• “The group turns to prayer, beseeching Jesus to ‘bring forth the skull for the glory of God,’ so that they may shatter ‘the lies of evolution.'”

Roger Sollenberger recounts some of Mark Meadows’ personal history from back before he became Trump’s chief of staff. Back then, Meadows was just a young-Earth creationist, home-schooling white fundamentalist businessman. The group mentioned in the sentence above was a fossil-hunting expedition for fundie home-schoolers on land Meadows would later purchase, then sell (off the books, illegally never reported on his financial disclosures as a member of Congress). It was led by mini-Gothard Doug Phillips, back before he was forced to resign from his Vision Forum for what he called an “affair” and what his 15-year-old victim called abuse.

I grew up among the fundies and knew a lot of Gothard-cult folks at my church and my private fundie school, so I’m sure I could trace some Six Degrees-type connection in that small world between me and Meadows. But Meadows former close relationship with Phillips is a reminder of a different type of “Six Degrees” that I talked about a few years back: “This is a depressing reality for all of us who are — or who ever were — a part of American white evangelicalism. We can all play Six Degrees of Separation From A Rapist. But we never need to use all six degrees.”

• I want to highlight one really sharp insight in Libby Anne’s short rant on White Christian nationalism: “They’re not asking God to help them change hearts and minds so that they can win future elections — no, they’re asking for help overturning one that already happened, based on conspiracy theories and rank nonsense.”

That’s an important distinction. “Changing hearts and minds” — conversion — has long been the foundation of white evangelical theories of politics and social change. On some level, for example, Billy Graham believed that his mass-evangelism was working in parallel with the mass-protests led by his Baptist contemporary Martin Luther King Jr. Billy was confident that if everyone got saved and thereby dealt with the sin in their own lives, society as a whole would be transformed, and that this would actually be a more effective approach than all the unnerving, unsettling things MLK was doing.

That’s an important distinction. “Changing hearts and minds” — conversion — has long been the foundation of white evangelical theories of politics and social change. On some level, for example, Billy Graham believed that his mass-evangelism was working in parallel with the mass-protests led by his Baptist contemporary Martin Luther King Jr. Billy was confident that if everyone got saved and thereby dealt with the sin in their own lives, society as a whole would be transformed, and that this would actually be a more effective approach than all the unnerving, unsettling things MLK was doing.

Graham and the white evangelical world he represented, in other words, believed that personal salvation was the key — that it was both necessary and sufficient as a response to any given social ill or injustice. He believed that no reform was possible without personal salvation, and that personal salvation would, by itself, produce every needed reform. You say you want a revolution? What you really want is a revival.

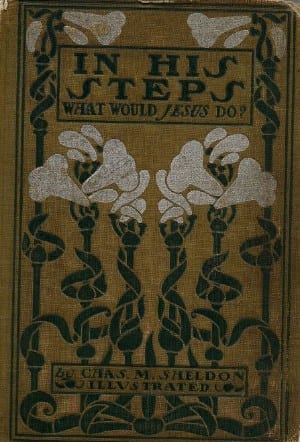

This approach has long, deep roots in white evangelicalism. Consider, for example, Charles Sheldon’s In His Steps — the WWJD? book that became a runaway best-seller a generation before Billy Graham. Sheldon was both an evangelical and a Social Gospel socialist, but he envisioned socialism sweeping the nation as an after-effect of mass conversion and religious revival. This idea of reform-through-revival held sway among white evangelicals throughout most of the 20th century.

I’d point to the examples of the first and second Great Awakenings as evidence that this theory simply doesn’t work. And I’d further suggest that folks like Billy Graham and Charles Sheldon were exceptional in their apparent good-faith belief that it would work, skeptically pointing out that many others likely embraced this theory not because they hoped to bring about reform/revolution through revival, but because they preferred to distract from reform/revolution by shifting the focus to otherworldly revival and opiating the masses. But that’s beside the point here.

The point here is that white evangelicalism in the 21st century appears to have abandoned its former belief (or former pretense) that mass-revival would bring about a better world. Their actions can no longer even semi-plausibly be explained by such a belief. Their actions are no longer consistent with a religion or a political movement that believes what Graham and Sheldon once did. But their actions are entirely consistent with a movement of militant white nationalism driven by a fearful need to maintain and expand white patriarchal hegemony and to put women, religious minorities, and all non-white people back in their place as subordinates.

• It’s still Christmas — even those who don’t follow the liturgical calendar still have their lights up — so here’s a Christmas song (and the source of the title of this post).

I first heard this one in an auditorium/studio at Sony’s New York offices where — thanks to Dwight Ozard and Tom Willett — I had a ticket for the live broadcast of Bruce Cockburn’s Christmas concert back in, like 1992. Cockburn’s guest was Jackson Brown, who got a little off-script in his long introduction to this song. He started off saying that he wasn’t trying to criticize all religion, but then started digging himself into a hole talking about the Satanic Verses and Salman Rushdie and religious leaders who couldn’t tolerate any criticism and just when we were realizing he wasn’t sure where all this was going Bruce Cockburn cut him off and bailed him out by saying, “Well, you know, f–k ’em if they can’t take a joke.” This was, again, a live radio broadcast, and it was quite fun to watch the engineers scramble to bleep expletives during what was supposed to be a wholesome Christmas concert.

Anyway, here’s “The Rebel Jesus“: