(Second verse, same as the first …)

One of my favorite things about “Highway Patrolman” is the realism of one imaginary detail. Joe Roberts’ happiest memory of his brother involves nights out at their favorite bar:

Me and Frankie laughing and drinking

Nothing feels better than blood on blood

Taking turns dancing with Maria

As the band played “Night of the Johnstown Flood”

The reference there is to a famous song about a famous tragedy. Joe assumes that you know this song because, after all, who doesn’t? Except there is no such song.

That seems impossible. If you didn’t already know that there was no such song, you’d be certain that “Night of the Johnstown Flood” was surely one of the songs in that list of essential American music that Johnny Cash wrote for his daughter. You might even be half-certain that you’d heard Johnny’s own recording of it. Or maybe it was Patsy Cline’s. Or Pete Seeger’s. Or Mississippi John Hurt’s.

The granular details of Joe Roberts’ rank and assignment — “I’m a sergeant out of Perrineville Barracks Number 8” — help to ground Springsteen’s story in reality even though the song’s geography doesn’t correspond to any actual map. (Perrineville is in Jersey, not Ohio or Michigan, and there’s no such place as “Michigan County” either.) But the fictional invention of those details doesn’t bother or baffle me. The non-existence of the song “Night of the Johnstown Flood” does.

In 1889, the South Fork Dam collapsed 14 miles upstream from the city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, unleashing a furious wall of water that swept through the city, killing more than 2,200 people. That’s just the sort of tragedy that one would expect would be memorialized in the kind of popular song that would become a standard for generations. The fact that victims and survivors of the flood were repeatedly denied compensation by the corrupt corporate-controlled courts of the Gilded Age makes that tragedy even more of a perfect candidate for a song like “Night of the Johnstown Flood” to emerge as the kind of Americana music small-town bands would still be playing 80 years later.

And yet the song did not exist. I suppose this was partly just bad timing. In 1889, Stephen Foster was already dead and Woody Guthrie hadn’t yet been born. Joe Hill was only 10 years old and Lead Belly was just an infant. But that other great American composer, “Anonymous,” was around then, and it seems wrong, somehow, that such a reliably prolific songwriter never bothered to give us the actual “Night of the Johnstown Flood.”

It was only the dream-within-a-dream of a song-within-a-song — like the Monster Mash, or the beautiful Tennessee Waltz, or the Best Song in the World to which Tenacious D paid Tribute. I say “was” because several musicians have subsequently written songs titled “Night of the Johnstown Flood,” but these were all composed after Nebraska and because of it.*

The Johnstown Flood used to always appear in those horrifying lists of American tragedies. Those lists were popular back in the early 2000s as Americans struggled to cope with the aftermath of the nearly 3,000 killed on a single day in the 9/11 attacks. The grim toll of the flood was listed alongside other calamities like the Galveston Hurricane and the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and the Great Chicago Fire.

I never noticed at the time that the “Spanish” [Kansas] Flu pandemic wasn’t included on those lists. The 1918 wave of that pandemic killed some 675,000 Americans, rivaling the whole of the Civil War, but somehow not getting counted in our recounting of national tragedies.

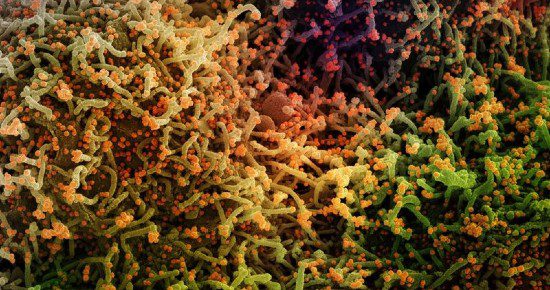

The current pandemic has already surpassed that death toll. It has also altered the way we understand and respond to past events like the Johnstown Flood. We read “2,209 Americans died” or “2.977 people died in America” and we’re not sure if it’s a historical account of some great national tragedy or just a statistic from an average Wednesday.

I suppose this is partly due to the overwhelming scope and scale of this ongoing national and global catastrophe. The Johnstown Flood was horrible, but it ended, and so the nation was able to react and to respond, sending rescue workers and sending money to Clara Barton in a vast outpouring of mutual aid. This isn’t ending, and so we’re not sure what to do or how to do it. Cheering and banging pots for hospital workers seemed appropriate, initially, but that whimpered out as it sunk in that it didn’t seem any more tangibly constructive than “thoughts and prayers.”

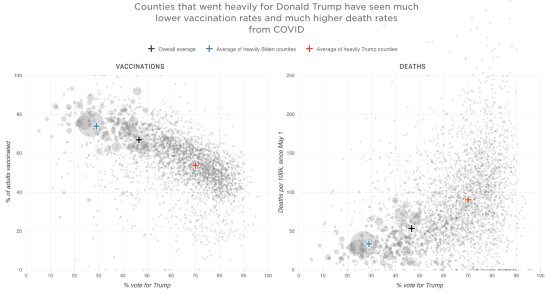

But I also worry that our wholly disproportionate lack of response to this tragedy — as compared to things like the Johnstown Flood or the San Francisco Earthquake, and as compared to the scope of the thing itself — is not because we’re overwhelmed but because we’re underwhelmed. We don’t seem to care as much as we should or as much as we need to.

The “we” there is, admittedly, fuzzy. I don’t mean any one person specifically — not you, or me, or any of the beleaguered public health officials struggling to save lives even as others pressure them not to “over-react” or to “move forward” and “get back to normal.”

What I mean with that clumsy “we,” I suppose, is something that Sarah Smith wrote about in a piece I linked to earlier this week. The bit I quoted then haunts me:

On a societal scale, one of the fastest ways for two deeply entrenched, opposing groups to start seeing each other as fellow humans again is to give them something bigger to fight against together. It’s an “Independence Day” sort of scenario, Chester, the Virginia Commonwealth University professor, said: If aliens invaded, countries who hate each other in normal times would suddenly work together against an external threat.

But the external threat with the potential to unite a deeply polarized country, he said, should have been the pandemic. And it didn’t happen.

The original Night of the Living Dead creeped me out. The zombies were scary and, to this day, if I’m walking in the dark and someone starts saying “They’re coming to get you, Barbara!” I will remember those zombies and the fear of them. But the more deeply frightening and unsettling thing about that movie — filmed just a short drive from Johnstown — was not its gory monsters, it was the way the protagonists failed to come together against them. Spoiler alert: They all die. Thematic spoiler alert: They might not have if they hadn’t all turned against each other.

Then again, just as there was no such song as “Night of the Johnstown Flood,” there is little enduring cultural memory of the “Spanish” flu pandemic and its staggering death toll. I’ve seen more discussion of that pandemic from a century ago in the past two years than I ever did in my previous half-century of life. It was a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it, forgettable footnote in all of the history classes I took in high school and college, and it hasn’t lived on in songs or stories the way that localized tragedies often do. The National Park Service runs the Johnstown Flood National Memorial, but the closest thing to a national memorial for the Spanish flu pandemic is a granite bench in a Barre, Vermont, cemetery, put up by a local restauranteur to mark the centennial of his grandfather’s death.

Why is that? Is it because, again, the scope and scale of a pandemic is just more than we can manage to comprehend? If so, then is our inability to respond proportionately contributing to the deadly effects of the pandemic? Does the seeming unreality of the vastness of the thing contribute to the relative unreality of our response?

Whatever the cause, we seem to be retreating or retrenching from the solidarity that ought to be strengthened by “the external threat with the potential to unite.” Maybe this is partly because of the nature of a pandemic, which makes social distancing and isolation an obligation of love for neighbor. But in any case, “we” aren’t acting as though the deaths of others are the deaths of family. And “we” aren’t acting as though the lives of the millions still at risk are the lives of family.

And, as the man sang, if we turn our backs on family, we just ain’t no good.

* Here are various attempts to complete the assignment from the Rock Creek Jug Band, Nolan Patton, Chicken Little, and the Delta Generators. My favorite there is probably the Chicken Little song, although it has a 21st-century sensibility in its approach to the 19th-century catastrophe. The Rock Creek Jug Band understood that this needed to be a song one could dance to, and I’d love to hear a good bar band’s rock arrangement of their version. Patton’s song is pretty, but he seems to have written a sequel to “Highway Patrolman,” not a version of the older song. The Delta Generators’ blues take isn’t quite right for dancing with your sister-in-law, but it does a great job of getting at the Cain and Abel theme underlying both Springsteen’s song and the man-made catastrophe it references.