Last week we briefly discussed an interview with Christian rapper Lecrae by the Atlantic’s Emma Green, “The Political Gains and Lost Faith of Evangelical Identity.”

This is Lecrae’s personal testimony. It’s the tale of a crisis of faith brought on by fellow believers, by “brothers and sisters in Christ” whose lack of love and refusal to love forced Lecrae to recognize the truth of what 1 John 4 tells us:

Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love. … Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.

The personal story Lecrae tells closely parallels the one told by Jemar Tisby on the “Pass the Mic” podcast, “Leave LOUD: Jemar Tisby’s Story.” (We discussed that here a few months back, see: “A cow eating grass.”)

Tisby, like Lecrae, was once a rising star in the same Very Reformed branch of white evangelicalism, the stream associated with the Gospel Coalition and John Piper and that crowd. Tisby got his MDiv from Reformed Theological Seminary and he founded and led a group called RAAN, the Reformed African-American Network.

Tisby loudly left that white Reformed world after it turned on him, shut him up and shut him down the same way it turned on Lecrae — and for the same reasons (the piously “a-political” politics of whiteness). I described his “Leave LOUD” testimony here this way:

It is, in part, the story of the subtle ways that whiteness works to exclude non-whiteness, the ways that whiteness gets enshrined into doctrines allowing the enforcement of whiteness to be exercised as a “spiritual” discipline of maintaining doctrinal orthodoxy.

But it’s also in part a not-at-all subtle story of explicit white power and unadulterated white-nationalist, Neo-Confederate racism indistinguishable from any of those 19th-century arguments among white groups of white Christians. Which is to say, it’s in part the story of how a movement that makes space for Doug Wilson cannot also be a movement that makes space for Jemar Tisby. Give it a listen. (It’s compelling, lively, sometimes heart-breaking/enraging and sometimes funny — and unlike many podcasts, it doesn’t include any awkward segues into trying to sell you a new mattress or to use Stamps.com.)

For both of these devoutly Reformed men, the cracks in their relationship with their white Reformed community began in 2012 when their grief over the murder of Trayvon Martin was met with a dismissive, prickly defensiveness. That defensive denialism from their white Reformed brethren intensified after the Ferguson protests and the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Both men testify to the way that the bland affirmation of “racial reconciliation” in that community bristled into something more hostile whenever the discussion turned to any manifestation of racism that went beyond individual, personal, emotional animus. The community wasn’t willing to listen when it came to the reality of systemic or institutional racism.

The irony here is that, again, this all happened (and is happening) in Very Reformed circles, and one would think that Calvinists are — or ought to be — well-equipped to appreciate and understand the reality of systemic injustice pervading institutions, culture, religion, law, and politics. America’s long history of intrinsic, systemic racism is exactly the sort of thing that Calvinists ought to expect. It’s a demonstration and a confirmation of everything they believe and teach about human nature.

I am not a Calvinist, but my disagreement with Very Reformed theology isn’t based on its rather noirish view of human nature. I think they get that mostly right. I disagree, rather, with their rather pessimistic view of the nature and character of God.

I suppose one way to put it would be that I think Calvinists are excellent at conveying the enormity of humanity’s need for divine grace but very bad at appreciating the enormity of that divine grace — which they see as parsimonious, capricious, and ultimately insufficient. (No, that’s not a charitable description — they’d never use or agree to such terms, but they’ve never convinced me why or how they’re inaccurate.) So in a sense, I affirm the Calvinist view of human nature but not the Calvinist view of God’s character (hence my fondness for Niebuhr).

The Reformed/Calvinist view of human nature cannot predict precisely what form sin, evil, and injustice will take in any given society or historical context, but it does tell us to expect that sin, evil, and injustice will always be present. It tells us to expect that these will be pervasively present in every aspect of every human endeavor. Systemic sin and institutional sin should never be surprising or confusing or confounding for Christians from this tradition.

White Calvinists, in other words, shouldn’t be threatened by discussions of systemic racism in America or in Christendom more broadly. They should recognize what they’re hearing and say, “Ah, alas, there it is” because this is exactly the sort of thing their theology has taught them to expect to find everywhere and anywhere.

There’s a terrific, fiercely Calvinist rant somewhere in Jonathan Edwards (I can’t find it just now) where he discusses the pervasive, inescapable rot of human sinfulness. He’s writing against some other theologian who apparently had suggested that human “depravity” was located in a single aspect of our nature — in our “will,” perhaps, or in our “conscience.” So Edwards methodically ticks through a list of such potential candidates for the location of our sinfulness — the will, the conscience, the intellect, the body, reason, emotion, etc. — arguing, like a good Calvinist, that every such aspect of our humanity is both infused with the image of God (and therefore good) and tainted by our fallen sinfulness (and therefore unreliable, imperfect, and incapable of saving us).

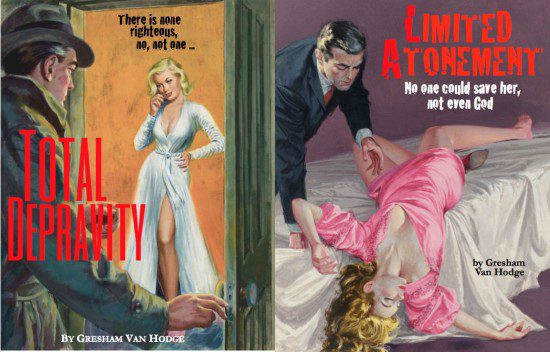

This is what Calvinists mean by “total depravity” — which, again, does not mean utter depravity or superlative depravity, but something more like pervasive depravity. Sin, Reformed theology teaches, taints everything.

And for good Reformed theologians, this doesn’t only apply to us as individuals, it’s also true for institutions, laws, cultures, traditions, families, guilds, congregations, churches, nations. The systemic embodiment of our pervasive human sinfulness, they believe, ensures that no human institution can ever be untainted by sin, injustice, and evil.

All of which makes the testimonies of Lecrae and Tisby even more depressing and disappointing. If they had instead been a part of, say, some Holiness tradition of white evangelicalism — one that held out the possibility and promise of perfect sanctification — then their white brethren’s confused hostility to the reality of systemic injustice might be more understandable. If they’d come out of the hyper-individualist sign-your-Billy-Graham-crusade-decision-card strain of white evangelicalism (a theology designed to avoid acknowledging or addressing systemic injustice), then this hostility and confusion would be expected.

But these were Very Reformed Calvinists. They ought to have known better. (Or, if you will, they ought to have known that they couldn’t know better.) When you see Calvinists defensively denying the possibility of pervasive sin and proclaiming their own untainted innocence then you really begin to appreciate how whiteness and white supremacy have twisted white Christianity in America.