Jointly authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury*, David B. Metcalfe**, and Dr. Andrew Chesnut

The season of death is upon us. October is here impending Halloween with its cavalcade of crones, ghosts and goblins together with the Catholic holy days of All Saints and All Souls, known in Latin America as Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) on November 1st and 2nd. Included in these fall festivals are two familiar faces whose skeletal visages afford them special attention during the season, despite the fact that neither one is historically connected to these holidays. Santa Muerte (Saint Death) and la Catrina Calavera (the Skeleton Dame) engage not only millions of North and South Americans but also many Europeans in rituals that reconnect us with our own mortality.

With retail outlets across the U.S. featuring more and more Mexican-themed Day of the Dead and Catrina items in their Halloween merchandise, we’ll leave aside the trick or treating and pumpkin carving of our own childhood in the United States or the vicars and tarts parties of the UK, and try to answer one of the two questions that invariably come up during our presentations on Day of the Dead and the White Girl (one of Santa Muerte’s main monikers). What is the rapport, if any, among the three iconic figures of Mexican death culture – Catrina Calavera, Santa Muerte, and Day of the Dead?

SANTA MUERTE

The first member of the Mexican death trinity has been in the limelight during the past decade or so, especially with her appearances in numerous TV series such as Penny Dreadful and Breaking Bad, and movies, such as Bad Boys 3, for which Kingsbury and Chesnut served as expert consultants. Santa Muerte is a Mexican folk saint who personifies death in the form of a female skeleton. Whether as a gold medallion, or statuette, or votive candle she is typically depicted as a Grim Reapress, wielding the same scythe and wearing a shroud similar to that of the Grim Reaper, her male forebear. Unlike canonized Catholics, folk saints are believed to be spirits of deceased Latin American women and men considered holy for their miracle working powers. What really distinguishes the White Girl, however, from other regional folk saints is that for most devotees she is the personification of death itself and not of a real woman that lived and died on Mexican soil.

In Mexico and Latin America in general, folk saints such as San La Muerte (the Argentine male cousin of Santa Muerte), Jesus Malverde, and Rey Pascual (the Guatemalan male cousin of the White Girl) have millions of devotees and are often sought out more than the thousands of Catholic saints, most of whom are Europeans who lived centuries ago. These grassroots Latin American saints are united to their devotees by nationality, culture and often class. Explaining the appeal of the skeleton saint a Mexico City street vendor stated, “She understands us because she’s a badass (cabrona) like us.” In stark contrast, Mexicans would never refer to national matroness, the Virgin of Guadalupe, as a cabrona, which is also often uttered to mean “bitch.”

Santa Muerte is prayed to for miracles by a wide demographic of devotees. Depending on the colour of her gown or the votive candle bearing her name, she offers different favours. In her ebony gown, she is known for bringing death to enemies, and in her red mantle she aids women and men with love and lust, whilst dressed in ivory, the Bony Lady brings peace, well-being and cleansing. In her gold gown she brings wealth and abundance and in her green garb she offers her aid with legal matters. In her purple cloak she brings health and healing, for example against COVID-19. Her blue mantle represents aid with studies, imparting wisdom in academic and other intellectual affairs

Dispelling the popular misconception that the skeleton saint’s official “feast day” is August 15, most of the major shrines in the U.S. and Mexico celebrate annual feast days with the specific date varying and often on the day they were founded. For example, Doña Queta’s historic shrine in the notorious Mexico City barrio of Tepito will commemorate its nineteenth anniversary on Halloween of this year. However, if there is a feast day in the future it will likely be November 2, Day of the Dead, as one of the most salient recent devotional trends is that of devotees incorporating Saint Death into their Dia de los Muertos commemorations. This has become so popular that Catholic bishops and priests across Mexico and even some in the U.S. routinely remind parishioners in the weeks preceding Day of the Dead that Santa Muerte stands in opposition to Christian beliefs and as such should under no circumstances be part of the remembrance of deceased family members and friends. Nevertheless, as Kingsbury experienced in Oaxaca, some even turn to their deceased relatives, beseeching them at their grave sites for permission to attend Santa Muerte celebrations.

DAY OF THE DEAD

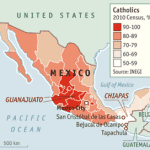

In the U.S., the Catholic festival of All Hallow’s Eve has taken on the darker image of Halloween, with haunted houses, horror movies, and the departed returning for trouble rather than tradition. In Latin America and Europe, where Catholic cultural influences have remained relatively strong, the first and second of November continue to hold their ancient ties to festivals associated with honoring, celebrating and continuing interaction with the dead. In Mexico, before the Spanish conquest, the Aztecs dedicated most of the month of August to their goddess of death, Mictecacihuatl. While today’s celebrations are less extensive – Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead,) which falls on November 1 and 2, is one of the most anticipated holidays of the year. It’s a time to reconnect with deceased family members, ancestors, and friends in a convivial spirit of remembrance and celebration.

As part of the overarching suppression of Indigenous religion, the Catholic Church exorcised Mictecacihuatl and moved the date to coincide with All Saints’ Day (November 1), which is also known in Mexico as Day of the Innocents for its association with Masses focusing on deceased infants and children, and All Souls Day (November 2), where the focus is on departed adults.

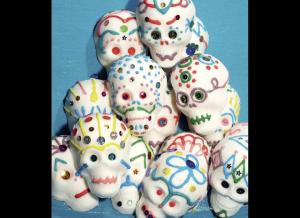

Visits to the cemetery to bring offerings to the dead, such as candles, flowers -especially Cempazuchitl, the distinctive yellow marigolds-, and food, are common, along with offerings left at home altars. These are erected to honour the deceased. They are symbolic expressions or representations of the departed and the love that the living still have for them. These altars consist of a photo of the dead surrounded by their favourite objects which are given as offerings, to welcome them and show these souls that they have not been forgotten. Children typically receive toys, candy, sweet tamales, fruit, and other such victuals. Adults receive libations of their favourite alcoholic beverages, such as Mezcal in Oaxaca. They are also offered their preferred dishes, and possibly cigarettes. In graveyards and on altars they are also given the striking sugar skulls, calaveras de azúcar, and pan de muerto (bread of the dead), which will be recognized by many readers outside of Mexico as familiar icons of the tradition. Adorned with the name of a deceased relative, the skulls are eaten as a reminder that death is not a bitter end, but rather a sweet continuation of the natural cycles of life.

Historically commemoration of Day of the Dead has been more common among working class Mexicans. However, the combined influence of the James Bond film, Spectre, and the immensely popular animated movie, Coco, along with growing popularity in the U.S., has led many middle class Mexican urbanites to embrace traditions they used to ignore or even deride. In a surreal case of life imitating art, Mexico City held its first Day of the Dead parade last year, which strongly resembled the opening scenes of Spectre. In a similar vein, some of Chesnut’s Mexican relatives in Michoacan, a state famous for its colorful Day of the Dead commemorations, only began erecting home altars after seeing Coco!

From the home hearth to the world stage the imagery of Dia de Muertos has become an able ambassador for Mexico’s cultural heritage around the globe! Nevertheless it should be noted that the middle class of Mexico City generally treat the event as an excuse for revelry and dressing up in neo-Mexi-gothic garb as opposed to the Indigenous peoples of Mexico, who don their huipil, engage in solemn processions and for whom the event is steeped in traditions that are jovial yet suffused with sadness as mariachi bands play the favourite songs of the dearly departed.

SKELETON DAME

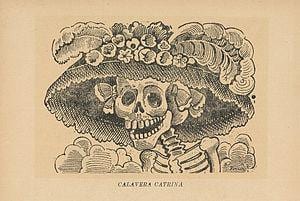

La Catrina, the Skeleton Dame, is often confused by the unfamiliar with the Skeleton Saint, Santa Muerte, but they are very different figures. While the former issued from a satirical drawing, the latter is a figure of spiritual reverence. La Catrina originated in 1910, from the pen of José Guadalupe Posada who is considered the father of Mexican print-making. Posada was a contemporary of the Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz who ruled the country for 31 years. Despite modernizing Mexico, he was notorious for peculating, and operated a repressive regime that oppressed the lower classes. He and his entourage maintained a lavish lifestyle forming a privileged Eurocentric elite in a country where many were starving to death.

Posada wielded his artistic skills in an act of insurgency, producing images that communicated his dissatisfaction with the regime. His use of these allowed his ideas to be instantly understood, including by the numerous illiterate Mexicans. The satirical cartoon of la Catrina was created to mock the ruling classes. La Catrina, also known as “La Calavera Garbancera” (the Dapper Skeleton), was originally a black and white zinc etching of a skeleton attired in a large French-style floppy hat. It is said that she was drafted in the likeness of the dictator’s wife, Carmen Romero Rubio.

Posada’s popular illustrations were deeply embedded into the cultural context of the Mexican Revolution (1910-20), the first great popular revolt of the 20th century, which led to a new appreciation of the Indigenous past. The symbolism of the skeleton, which in Indigenous traditions throughout the Americas represents the continuation of life’s cyclical turn, proved to be a potent and resonant image for Mexican cultural independence from its Eurocentric elite. An ironic origin considering her contemporary role symbolizing the integration of pre-Hispanic and post-colonial ideals.

La Catrina was one of thousands of sketches of skeletons garbed in European finery that derided the vanity and opulent lifestyles of the upper classes whose extravagances were at the expense of the suffering lower classes. The message Posada was conveying was that no matter one’s wealth or status, no one escapes death and indeed the phrase “todos somos calaveras” (we are all skeletons) is often attributed to the illustrator. In this manner, la Catrina resembles Santa Muerte in that she serves as a reminder of the inevitability of death, however beyond this there are no further similarities apart from that both are female skeletons.

Given that the skeleton motif has deep roots in Mexico, the image of La Catrina resonated deeply with the public and with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera who altered the image of La Catrina. He morphed her into a mestizo symbol that amalgamated pre-Hispanic, colonial and postcolonial thanatological mythemes in his famed 1948 mural Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park in which he depicted himself as the son of la Catrina and Posada. Since that time innumerable iterations of the skeleton dame have been fashioned, and in keeping with Riviera’s use, la Catrina has morphed from a satirical symbol into one of national pride.

In the 1980s, three-dimensional statuettes of la Catrina began to appear on sale, largely bought by tourists and affluent Mexicans. These are still popular. La Catrina has also since this time become widely used in commercialized Day of the Dead celebrations. Unlike Santa Muerte who though sometimes dressed in spangly gowns may also be depicted as austere, La Catrina is always frivolously clad, usually in a flashy frock, often clutching a purse or a parasol and always bedecked with her trademark flamboyant, floppy hat. Today, she remains an important icon of Mexican national identity, and speaks to the unique and fruitful cultural dialogue which continues in Latin America.

LA MUERTA FESTIVA

Mexican culture is not alone in its remembrance of death, but it is unique in how, more often than not, these commemorations mingle the festive with the funereal in an interplay of joviality and sorrow, evincing an understanding of life and death that is more nuanced than that we often encounter in the West. Whether it is under the scythe of Santa Muerte during the festivities of Dia de los Muertos, or in the “elegant” image of Calavera Catrina, death plays a central role in the daily lives of Mexicans and continues much as in the pre-Hispanic past, to provide a potent image for the inevitable cycles of life. Running through it all is a sense of humor and empowerment, which takes the hard lessons of death and embraces them with a fullness that is often surprising to those unfamiliar with these traditions.

Recalling pre-Columbian traditions, death remains an image of rebirth and renewal. The imagery and practices associated with these traditions keep the memory of a turbulent history alive. From a multitude of diverse Indigenous peoples in a territory that was torn limb from limb by the Spanish to line their pockets, to today, a nation with dire disparities between rich and poor and a plague of narco-violence which obliterates the lives of the innocent and the criminal every nanosecond. Nevertheless, death perdures as the great equalizer, in which everyone from incarcerated drug baron El Chapo to billionaire impresario Carlos Slim will inevitably succumb to Santa Muerte’s leveling scythe.

As they say in Mexico, “death is just and even-handed for everyone, since we will all die.” For many, this unalterable truth provides a strong reason to celebrate life while there is still time but also to bask in the knowledge that death will bring an end to us all, rich or poor, male or female, young or old.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford and is author of the forthcoming “Daughters of Death: The Female Followers of Santa Muerte” with Oxford University Press. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda.

**David Metcalfe is a researcher, writer and multimedia specialist focusing on the interrelationship of art, culture, and consciousness. He is a contributor at SkeletonSaint.com and Editor-in-Chief for the Windbridge Research Center’s Threshold: Journal of Interdisciplinary Consciousness Studies. Follow him on Twitter.