In this season, many of us are likely practicing some form of asceticism. The word ascetic comes from the Greek “askein,” which is translated as “to exercise.” Thus, its origin captures its true meaning: training in self-discipline.

In our modern life, we have an aversion to such practices. But this attitude is grounded in a misunderstanding. We see asceticism as nothing more than penance, equating self-denial with self-punishment. But this is a misinterpretation. Ascetic discipline is not just to atone for our faults, but build up our virtues. Furthermore, we may see ascetic practices as dualistic. But in reality, they do not seek to eliminate our corporeality, or create distance between ourselves and our embodied experience. Rather, asceticism aims to liberate us from the fallen aspects of our nature. To free us from attachments to material comfort, to our personal preference, to our immediate reactions. In doing so, asceticism allows us to adhere to our deeper desires. And so, it makes us more fully human.

When asceticism goes wrong

One of the reasons we are wary of asceticism is because it can go wrong. Sometimes, practices can become so extreme that it interferes with your life. For instance, if I’m eating nothing but bread and water all the time, this can impair my daily functioning, reduce my presence of mind, and inhibit my capacity to share life with those I love. In these cases, the practices are not likely to build me up in virtue.

Other times, pride gets involved. We may begin to adhere to our practices for the practices themselves, rather than for the detachment that is their aim. In this case, our intention is perfection, not liberation. Our intention is to follow the letter of the law, rather than the spirit. Thus, the ascetic practice is ultimately making us more attached – to our own will.

Finally, we should balance our fasting with feasting. Times of asceticism should be followed by times of celebration and abundance. This cycle fosters gratitude, and an awareness of God’s merciful love. And without it, asceticism can easily dry up into a moralistic project of self-perfection.

An image for asceticism

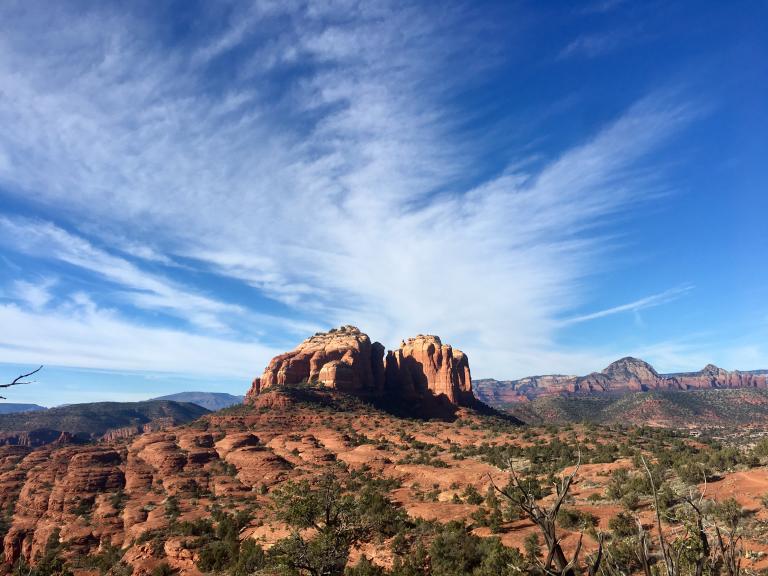

As we strive to properly understand and embrace asceticism, it can be helpful to use the image of a desert. The desert, in Scripture, is the setting of ascetic experiences. Throughout the Old Testament, it a place of wandering and conversion for the Israelite people and their prophets. Not only John the Baptist, but Christ Himself enters the Judean desert. For forty days, he fasted and prayed as he engaged in a spiritual struggle against temptation. This association between desert landscapes and asceticism has continued to unfold in the history of Christianity through the lives of desert monks.

A few months ago, I had the privilege of spending a week hiking in Arizona near Sedona. I was blown away by miles of layered rock, an alternating pattern of deep red and brown that stood in stark contrast to the piercing blue sky.

These distinctive landforms formed over the course of millennia. Some were shaped by rivers and streams that flowed over the land, cutting through soft rock formations of sandstone and limestone to form canyons and crevices. Others, by the retreat of oceans. From one day to the next, the landscape looked the same. But over time, the older layers of earth emerged.

Authentic asceticism operates in the same way. Rather than extreme self-mortification, ascetic practices are usually quite ordinary. However, they have the power to gradually strip us of our “softer” and weaker characteristics. To receive this transformation, we must be patient and consistent. But it’s worth it, asceticism has the quiet power to reveal our authentic selves.

Have the courage to enter the desert of your life.