospel. Very conservative organizations like prominent creationist group Answers in Genesis argue that all humans are of “one blood,” and that racial distinctions are meaningless. While I was growing up in an evangelical home, my parents hosted international students from the Middle East and Asia, and sponsored children in Africa and South America through World Vision. Mission trips to foreign places are common among evangelicals.

“Where is the disconnect?” Libby Anne asks. “What makes reaching all of the nations of the world with the gospel so imperative, but having those same individuals move to and live in the United States so dangerous?”

I think Libby Anne is correct that there “are multiple answers” to these questions — multiple reasons for this strange disconnect. And I think the main such answer she considers in her post is astute:

A belief that developing populations need white help—and that they are incapable of helping themselves—is in no way incompatible with evangelical missions work. Instead, it’s integral. This creates a broken understanding of the world—an understanding that posits non-white populations as universally and fundamentally less able than white populations, and an understanding that makes it easy to accept the idea that the browning of America is a problem.

That’s a big part of the mix of multiple explanations here. I’ve previously discussed the transformation of evangelical missiology over the past generation, but that change in perspective hasn’t trickled out to the wider white evangelical community, which still views a lot of “mission work” through the same condescending, colonial lens that Libby Anne describes.

But I want to look also at some of the other related factors that made this strange reversal possible — starting with Melissa Borja’s recent essay over on the Anxious Bench, “Don’t Just Change Refugee Policy — Change the People in the Pews.” Borja offers a fascinating look at church-based advocacy for refugees, past and present, and ponders where it will go from here. Let’s all give that a read then come back here soon to continue this discussion.