Over the past couple of months I’ve occasionally posted my reflections from an experience I had with The Global Immersion Project. If you want to read other reflections, check out: “A Land Without a People for a People without a Land?” or “The Art of Resistance: Bansky, Memory, & Hope.” I should simply add that TGIP continues to make an impact on my life, both my personal reflections and my guidance of our new church. In fact, I hope to take another trip with TGIP in the near-future. This trip would primarily be for leaders within my faith community, but would involve a few others as well. All of that to say: if you want to visit the Holy Land and if you want training in active peacemaking – TGIP is THE organization to go with!

————————————————————————————-

The next Dr. King or Gandhi lives in Palestine.

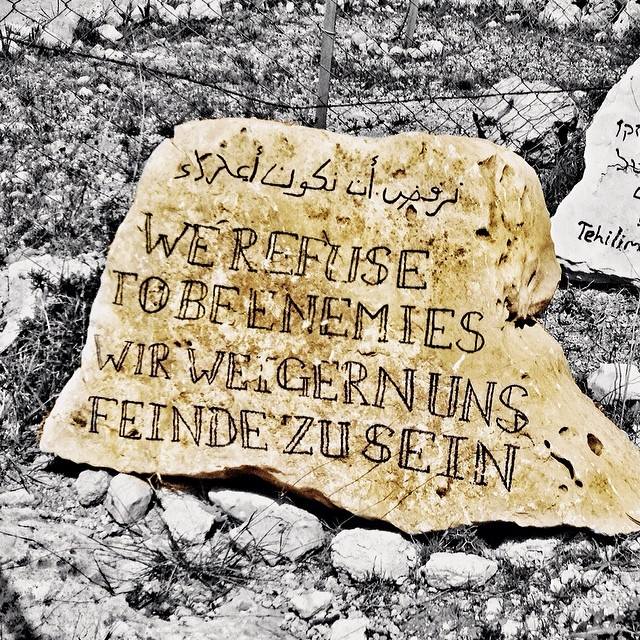

One of the peacemakers that we got to know on our trip to Israel/Palestine was Daoud Nasser. His family has owned the same hill in the West Bank since 1916! In fact, this is the last Palestinian owned hill – anywhere. They have the ownership papers to prove it, traced back all the way to the Ottoman Empire. As a result, they have been in court with Israel since 1991. Through seasons of persecution: military vehicles coming on the property bearing a threatening presence, Israeli settlers coming with guns and acting out in violence, olive trees being torn down, being unable to get building permits and running water, and more – they have maintained this slogan:

We refuse to be enemies.

-Tent of Nations

They are, in a beautiful sense, what Jesus was getting at when he talked about “a city on a hill” by refusing hatred and instead choosing to “love [their] enemies.” With this beautiful gift of the hill, they house an organization called Tent of Nations. Among several ministries, Tent of Nations teaches about peacemaking, hosts creative camps for children, cultivates the land through eco-friendly means, and develops methods for harnessing power and water since the government refuses to give them access to such necessities. On top of this, when they are persecuted they choose to go through the legal system – tilted against them – to humbly expose injustice while loving their oppressors! They model something that Jesus clearly taught in the Sermon on the Mount: that enemy love is central to the message of the Kingdom of God. For Daoud and his family, how they react to persecution reflects the God that they serve. The Sermon on the Mount is a source for funding their imagination.

Options for Responding to Oppression

In Matthew 5, Jesus declares that the peacemakers are “blessed” (fortunate or happy). Later in verse 38 we are given the Hebrew Bible command “eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.” It is commonly noted that such a law was a preventative measure to ensure that punishment was proportional to the crime, and no more.[1] “Where the Torah restricts retaliation, Jesus forbids it all together.”[2] This is clear by his exhortation that disciples are called to “not resist an evil person.” Is Jesus saying that one must not resist at all?

For Palestinian people, they have had several responses to the situation under the Israeli Occupation. One option is to embrace that the only hope left is violence. But, as I’ve heard Daoud say in person: “Violence only creates more violence.” The second group chooses a posture of victimhood. They see no options beyond their despair and are rendered passive. The third group, many of whom are part of the Christian minority, find ways to leave the country so that they have a chance at a better life. But, in leaving, they escape a situation that might be made better by their presence. This is where Daoud and his family come in. Inspired by Jesus and the early church, and secondarily by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi, they are choosing a path that cuts through passivity and violence: nonviolent resistance. This is, from what I can tell, the New Testament model of resisting injustice, occupation (lest we forget that Israel was also Occupied in Jesus’ day by an oppressor), and violence.

It is interesting to note that the Ancient Greek (the language the New Testament was originally written in) word for not resisting is: ἀντιστῆναι (antistēnai). The way that this word is translated in Matthew 5.39 (“Do not resist an evildoer”) gives the impression that any form of resistance is unacceptable. If this is indeed the case, then nonresistance is the more faithful term to describe the New Testament position against violence. But, Jesus chose a specific word that has a deeper meaning than is often attributed to it. Walter Wink helpfully points out that “antistēnai… means to resist violently, to revolt or rebel, to engage in an armed insurrection.”[3] So, to be clear, Jesus is using a word that means resisting through violent means and negating it! This differs from a passive posture but simultaneously forbids using dehumanizing violence.

Support for this translation is not unwarranted as antistēnai is the word repeatedly used in the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible as “warfare” and is also used in Ephesians 6.13 in the context of active military imagery.[4] In the famous “armor of God” passage the rhetoric clearly indicates an offensive military-like “stand” that is able to both pursue and undo the works of the powers of evil.[5] Wink’s argument is further affirmed by N.T. Wright who translates verse 39 in the following way: “But I say to you: don’t use violence to resist evil!”[6] Jesus “is telling us to transcend both passivity and violence by finding a third way, one that is at once assertive yet nonviolent.”[7] Daoud and the Tent of Nations exemplify this approach!

Jesus invites his followers to choose nonviolence in a world of violence. This may seem irrational for some, but it is one of the central aspects of what it means to be a disciple. He takes it further than nonviolent resistance when he also invites us to “love your enemies” or as Tent of Nations says: “We refuse to be enemies.” Peace means that we become a people who love everyone, even the people we might be inclined to hate. Tent of Nations models this for the world to see. They are a “city on a hill” that “cannot be hidden” (Matt. 5.14) – which is especially true now when 50,000 Israeli settlers surround them.

Peacemaking: From Abstract Controversy to Concrete Realism

For us (or at least me) in the USA, the concept of enemies is often hard to grasp. We may spend our time arguing about whether or not Jesus actually taught absolute nonviolence or if it was some sort of “ideal” versus the “real.” It gets even more complex as we start our conversations from the worst case scenarios (What about a rapist attacking your wife? What about Hitler?) and then work our way up toward the biblical text rather than starting with Jesus’ own words and letting that inform our normative understanding of his teaching. Even more, when we don’t deal with real flesh and blood enemies on a daily basis it’s easy to leave these difficult conversations in the clouds of theory.

For Daoud Nasser, this isn’t an option. For him, choosing the nonviolent resistance model of Jesus and loving his enemies is a concrete practice.This, of course begs a question: What if we simply started experimenting with peacemaking (or perhaps an easier word to grasp that isn’t so controversial theologically is reconciliation) in our neighborhoods and cities? I think this is one thing that Daoud’s example invites us into, and this is certainly what I learned during my total time with The Global Immersion Project (I’ll say more about this in later posts). Perhaps how this Palestinian Gandhi or Dr. King beckons us to respond is by choosing to see how we can be agents of reconciliation in tangible ways. This starts by seeing that conflict is all around us and by believing that a better way is possible – for the Palestinian people and for us, wherever we live.

The next Dr. King or Gandhi lives in Palestine, but what if the next Dr. King/Gandhi also lives in your neighborhood? Perhaps it will also be you.

Two Videos to Check Out:

The Tent of Nations from Christ at the Checkpoint on Vimeo.

Love Your Enemies from The Austin Stone on Vimeo.

[1] Richard B. Hays, The Moral Vision of the New Testament: Community, Cross, New Creation: A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996), 324.

[2] Ibid., 325.

[3] Walter Wink, The Powers That Be: Theology for a New Millennium (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 100.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Thomas Yoder-Neufeld, Ephesians, Believers Church Bible Commentary (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 2002), 294-95.

[6] Tom Wright, Matthew for Everyone, 1 (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2004), 49.

[7] Wink, The Powers That Be: Theology for a New Millennium, 101.