I spent part of the Christmas break this year in the (virtual) company of a wonderful tour guide, Michael Martin, whose YouTube series on the metaphysical poets he had made available without paywall “until Candlemas” (that’s Feb 2, to you paynim ).

In the videos, Martin (whose work I’ve written about elsewhere) introduces us to poets we thought we knew — or even disliked — in order to help us hear them for the first time. Beginning with John Donne, the series moves through George Herbert, Richard Crashaw, Henry Vaughan, and (the figure who drew me initially to the series) Thomas Traherne. By the time I’d finished, I could appreciate the comment of Sir Philip Sydney that poets, like God, make worlds.

Thinking of Donne and William Blake in particular, Martin points out that some poets require decades or more before they find their readers — or their readers even begin to comprehend them. But there is something beyond mere comprehension.

These poets, if we give ourselves up to them, attempt to awaken us through a range of strategies, from Donne’s sometimes violent and paradoxical energy (“This is joy’s bonfire, then, where love’s strong arts Make of so noble individual parts One fire of four inflaming eyes, and of two loving hearts”) to Traherne’s blissed-out landscapes (“Your enjoyment of the world is never right till every morning you awake in Heaven; see yourself in your Father’s palace; and look upon the skies, the earth and the air as celestial joys”).

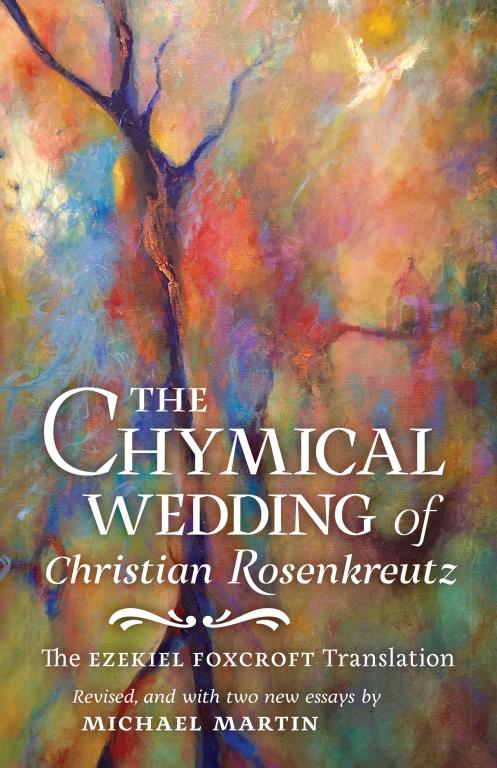

As it happened, I was also reading over the break a review copy of Martin’s new edition of the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, a very curious specimen of … 17th-century fantasy literature? Proto-science fiction? Rosicrucian satire?

As in his brilliant work revivifying the golden thread of sophiology throughout Western tradition, Martin’s commentary here helps us understand how alchemy was once a truly Christian science of regeneration, physical and spiritual. He also points out that the Chymical Wedding is, curiously, a terrible guide to understanding alchemy, given the author’s parodic intentions in concocting this bizarre dream vision.

The text’s larger and more important vision, in Martin’s reading, lies in its meditation on the coniunctio oppositorum that is marriage — between the Bridegroom and the Bride, between God and Sophia, between man and woman. Viewed from a metaphysical angle, the world itself, Martin finally suggests, is a wedding.

If you’re one of those people wondering whatever happened to the Catholic imagination, you may want to skip next year’s inevitable academic conference somewhere on that lugubrious topic to look elsewhere: such as toward the visionary work of Michael Martin.