A significant challenge of the Narrative Lectionary is to decide just what portions of the rather long pericopes to discuss as one approaches the tasks of preaching and teaching. The goal of this list of texts is to provide a clear sense of the narrative movements represented in the chosen material. The Gospel of Mark is a parade example of a text that demonstrates obvious plotted movement, and lends itself beautifully to a narrative approach. Yet, it must be admitted that Mark’s subtle skills as narrative artist severely challenge the weekly preacher and teacher to communicate forcefully the carefully plotted structures that the writer offers. As I revealed earlier in my selection of the Narrative Lectionary to discuss in my weekly lectionary blog for this year, Mark was presented to me in my graduate study some 50 years ago to be a decidedly odd Gospel, sadly devoid of the great parables and monumental teaching language of the other three gospels. As I have learned in subsequent study of Mark’s work, my first teachers were not fully cognizant of what they were reading when they assessed Mark’s Gospel. After serious engagement with Mark by scholars with narrative interests and skills, Mark’s great work can be evaluated more fairly and may be seen to be an astonishing and scintillating piece of art.

A significant challenge of the Narrative Lectionary is to decide just what portions of the rather long pericopes to discuss as one approaches the tasks of preaching and teaching. The goal of this list of texts is to provide a clear sense of the narrative movements represented in the chosen material. The Gospel of Mark is a parade example of a text that demonstrates obvious plotted movement, and lends itself beautifully to a narrative approach. Yet, it must be admitted that Mark’s subtle skills as narrative artist severely challenge the weekly preacher and teacher to communicate forcefully the carefully plotted structures that the writer offers. As I revealed earlier in my selection of the Narrative Lectionary to discuss in my weekly lectionary blog for this year, Mark was presented to me in my graduate study some 50 years ago to be a decidedly odd Gospel, sadly devoid of the great parables and monumental teaching language of the other three gospels. As I have learned in subsequent study of Mark’s work, my first teachers were not fully cognizant of what they were reading when they assessed Mark’s Gospel. After serious engagement with Mark by scholars with narrative interests and skills, Mark’s great work can be evaluated more fairly and may be seen to be an astonishing and scintillating piece of art.

Mark 2:1-22 pushes the plot along in its headlong dash toward the crisis of the story that will not be fully revealed until the very end of the Gospel. For now, at the very beginning of Jesus’s public ministry, the basic difficulty of that ministry is that crowds are mobbing about this new preacher, demanding acts of power to solve the short-term weaknesses of body and mind that a miracle-worker is expected to perform. Jesus has made it quite clear that deeds of power are not the primary work he has come to do; rather he has come to preach a specific announcement that is summarized in Mark 1:15, namely that God’s time has now arrived, God’s rule in life is close enough to see and grasp, repentance is demanded now, along with belief in the good news of God as pronounced by God’s chosen one, Jesus. But human beings in this Gospel, unlike the demons, are confused about just who Jesus is, and instead of listening to his words, are eager to receive deeds of healing and wonder from one they see as the latest exemplar of power from some place of magic.

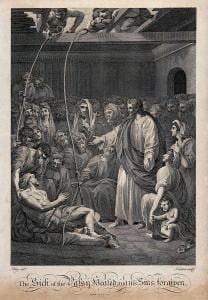

Mark 2:1-12 is a stunning example of human confusion in the face of Jesus’s central desire to preach the good news of God. In Mark 1:35 Jesus’s attempt to be alone for a time of prayer is soon interrupted by his eager disciples who urge him to get off his knees and get back to doing what everyone wants from him; healing. Instead, Jesus undertakes a preaching tour throughout Galilee, “so that I may proclaim the message there also, for that is what I came out to do” (Mark 1:38). So he “proclaims the message in their synagogues” (Mark 1:39), and along the way “casts out demons.” After a healing of a leper, accompanied by a stern warning not to tell anyone about the healing—a demand that is hardly likely to be followed!—Jesus returns to Capernaum, where “it was reported that he was at home” (Mark 2:1). But if Jesus imagines that he will finally get a bit of R&R, he is sadly mistaken. And if he supposes that the vast crowds that immediately surround his house are eager for a sermon on the good news, he is to the contrary confronted by a mob, demanding what the mob will always demand, namely deeds of power. “So many gathered around that there was no longer room for them, not even in front of the door; and he was speaking the word to them” (Mark 2:2). Well, he may have been speaking to them, but there is little indication that anyone was actually listening. What occurred around that Capernaum house was nothing less than chaos! There was no room anywhere close to the house, and one can only assume that Jesus’s attempts to speak his good news was drowned out by loud voices shouting for the next miracle of healing. In fact, things became so boisterous and out of control that four men, carrying a paralyzed friend for healing, gave up trying to get to Jesus while he was standing and speaking near the front door of the house, and resorted to climbing onto the roof of the house in the attempt to get their friend somehow into Jesus’s orbit of healing power.

What they do next has been the subject of considerable speculation. The text appears to say the following: “they removed the roof above him (Jesus?); and after having dug through it, they let down the mat (mattress or bed) on which the paralytic lay” (Mark 2:4). What this apparently means is that the four men first gain access to the flat roof of the house either by climbing the outside stairs to the roof, a common feature of houses of the time, or they make the house accessible by “removing” the walls of mud brick or limestone in such a way that it becomes easier for them to carry their friend into the presence of Jesus, who has apparently retreated into the recesses of the house. Whether they lower him from the roof, the usual understanding of the scene, or merely push him through the removed walls of the house, is less important than the fact that they lay the paralytic at the feet of Jesus, expecting him to cure the man.

What Jesus does do at first seems peculiar; Mark writes carefully, “When Jesus saw their faith (that is, the faith of the four men), he said to the paralytic, ‘Son, your sins are forgiven’” (Mark 2:5). Because the four men have trusted in the power of Jesus, he pronounces that the sins of the paralyzed man have been forgiven. That is a dangerous and astonishing claim in the context of 1st century Judaism. The passive verb form—“are forgiven”—implies that God is the agent. But in this context, anyone with a disease would have been viewed as one suffering the consequences of sin. As a result of that belief, a full repentance would be necessary before someone could pray for forgiveness and hope for healing. But what has occurred here is quite different: Jesus announces forgiveness without any indication that the paralytic has said or done anything “religious” at all. That leads directly to the umbrage of the assembled scribes of the Mosaic code who “questioned in their hearts” (that is, to themselves, not aloud), ‘Why does this fellow talk like this? It is blasphemy! Who can forgive sins but God alone?’” (Mark 2:6-7). Either the scribes are confused about what Jesus has done—has he forgiven the sin of the paralytic or has he, by using the passive verb form, said that God has forgiven him?—or do they less directly imply that the proper religious interactions have not occurred here— the paralytic has not repented and Jesus has thus announced forgiveness without repentance. In either case, they claim blasphemy, and become the first clear antagonists of Jesus’s ministry. They will hardly be the last.

Jesus closes the scene by confronting the scribes concerning what he has just done. Jesus asks here—note how carefully Mark writes—whether it is easier to say a word of forgiveness or a word of healing. This question puts the scribes in a bind; if they say it is easier to say, “Get up and walk,” they will imply that Jesus has already done the more difficult thing, namely forgiven sins. But if they say that forgiving sin is the easier act, when Jesus then performs the act of healing, they will need to admit that he is able to do the more difficult thing, rendering false their claim that he has done something blasphemous. In short, Jesus outwits his enemies, something he will do again and again in the ensuing tale. Jesus proceeds to heal the paralytic, who immediately “takes his mat and went out before them all” (Mark 2:12). “And they were all amazed and glorified God, saying, ‘We have never seen anything like this’” (Mark 2:12). That is a delightfully ambiguous phrase. What exactly is the “this” in the sentence? The healing? The duel with the scribes? The forgiveness of sins? The trust of the four men? All of the above? Perhaps the remainder of the Gospel will provide a more definitive reply to that question, but at this point, we, the readers, are most anxious to receive a reply, since that is why we are reading Mark’s work in the first place: just who is Jesus and what more precisely is it has he come to do? The tale rushes on, and we are increasingly concerned to discover Mark’s answers to those questions. Stay tuned!