By Dr. Kate Kingsbury and Dr. R. Andrew Chesnut

Since what is now the fastest growing new religious movement which centers on the Mexican folk saint of death went public in 2001 it has faced a formidable foe in the Catholic Church. However the latest crusade against Santa Muerte, dubbed by Mexican clergy “a macabre symbol of the drug trade” and a “satanic cult”, comes from Evangelical Protestants. They have also been inveighing against Santa Muerte for many years now albeit in the shadow of the Mexican Catholic Church, the second largest national church on the planet. On August 23, 2020, American evangelist Philip Blair, an ex-Marine affiliated with Torchlight Ministries, marched to the landmark Santa Muerte shrine in the notorious Mexico City barrio of Tepito, cameras rolling, and began to condemn devotion to death preaching loudly into a microphone. The video went viral and quickly gathered a million views on Twitter. On a crusade, the Evangelist harangued:

“Today is the day of your salvation. You don’t need Santa Muerte. You only need Jesus Christ. Repent for your sins, Tepito. Jesus is life and life conquers death. We speak against the spirit of death over Mexico City. Father God I pray that you would break the power of Santa Muerte over this city and over this land!”

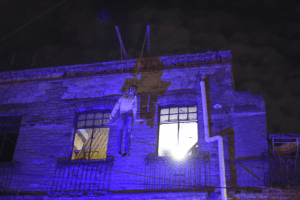

Enriqueta Romero, iconic leader of the Santa Muerte shrine in Tepito with a devotee telling Philip Blair, who stands in front of her, and his camera crew to leave.

HOLY DEATH IN A DEADLY BARRIO

The muscular White evangelist, whose diatribe was being simultaneously interpreted into Spanish by a coreligionist, was driven away from the historic shrine within a couple of minutes. An enraged throng of devotees led by the iconic Godmother and owner of the devotional space, Enriqueta Romero, pushed and hurled epithets at the burly missionary. The mantra shouted by devotees responding to what they saw as a spiritual invasion is “respeto” or respect.

Denied the right to legal recognition as a religious association by the Mexican federal government due to Catholic lobbying and disparaged as working class low-lifes (nacos in Mexican slang), devotees of Death have a poor reputation amongst the minority of Mexican privileged elites. Like Philip Blair, they have little understanding of the spaces of danger, distress and death that the working classes are forced to endure, with little chance of improving their lot. For example, Tepito known locally as the “barrio bravo”, the fierce neighbourhood, is one of the most dangerous districts in Mexico City where even the police don’t dare tread. It is notorious for narco-violence and illegal markets where weapons and drugs are sold. People are often gunned down in broad daylight, caught in the crossfire of gang violence or the victims of a mugging.

NECROPOLITICS, BARE LIFE AND SAINT DEATH

For many, as we have learnt during fieldwork with Santa Muerte devotees, “death is the only thing that is certain”. These are the words of Zaniyah. Her close relationship to an anthropomorphised supernatural depiction of death, in the form of Santa Muerte, allows her to cope with the harsh realities of living in a constant state of precariousness as she attempts to raise a family. Like for so many other Mexicans, existence often hangs by a thin thread in a state where necropolitics and narcoviolence are ubiquitous.

Mbembe coined the term necropolitics to describe a nation-state which knowingly and willingly exposes its citizens to death. This is a space where life as he explains is worth so little, is “so meager…Nobody even bears the slightest feelings of responsibility or justice towards this sort of life or, rather, death”. Such a nation-state complicitly confers upon their citizens “the status of living-dead”. Is it any wonder that if death is the only truth and that citizens are aware of their proximity to death, that a saint of death is now being turned to for life? Devotees supplicate the saint to extend their existence and protect them, given that “living means continually standing up to death” as Mbembe writes, and, in this case trying to negotiate with death for a few more grains of sand in the hourglass of life.

Enriqueta Romero mourns the loss of her husband gunned down in Tepito

Giorgio Agamben has written about “bare life” using the Greek word zoe to describe a situation whereby human life is unprotected and is constantly exposed to death. This, he explains, takes place in a State where the indiscernibility of law contributes to a normative crisis where humans are treated no better than animals and can be subjected to violence and killed with impunity. In Mexico, the working classes, and even many in the middle classes have been reduced to bare life. As Mexican peace scholar Pietro Ameglio Patelli has pointed out, in the nation-state most citizens are reduced to an “unprotected life, … a being that can be subjected to violence, kidnapped, ill-treated or humiliated and murdered with impunity”.

A POST-CATHOLIC RESPONSE TO THE PRECARITY OF THE POST-COLONY

The Mexican murder rate in 2019 reached an all time high, with 35,000 confirmed homicides. Furthermore, as a result of the drug war 65,000 people have vanished since 2006, confirming that the president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador`s policy towards narcos, summarized in his maxim “abrazos no balazos” (hugs not bullets), has been ineffectual. Femicide and gendered violence in Mexico is a dire problem. 1000 women were killed so far in 2020. The figures keep rising as COVID quarantine has led to a sinister surge in domestic violence. Government figures note an increase in femicides of 137% in the past three years but all this is met with impunity. It would be apposite to coin the term “gyno-necropolitics”, to speak of the Mexican nation-state which implicitly grants men a license to kill women. In response to this surfeit of violence, a post-Catholic folk faith has emerged. Santa Muerte is a form of post-Catholic “alter-cultural praxis”, to use McNeal’s term, that both takes from Catholicism but also subverts its doctrine in order to adapt it to the current context of bare life.

Santa Muerte’s followers come from a wide range of backgrounds, and female followers and leaders have notably been at the centre of the movement given that women are among the most excluded and imperiled demographic in Mexico. Devotees are always to be found in the most impoverished and marginalised groups, and those whose lives are constantly hanging in the balance, from drug addicts, sex workers, prisoners to members of the gay and transgender communities. The destitute live in dangerous neighbourhoods, like Tepito, where death is part of everyday life. The desire to worship death comes in part from the need to accept death, in order to place a familiar face on and not be fearful when confronted with what many dread. The poverty-stricken also pray to Santa Muerte for a holy death (one of her English translations); namely a natural end, as opposed to one caused by criminal brutality. They believe it will be easier to traverse purgatory and get to heaven if their soul is not tormented by violence.

Many devotees have grown up in Catholic households and identify as Catholic, but find the faith offers them no solace in the face of or means to cope with so much “mala muerte” (bad death). Mothers, for example, marginalised from political spheres and unable to express their fears and anger in the public space, suffer from fear, stress, depression and anxiety as heads of household trying to bring up children and protect themselves in the face of so much violence. Many have had to cope with the death or disappearance of their children. Some women have been victims of violence themselves and find in the Catholic faith no means to legitimise their identities and suffering as women. Santa Muerte which centers around a powerful female figure who is said to understand and attend to the difficulties of women and mothers offers them a means of expression and validation. It further places value on the female body and experience. This is rare in a country where the government turns a blind eye as women and girls are mutilated and murdered daily and then tossed out like waste at garbage dumps.

Other devotees, due to the nature of their profession or their sexual orientation may be aware that they are not welcome in the Catholic Church, and fear that God might judge them for the sins they have committed. Death, however, as personified by Santa Muerte, does not judge, according to her followers. This is an inclusive faith. Whether one is gay, bisexual or straight, a recidivist or a law-abiding citizen, rich or poor, death comes to us all. Therefore, followers believe that Santa Muerte listens to everyone’s prayers no matter who they are. Moreover, the marginalised relate to the folk saint due to her ostracism by the authorities.

A CRUSADE AGAINST DEATH

While both Evangelicals and the Catholic Church in Mexico have been rebuking Santa Muerte for more than a decade now, the American evangelist’s aggressive intrusion into what is really the most sacred space for the fastest growing new religious movement in the West represents an escalation of the crusade against the female folk saint. A former Marine, Blair, has channeled his training in military battle into spiritual warfare. Spiritual warfare in which all other religions beyond Protestantism, especially of the Evangelical variety, are considered demonic and thus must be combatted, is all the rage among Evangelicals, particularly Pentecostals, across the globe.

In the past few days Blair’s Youtube video has gone viral on social media provoking polemical responses which led him to tweet on August 28, “Dear people who don’t like me but still sharing the videos: you’re helping us spread the good news of Jesus Christ whether you know it or not. So in that, I say thank you. Santa Muerte is a false god full of demons and curses. Only Jesus brings life. Repent while you can. #Tepito.”

In Brazil Pentecostal gangsters terrorize practitioners of Umbanda and Candomble, the two main African diasporan faiths, while in Guatemala a Mayan spiritual guide was burned alive by local Pentecostals who accused him of witchcraft. In Mexico and across Latin America the recent prominence of spiritual warfare is in large measure a function of the meteoric growth of Pentecostalism over the past 5 decades to the extent that many nations in the most Catholic region on earth are no longer majority Catholic, such as Brazil, Guatemala, Honduras and others.With presidents of the two largest nations in the Americas, Trump and Bolsonaro, claiming Evangelicals as their political base, these fundamentalist Protestants feel newly empowered to do battle with the forces of darkness. As a female skeletal personification of death often erroneously associated only with drug cartels, Santa Muerte is the poster girl for evil incarnate for many who do not understand the context of devotion to death. While those who regularly attend Catholic churches and follow papal pronouncements might be dissuaded from devotion to Santa Muerte, those at the margins of society who face danger and death daily, or whose lifestyle choices jar with those extolled by the Church, may not be persuaded to, or be able to, abandon either their way of life or their faith in the folk saint of death, whose bony embrace and final kiss of death, as they well know, is never far away.