The upcoming “Economy of Francesco” event (previously described here) in Assisi March 26 – 28 will be a mix of young and old. The 500 attendees will all be age 35 or younger, given the event’s goal of bringing together younger entrepreneurs, business people, economists, and activists eager to discuss an alternative to the dominant neoliberal system.

But the addresses from the many notable speakers — Amartya Sen, Muhammud Yunous, Jeffrey Sachs, Carlo Petrini, Kate Raworth, and others — will highlight the re-emergence of something very old: a social order in which our economic activities are embedded instead of all-controlling. Which in varying degrees is simply the way most of humanity lived for most of time, until the coming of the industrial revolution with its extractive operating system of finance capitalism and its destruction of the commons in the name of growth and new markets.

One historic figure — a saintly if not yet quite sainted one — in this context is Fr. Josemaria Arizmendi, the spiritual and organizational founder of the famous Mondragon cooperative network based in Spain. Arizmendi is becoming well-known in cooperative circles, given the extraordinary history of Mondragon as a successful enterprise somehow not only still operating since its founding in the 1950s but thriving.

If this conversation sounds like mostly a European affair, that’s because we North Americans tend to forget Canadian figures like Fr. Moses Coady and Fr. Jimmy Tompkins, key figures in the Antigonish Movement of the early 20th century.

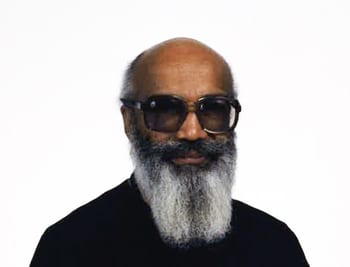

But we may not be aware of a U.S.-born graduate of the Coady Institute, the late Fr. Albert J. McKnight, a remarkable African-American Spiritan priest who passed away in 2016 at the age of 88. Here’s how one obituary described him:

Fr. McKnight was a towering influence on the African American Economic Development Movement in the South. He organized the Southern Cooperative Development Fund (SCDF) and Southern Development Foundation (SDF) to complement the Black Farm Coop Movement of the early 1970s in the South.

Like Arizmendi, Fr. McKnight is another Catholic icon of social justice, one whose life can speak to an American context in which racism enabled economic expropriation for practically the entire history of the U.S.

And his great vision, like that of Arizmendi’s, was largely one of the power of cooperativism, that very old idea. Based in Louisiana, he was also the executive director of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus in which role he brought the spiritual resources of African spirituality into conversation with liturgy and mission, in hopes of an African-American Catholic rite.

At age 66, McKnight wrote an autobiography (PDF version here) called “Whistling in the Wind.” In it he describes receiving an invitation in 1969 from Histadrut, the Israeli labor movement, to visit the cooperatives (called moshav) and kibbutzes in Israel. “The visit … shook my faith in Christianity because I saw people living a communal life — a style unequal to anything I have seen developed by Christians ….”

In the 1970s, McKnight got the idea for establishing family farm cooperative communities in Alabama, Louisiana, and Florida. By the end of the Carter administration, McKnight and his colleagues had four federal agencies committing to sixty million dollars of support for these projects.

“We’ve found that you have to start where people are,” commented McKnight in a video about the Southern Consumer Cooperative, “deal with the problems that they consider urgent, and then that’s how you can get them involved.” Living in southern Louisiana, McKnight also became an aficionado of Cajun culture: the Acadian Delight Bakery was one co-op business started with the help of the SCC. Late in his life, McKnight was still a great fan and supporter of zydeco music.

The white communities — Catholic and non-Catholic — where McKnight attempted to make change were mostly antagonistic to his efforts. He once observed, “The thing that has really amazed me in this whole self-help activity is the hostility that is created and how people feel threatened when poor people start helping themselves. We’ve been accused of being communists, we’ve had motions passed in the Louisiana state legislature to investigate us, the D.A. has raided our offices and seized our books.” (An excellent history of African-American cooperatives is that of Jessica Gordon Nembhard, who covers both the SCDF and the SDF.)

Nonetheless, McKnight and his colleagues pushed on, going beyond helping black farmers finance their operations to other types of cooperatives including printing operations, hotels, radio stations, and even the initial loan that got the popular Cajun/funk-flavored New Orleans-based radio station WWOZ on the air.

From his autobiography: “What we need to do is reinvent the cooperative idea. If ever the cooperative approach was needed, it is today. It’s still a disgrace to Black folks that no place in the country are Blacks in control economically. … We are a people who spend over $300 billion a year. But what do we own? What do we control? … May we have the wisdom, the faith to reinvent the co-op.”