Lately I’ve been reading about “design thinking,” and I’m starting to see its potential as a tool for community renewal.

Design thinking is a structured approach many designers use to generate and develop ideas, products, and innovations. It’s most often associated with IDEO, the well-known design firm that created the first Apple mouse, and Stanford’s Institute of Design (a.k.a. “d.school”). But what began as a process to guide the development of new consumer products is now being applied, often by non-designers, to business (including Apple, Target, and Proctor & Gamble, as well as social entrepreneurs like the d.light company recently highlighted in “This Is Our City”), nonprofits, health care, government, and K-12 education. The visionary designer Bruce Mau is using design thinking to help a community group in Sudbury, Ontario, a city blighted by decades of nickel mining, to uncover hidden assets and reimagine itself for the 21st century.

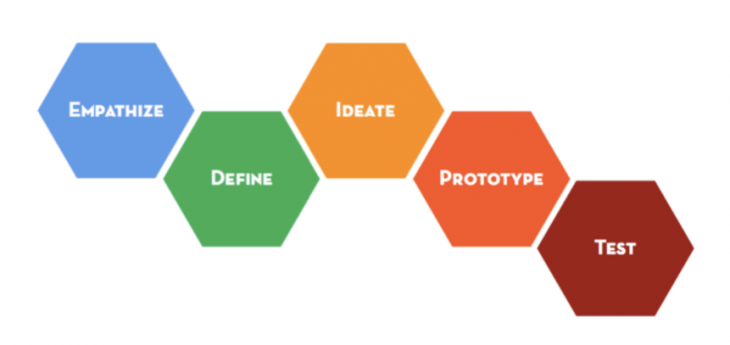

The stages of design thinking are sometimes laid out like this: Empathize (or observe), Define (or interpret), Ideate (or brainstorm), Prototype (or experiment), and Test (then improve).

One of the reasons I’m attracted to this subject is that it seems to take seriously Einstein’s warning that we can’t solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them. The reason I think it might be relevant to our work in our neighborhoods is that it is empathic and human-centered, action-driven, multi-disciplinary, collaborative, and conversational. It takes physical space seriously. It also strikes me as a powerful complement to community strategies like asset-mapping and appreciative inquiry. Our friends at the Parish Collective talk about faith communities “weaving a fabric of care” in their neighborhoods. Here, too, is something I appreciate about design thinking: its emphasis on serendipitous connection-making. Warren Berger writes in Glimmer, his book on design thinking:

The best designers seem to have a natural eye for spotting patterns and discerning possible relationships between things that most of us view as being separate and unrelated. Once they see a possible relationship, they work to make the pieces fit.

When we gather as parish practitioners, I can see design thinking being a useful tool to collaboratively address the needs and opportunities of our particular places. It’s also a lot of fun.

This fall I want to do an experiment. I have a theory that design thinking is one way collaborators of all stripes can work together to address some of the persistent challenges faced by rural communities like the one I live in. To test my theory I want to invite a diverse group of friends to my house for pizza cart pizza, beer and soda, and a design thinking crash course. I’m hoping we can identify a need or opportunity in Silverton, and—far more quickly than is ideal—capture our observations and analysis, brainstorm ideas, and then prototype our proposed response.

Design thinking is controversial even among designers, not least because it focuses on a process rather than on innate creative intelligence, and because it is being “given away” by prominent designers to non-designers. But my hunch is that design thinking holds a lot of promise for Slow Church and the parish movement.

If you’re in the Silverton-Mt. Angel area and you’re interested in experimenting with me, let me know. And if you’re interested in reading more about design thinking, here are some resources I’ve found helpful so far:

Books:

- The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm, by Tom Kelley

- Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation, by Tim Brown

- Glimmer: How Design Can Transform Your Life, and Maybe Even the World, by Warren Berger

- Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Community Collaboration, by Scott Doorley and Scott Witthoft

Around the Web:

Stanford d.school

Design Thinking for Educators

IDEO.com

IDEO.org

Tim Brown (CEO of IDEO)