Why is forming habits important? My claim is this: habits have to do with your salvation. Before you decide I’m a Pelagian, allow me to explain.

Virtue vs. habit

Throughout this series, I’ve been vacillating between talk of habits and talk of virtue. Typically, the “habits” we think of are waking up on time, brushing our teeth, and hitting the gym. Aren’t habits and virtue two separate things?

Not according to the Catechism:

A virtue is a habitual and firm disposition to do the good. It allows the person not only to perform good acts, but to give the best of himself. The virtuous person tends toward the good with all his sensory and spiritual powers; he pursues the good and chooses it in concrete actions. (CCC 1803)

Put more simply, in the words of St. Augustine, “Virtue is a good habit consonant with our nature.”

A broader notion of habit

To accept that virtue is a habit, we have to broaden our understanding of habit. A habit isn’t just your daily schedule, but an ability or a power that you acquire through repetitive action.

Some (looking at you, Kant) believe these powers are independent of the mind. In other words, habitual actions are mechanical or automatic.

In some senses, Kant is right: habitual actions are facilitated by changes in your character. However, these changes that occur through what you repeatedly do, and there still remains a voluntary element of habitual acts. So habits aren’t independent of the mind.

With this definition of habit, we don’t just have to think about your daily schedule. You can have a habit of health, a habit of gratitude, or a habit of courage. A habit of choosing the good is virtue.

Foundations of virtue theory

The understanding of virtue as a habit is a tradition that goes back millennia. Aristotle was the first theorist of virtue ethics or arete — “excellence.” For Aristotle, possessing the moral virtues or moral excellences is the way that the human person flourishes. In other words, the virtues are the foundation of “the good life.”

Aristotle understood the virtues as capacities, or attitudes of the human persons. This has two implications.

First, virtue must be intentionally sustained and developed. Virtue is not a one-time decision, but a habit, and must grow over time through consistent work. Second, virtue is not something outside the human person. It’s not like an interest, an extracurricular activity, or even a skill. If it’s a habit, it lies at the foundation of our very being.

The four cardinal virtues, identified by Aristotle but systematized by Plato, were Prudence, Temperance, Courage, and Justice.

- Prudence, also known as practical wisdom, is the most important of the four. It is the ability to discern to right course of action to take in any given moment.

- Temperance, also called self-control, means your ability to moderate your desires.

- Courage is not just strength. It’s the ability to choose the right thing in the face of fear, uncertainty, or intimidation.

- Justice is also fairness. This means you are able to recognize what’s good for the community and act according to that good.

Aristotle believed that, in order to grow in these four virtues, you must first imitate another who exemplifies such virtuous characteristics. By practicing the habits of this person, you can make them your own customs. Eventually, you will unite the four of them in a virtuous disposition. Virtue will constitute your character, and you will lead an excellent life.

A step further: St. Thomas Aquinas

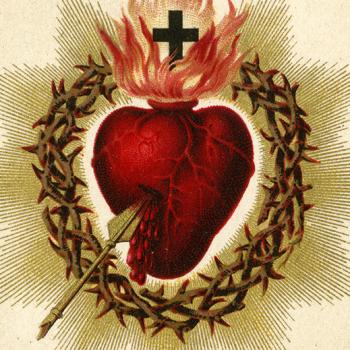

Aquinas, centuries after Aristotle, took up Aristotelian ethics and used it as the basis for his exposition of Christian virtue. But in his Treatise on the Virtues, Aquinas goes a step further than Aristotle. The highest virtues, in Aquinas’ view, are the theological virtues of faith, hope and love.

Although they are habits of the human person, just like any other virtue, Aquinas believes the theological virtues must be infused, given to us by God’s grace.

We are finite and flawed human beings, and we can never make ourselves perfect. But God doesn’t wait off in the distance as we struggle with our fallen state. God Himself reaches down and infuses virtue in us. God bent down in the Incarnation and took on our human nature, freely communicating to us a grace that is not of this world.

Our need for grace

This is hugely important to remember throughout our pursuit of virtuous habits. When we fail in our pursuit of the good — in relationships, in our faith, in our free time — we must remember that we are not meant to be self sufficient.

Our need for grace doesn’t excuse us from working toward virtue, because grace requires active participation of the individual to bear fruit. In the language of neuroscience, we might say that re-wiring brain circuits is the mechanism through which our nature cooperates with God’s grace.

But ultimately, we did not create ourselves and will not save ourselves. We were made to rely on His grace, and so we can begin again.

Find the rest of this series here.

Further reading recommendations

For virtue ethics, read Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, or Aquinas’ Summa, 1.11 49.1-4, 55.1-2.

For a great philosophical exploration of the connection between habits and the virtues, read Prof. Stanley Hauerwas’ lecture “Habit Matters: The Bodily Character of the Virtues,” given in 2012 at the The Von Hügel Institute.