Recently, my wife and I attended a performance of Gustav Mahler’s massive Symphony #2, known as the Resurrection symphony. By any measure this is a monumental work, requiring an extraordinarily large orchestra with multiple percussion (including steel rods (!) and a huge bell), 6 French horns (plus two more in an offstage ensemble), and on and on. The Los Angeles Philharmonic, under the baton of the venerable Zubin Mehta, now 83 years old, played the work beautifully, especially the shattering last movement, complete with the Los Angeles Master Chorale singing, well, masterfully, and soprano and contralto soloists adding immeasurably to the whole. It was a great evening of music making of the highest order. This piece is clearly Mahler’s most popular and accessible work, and remains for me one of the most effecting works in all of classical music. And seeing it live is imperative for its full impact.

Recently, my wife and I attended a performance of Gustav Mahler’s massive Symphony #2, known as the Resurrection symphony. By any measure this is a monumental work, requiring an extraordinarily large orchestra with multiple percussion (including steel rods (!) and a huge bell), 6 French horns (plus two more in an offstage ensemble), and on and on. The Los Angeles Philharmonic, under the baton of the venerable Zubin Mehta, now 83 years old, played the work beautifully, especially the shattering last movement, complete with the Los Angeles Master Chorale singing, well, masterfully, and soprano and contralto soloists adding immeasurably to the whole. It was a great evening of music making of the highest order. This piece is clearly Mahler’s most popular and accessible work, and remains for me one of the most effecting works in all of classical music. And seeing it live is imperative for its full impact.

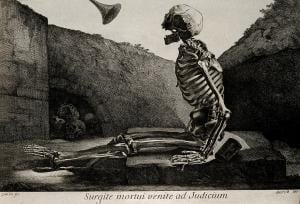

Like Beethoven some 70 years before him, Mahler incorporated a huge chorus into his final movement, along with vocal soloists, to provide a rich texture for what he envisioned as the climax of a narrative of death to life. Mahler, who publicly stated more than once that he disliked the concept of “program music,” that is a narrative scenario to accompany a musical offering, clearly had something of a program in mind for his second symphony. The first movement, that he entitled “Todtenfeier” (“funeral rite”) he imagined as the funeral ritual of the hero of his first symphony, known as “The Titan”. In fact, this quite extensive first movement Mahler at first thought would be an independent piece, and not the beginning of a symphony at all. Yet, in time he realized that that music called for more, and he composed two more movements to accompany the work; he even presented this three-movement work first in 1895 before directing the five-movement symphony some months later.

Mahler had a difficult time coming to exactly what he wanted as the finale of his symphony. The famous conductor, Hans van Bulow, an early admirer of the young Mahler’s music, died in 1894, and at his funeral a choral setting of a poem by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) was sung. The poem was entitled “Auferstehung” (“Resurrection”), and Mahler left the funeral and rushed home to begin work on the final movement, inspired by Klopstock’s poem. Klopstock was a deeply pious man, and fully accepted the traditional Protestant belief in the resurrection of Jesus and the subsequent resurrection to eternal life of his followers. Of course, Mahler was a Jew and a generally secular Jew at that. He in no way possessed a Christian belief in resurrection, traditional or otherwise, but he did possess beliefs that could perhaps be judged pantheistic where all have come from God and will at the last return to God. In what precise forms that return will be accomplished was for Mahler of no real consequence. This fact is made clear by the use Mahler made of Klopstock’s poem. He incorporated only the first two stanzas, even changing one of the lines of those stanzas, while adding six new stanzas of his own. It must be realized that the end of Mahler’s symphony #2 is not at all a musical rendition of traditional Christian belief in resurrection, no matter how a traditional Christian might wish to believe that it is, so powerful and moving the music obviously is.

The closing portion of the symphony includes the following words:

“Rise, yes, you will rise, my heart, in the twinkling of an eye! What you have fought for will lead you to God!”

Among those things that “the heart” has fought for is “what you have loved” as the contralto sings earlier in the movement. Also, the heart has struggled with “pain, the piercer of all things,” that the duet of solo voices announces, too. Mahler, all of his life, suffered numerous physical ailments, and ended his life at 51 due to a fatal condition of the heart. Surely, he imagined in his symphony that his heart would eventually find its way free of pain back to God, whom he names in the poem “Urlicht,” or the “primal light,” sung by the contralto in movement 4.

This return to God will be made possible, in Mahler’s own words, “with wings that I have won for myself in love’s fierce striving.” On these wings Mahler envisions a “soaring upward to the light where no eye has soared.” As you can see, we are far from traditional Christianity here, the belief that the resurrection of Jesus has won for us a path to our own resurrection to eternal life. Not so, says Mahler. It is our own striving with love in our lives that may gain for us a return to God at the last. Right here I find suggestive ideas for my own struggle with the notion of resurrection.

I find the typical and now wide spread view of resurrection quite trivial, a sort of feel-good belief that we all will see our loved ones again in some far-away heaven. And that was all made possible by the resurrection of Jesus, whose own eternal life promises to bring his followers along with him to the eternal throne of God. This viewpoint has been made manifest in most modern memorial services where all gathered are assured that, like the deceased who is now playing in a Godly heaven, so will we all join her in eternal golf, or bowling or knitting or whatever it was she enjoyed while living among us. What these ideas avoid is what stands at the center of any belief in the defeat of that final master, death, namely the conviction of God’s power and fidelity in the face of every negation. It is in our comfortable modern church common to be wary of any “unnatural” notions of death’s defeat by God, because we have a very hard time coming to grips with any God of genuine power who rules over our lives and over our easy accommodations to the world and its pleasures and comfortable fun. Just last week at a memorial for a dead friend, several of his long-time friends were asked to speak and one or two of them announced they were looking forward to the future time when they would join Ralph in a heavenly combo, playing jazz together once again in the presence of God. I have little doubt that God enjoys jazz, just as much as God enjoys Mahler, but the idea that we will all see one another again is in my mind a great cheapening of what rising to see God can possibly mean.

“O dwellers in the dust, awake and sing for joy” says Isaiah 26:19, in a Hebrew Bible hint of resurrection. But that hint is based squarely on the certainty of a God whose love and power can scarcely be imagined. That God is indeed “primal light” and to that light we will rise, being lifted with wings forged both by our fierce love in this world and by the unbreakable love that God has offered to us. I am grateful to Mahler, not only for his superb music in his symphony #2, but also in his gift of suggestive poetry that has helped me to think afresh about the idea of resurrection, one that has long troubled me, but one that I find important for my own life of faith and for the ultimate fate of all humanity. Whatever resurrection may mean, it assumes a God who rules over all things, and it assumes that our role in this life is to live with a “fierce love” that that God continually makes possible among us.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)