Over the years, Franklin had been developing a social outlook that, in its mixture of liberal, populist and conservative ideas, would become one archetype of American middle-class philosophy. He exalted hard work, individual enterprise, frugality and self-reliance. On the other hand, he also pushed for civic cooperation, social compassion, and voluntary community improvement schemes. He was equally distrustful of the elite and the rabble, of ceding power to the well-born establishment or to an unruly mob. With his shopkeepers values, he cringed at class warfare. Bred into his bones was a belief in social mobility and the bootstrap values of rising through hard work.

…

[Welfare] laws were compassionate. But he warned that they could have unintended consequences and promote laziness. . . Not only did [Franklin] warn against welfare dependency, but he offered his own version of the trickle-down theory of economics. The more money made by the rich and by all of society, the more money that would make its way down to the poor. “The rich do not work for one another. . . Everything that they or their families use and consume is the produce of the laboring poor.” The rich spend their money in ways that enrich the laboring poor: clothing and furniture and dwellings. “Our laboring poor receive annually the whole of the clear revenues of the nation.” He also debunked the idea of imposing a higher minimum wage: “A law might be made to raise their wages; but if our manufactures are too dear, they might not vend abroad.”

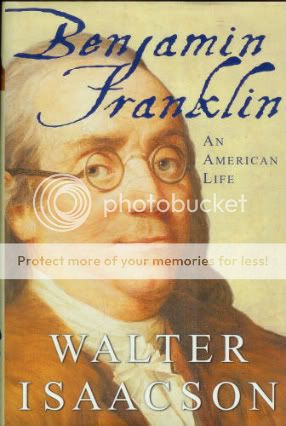

– Chapter Eleven, Walter Isaacson’s Benjamin Franklin, An American Life

If you found yourself reading the above and identifying with that description, or even punching the air with a “boorah, damn straight, ” you will probably like this book, very much.

I picked it up back when it came out, a few years ago, and stuck it into my “will-get-to” pile. This summer, recalling how much I enjoyed finally getting to McCullough’s John Adams last summer, I dug into it, and I regret waiting so long to read this excellent book about a man who could rightly be called the First American; certainly Franklin was the embodiment of the energetic, pragmatic, optimistic and upwardly-mobile middle class that has come to personify America in millions of minds. Franklin might be called the model from which the “can-do spirit” of America was struck.

As with the Adams books (and lately so many books I really like) I have been foregoing my usual neurosis about needing my books to look “pristine and unread” and have been dog-earring pages and writing in the margins, so I could share excerpts with you guys (you see what I sacrifice for you?), but before I get to them, let me just say that Walter Isaacson’s Benjamin Franklin, An American Life is no pedantic tome. Isaacson clearly admires his subject and understands him very well, and so he writes affectionately, his clear prose as inviting as a gossipy letter sent by a friend who has a way with words. And he has a little fun at the expense of his own comrades, from time to time:

What would have happened if Franklin had, in fact, received a formal education and gone to Harvard? Some historians. . . argue that he would have been stripped of his “spontaneity,” “intuitive” literary style, “zest,” “freshness,” and the “unclutteredness” of hsi mind. And indeed, Harvard has been known to do that and worse to some of its charges.

As Isaacson is a deeply-in member of the Mainstream Media (CNN, Time Magazine) he later adds:

Fortunately, Franklin acquired something that was perhaps just as enlightening as a Harvard Education; the training and experiences of a publisher, printer and newspaperman.

Isaacson’s affection for Franklin, though, does not inhibit his portrait of this largely self-educated and brilliant man who let nothing, not even his lack of an “elite” education stop him from pursuing his interests. Franklin’s relentless curiosity and propensity for finding unique solutions to rather new problems are delightful to read, but the sly manipulations and the weird dualities of his private life are amply covered, too. When Franklin has behaved like a bastard, the reader understands that he’s been a bastard, but these faults merely remind that for all his fantastic gifts, Franklin was a human and quite imperfect. It is with a knowing (and forgiving) sigh that we continue our eager read; watching Franklin evolve – and he does, continually, on public matters if not so much in his private life – is very encouraging for the rest of us!

To the promised excerpts:

“I am . . . a mortal enemy to arbitrary government and unlimited power. I am naturally very jealous for the rights and liberties of my country; and the least appearance of an encroachment on those invaluable privileges is apt to make my blood boil exceedingly.”

– Franklin, writing as “Silence DoGood”

“Without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom. . . and no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech.”

– Franklin, writing as “Mrs. DoGood”

“So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.”

– Franklin, on rationalizations

Nevertheless, he soon came to the conclusion that a simple and complacent deism had its own set of drawbacks. He had converted [others] to deism, and they soon wronged him without moral compunction. Likewise, he came to worry that his own free-thinking had caused him to be cavalier toward Deborah Read and others. In a classic maxim that typifies his pragmatic approach to religion, Franklin declared of deism, “I began to suspect that this doctrine, though it might be true, was not very useful.”

Although divine revelation “had no weight with me,” he decided that religious practices were beneficial because they encouraged good behavior and a moral society. So he began to embrace a morally fortified brand of deism that held God was best served by doing good works and helping other people.”

Well, that only takes you to page 46, but there you go. Honestly, I think this book is one of those must-reads that belongs in every American household, particularly those with teenagers being taught the very limited caricature of Franklin as a mere kite-flying heathen. His life as a printer, public citizen, scientist, inventor, rebel, peacemaker and sage (I use Isaacson’s own chapter titles) is too fascinating, too broad, too inspiring and too damned entertaining to be tossed off so lightly. If my kids were still of an age where I could “share a read” with them (say ages 12-15) I’d be reading to them from this book, nightly, and I know they’d be loving it.

More importantly, if enough Americans read this biography, and find commonality with his pragmatism, we might re-discover within Ben Franklin an important piece of ourselves, and (perhaps) a means of reclaiming for America some characteristics we have allowed others to belittle or redefine?

Buy it. But don’t shove it in your bookcase, as I did, for too long. Read it. You’ll love. If I’m telling you you’ll love, you know you will!

Related:

The Bootstrap Nation; Bill Clinton’s Best Legacy

McCullough’s John Adams (my thoughts)

The Popular Adams (a more scholarly take on McCullough’s book)

John Quincy Adams