You may have seen the viral video that prompted this article from the Houston Chronicle, “Viral Texas knife shop owner talks about rejecting ‘Nazi bulls–t’.”

Johnathan Sibley, an East Texas bladesmith and co-owner of The Blade Bar in Edom, was simply doing his job when a man and woman asked him to work on two knives. But the 20-second interaction between Sibley and the couple, captured on video, has quickly made Sibley a viral sensation.

“What are we wanting to put on them?” asks Sibley after being shown the knives. The woman tells Sibley that they’re Hitler Youth knives, and she wanted Sibley to transfer the diamond emblem on one knife to the second, which had a visible engraving.

“No, I won’t do it,” Sibley says, pushing the knives back to the woman, who asks why. “No Nazi bulls–t.” The woman pauses for a moment, then accepts Sibley’s answer. He then says that he would put a modern German forestry seal on the knife. “I will denazify s–t, but I won’t re-nazify s–t.” The woman says “No problem,” and she and the man walk out.

Apart from the cussing, Sibley is remarkably polite and even, in a way, kind to the couple. He explains what he can and cannot do for them and offers them a face-saving invitation to do better, but does so without any moralistic condescension. He’s demonstrating moral clarity, but not imagining that this affords him moral superiority.

Because, after all, “No Nazi bulls–t” is such an absolutely minimal moral standard that nobody deserves to congratulate themselves for clearing that bar. That’s what Sibley thinks, anyway, which is why he seems genuinely disappointed at the praise he’s gotten for what he correctly thinks ought to be an unremarkable act:

“It shouldn’t be worthy of the attention it’s getting. It should be standard practice,” Sibley said. “I thought we had an agreement on this s–t 80 years ago.”

We did. But part of the reason we came to an agreement on this 80 years ago is that we were unable to come to that agreement 90 years ago. At that point, “Nazi bulls–t” hadn’t yet been fully exposed for what it was or for what it required or for where it led. We reached “an agreement on this s–t” only after the horror of its consequences were fully revealed.

We learned from that. We learned the hard way, but lessons learned the hard way are too hard-earned to be easily forgotten. Or, at least, they should be.

Masha Gessen puts it this way:

We are not any smarter, kinder, wiser, or more moral than people who lived ninety years ago. We are just as likely to needlessly give up our political power and to remain willfully ignorant of darkness as it’s dawning. But we know something they didn’t know: we know that the Holocaust is possible.

Again, this knowledge doesn’t make us better than “people who lived 90 years ago,” but it does give us an advantage they did not have. And it gives us an obligation to make the most of that advantage — to act on it as “standard practice.”

That advantage can help us to succeed where they failed. It gives us the opportunity to prevent that which is possible from happening again.

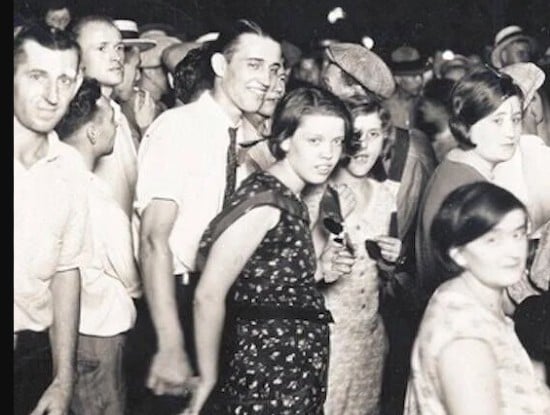

And sure, yeah, if we succeed at that, I suppose you could argue that does make us “better than” those people or “more moral” than they were. But, again, you don’t win any prizes for that or earn any congratulations for being “better than” mass-murdering racist Nazi bulls–t — for being “better than” the people in the photo above. That’s the absolute bare minimum. Anybody seeking praise for that has lost the plot in a dangerously delusional way.

Dangerous because, as I’ve written here before, “The surest way to become a monster is to imagine you’re a hero.” Or, in terms of 90 years ago: “The surest way to become Martin Niemöller is to convince yourself that you’re already Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The only way to become Bonhoeffer is to recognize that you’re far more like Niemöller than you want to admit.”

This is why the humility expressed by both Sibley and Gessen is part of the “agreement” — part of the lesson that, if learned, enables us “know something they didn’t know.” It’s the humility that allows us to learn prevent the killing of the prophets instead of standing around congratulating ourselves by fantasizing about how “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.”

That’s Matthew 23:30 — part of a passage in which Jesus notes that it’s just exactly the sort of people who go around saying “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would have done everything right and nothing wrong” who are, right now, at this very moment, killing and persecuting the prophets, just exactly as their ancestors did. Pride tempts us to chase after “better than” and thus to fail at “good.” Or even to fail at “absolute bare minimum.” This is the end result of Satanic baby-killerism in all its forms — becoming so obsessed with “being better than” that you’re unconcerned with and incapable of doing good, choosing good, or acting good. (No, I don’t mean “well.”)

But this humility does not entail ambiguity. It does not allow for ambiguity.

“Shedding the blood of the prophets” is Bad. It’s Evil. Our ancestors ought to have known that. We ought to know it. We have less excuse not to because we have the advantage of knowing something our ancestors didn’t know and of learning from their morally disastrous example. Humility allows us to learn from them, and what we learn from them is clarity. Humility allows and requires us to say “No Nazi bulls–t” without hesitation or qualification.

It’s also what allows us to say, following Gessen: We are not any smarter, kinder, wiser, or more moral than people who lived 130 years ago. But we know something they didn’t know: we know that Jim Crow segregation is possible.

This knowledge, Gessen argues, entails an obligation: “To prevent what we know can happen from happening” again.

That obligation means saying, like Sibley, “No, I won’t do it.”

Because we had an agreement on this s–t 80 years ago. And because we had an agreement on this s–t 60 years ago.