Micah is a very complicated book, and has engendered no end of attempts to solve its myriad difficulties. We think of it as the work of an 8th century BCE prophet, contemporaneous with I-Isaiah, probably living somewhere in the Judean countryside, just before or just after the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel to the Assyrians in 722 BCE. He is a crusty fellow, who views the city of Jerusalem and those who inhabit it with an especially jaundiced eye. You have to like anyone who could get off a line like 2:11: “If someone were to go about uttering trivial lies, saying, ‘I will preach to you of wine and strong drink,’ one like that would be just the preacher for this people!” While justice is being avoided, and the poor are being abused, Micah claims that the people would rather hear of anything from their religious leaders—even a sole focus on the dangers of alcohol abuse—than be confronted by the truth of their own indifference to the true horrors of their unjust society. Nearly every reader of the Bible knows the unforgettable lines from 6:6-8 where the prophet defines about as clearly as anyone ever has what YHWH wants for the chosen people, namely, “to do justice, to love chesed (that is, to love as YHWH loves, freely and inclusively), and to walk resolutely (I find the usual reading “humbly” to be finally misleading and overly romantic) with your God.” That, I have long believed, summarizes the prophecy of 8th century Micah.

Micah is a very complicated book, and has engendered no end of attempts to solve its myriad difficulties. We think of it as the work of an 8th century BCE prophet, contemporaneous with I-Isaiah, probably living somewhere in the Judean countryside, just before or just after the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel to the Assyrians in 722 BCE. He is a crusty fellow, who views the city of Jerusalem and those who inhabit it with an especially jaundiced eye. You have to like anyone who could get off a line like 2:11: “If someone were to go about uttering trivial lies, saying, ‘I will preach to you of wine and strong drink,’ one like that would be just the preacher for this people!” While justice is being avoided, and the poor are being abused, Micah claims that the people would rather hear of anything from their religious leaders—even a sole focus on the dangers of alcohol abuse—than be confronted by the truth of their own indifference to the true horrors of their unjust society. Nearly every reader of the Bible knows the unforgettable lines from 6:6-8 where the prophet defines about as clearly as anyone ever has what YHWH wants for the chosen people, namely, “to do justice, to love chesed (that is, to love as YHWH loves, freely and inclusively), and to walk resolutely (I find the usual reading “humbly” to be finally misleading and overly romantic) with your God.” That, I have long believed, summarizes the prophecy of 8th century Micah.

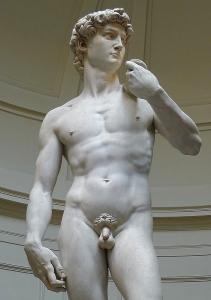

But today’s text from Micah 5 may be from another era altogether, or so many scholars have concluded. I am not so certain of that conclusion myself, but whenever it was composed, it has offered early Christian readers one of those classical places in the Hebrew Bible where Jesus has been easily and readily ushered in as the one who is referred to. After all, we all know where Jesus was born—“O Little Town of Bethlehem”- -, and though that town has become the center of the Christian story, and though it has long been an out of the way village, surrounded by fields and farms, “one of the little clans of Judah,” as Micah puts it, when the prophet uttered this oracle, or perhaps one of his followers uttered it, Jesus did not come to anyone’s mind. But we can certainly say who did: the great king David. David, by the time of Micah, remembered as the greatest King in the history of Israel, was born and, unlike Jesus, was also raised in Bethlehem, the eighth son of Jesse who became through grit and luck and the power of YHWH the second king of the land. The mention of Bethlehem on the lips of Micah clearly refers to the mighty name of David.

Yet, there is mystery here, of course, since the great David has been dead for over two centuries, and Micah promises “one who is to rule in Israel, whose origin is from of old, from ancient days” (Micah 5:2). Apparently, what Micah has in mind is one very like David, or at least one who will recapture the halcyon days that David’s reign calls to the prophet’s mind. What the oracle promises at its close is shalom; this one to come will be “one of shalom,” says Micah. Now what might that mean in this context?

The word “shalom” does not quite mean “peace” in the way we usually translate the word into English. Micah does not here refer to the hope for peace as the absence of conflict. The basic meaning of the root of the word is rather “unity, wholeness,” something closer akin to “security,” a word that appears in the NRSV in 5:4: “They shall live secure.” Actually, no word like “secure” exists in the Hebrew of this line. A more literal meaning would be “they shall live because now he will be great.” By implication, as the NRSV translators assumed, the word “live” includes within its use here the idea of security and safety. What this mysterious person from Bethlehem will provide, promises Micah, is safety, a peaceful existence free from the terror of the times. This is no romantic portrait of “wolves lying down with lambs,” as Isaiah has it, but a time free from the threat of Assyrian assault, those same Assyrians that have just effected the sack of Samaria—or are about to do so.

At Micah 5:3a, there is a hint of the far more famous promise found in Is.7:14 where “a young woman is about to conceive and bear a son,” followed by the obscure reference to a subsequent time when the threats to Judah will subside before the leaders of Judah’s enemies can do their worst. We all know what Christian commentators did with that reference, making of it a prefiguring of the virgin birth of Jesus, at least according to Matthew and Luke. Micah, far more peculiarly, says “Therefore he will give them up (or “offer them”) until the time when she who is in labor gives birth.” And after the birth, “the remnant of his kin shall return to the people of Israel.” I admit that I cannot make hide nor hair of what this might mean. Is the “he” YHWH” or the one from Bethlehem, from of old? However one adjudicates that conundrum, the Bethlehem figure will now “feed his flock (a David picture again?) in the strength of YHWH, in the majesty of the name of YHWH his God.” “He will be this peace,” reads the end of the oracle quite literally.

We know what happened with this obscure oracle in the New Testament. At Matt.2:6 the gospel writer puts part of the Micah proclamation in the mouth of Herod’s chief priests and scribes when they are asked by the disturbed king where Messiah is to be born. “In Bethlehem,” they reply, quoting Micah, though Matthew plays with the text a bit by claiming that Micah has said that this Messiah will “shepherd my people Israel,” while Micah plainly does not say that so directly. Later in John’s gospel, Jesus is called Messiah by some who hear him, but others say that Messiah does not come from Galilee, Jesus’s origin place, quoting Micah who announced that Messiah must come from Bethlehem, “the village where David lived” (John 7:42).

Perhaps this convoluted textual history may be summarized as follows: Micah promises to his troubled and terrified people, standing in the face of potential Assyrian annihilation, a new ruler from the fabled Bethlehem who will provide for them what they so earnestly hope for, namely security, freedom from fear, hope for a future with YHWH. The early Christians hoped for something quite similar when they hooked their star to Jesus of Nazareth, a new leader from Bethlehem who they hoped would give them safety and security in the face of Roman power and threat. His death at the hands of those same Romans forced them to rethink what this particular Messiah actually offered them. And that redefinition of what Messiah did, and can do, has been the work of Christian thought ever since. Jesus the Messiah was not a new David after all, not a bringer of safety, not a warrior who stands against the powerful ones of every day and time. Though Christians through the ages have often made Jesus into that image, a man of power ready to smite his enemies, to right the wrongs of a perpetually unjust world, he remains not that Messiah at all. Christmas reminds us of that fact each year, as we gather at the manger, not in the halls of a palace, not in the war room of advanced military might, to welcome him once again. Just what sort of Messiah a helpless baby might be is left to each of us to determine. That determination I leave to each of you and wish you a very merry Christmas!

(images from Wikimedia Commons)