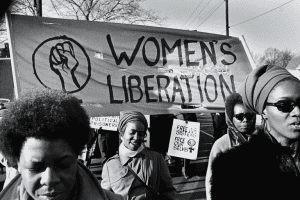

I finished my college education in 1968, having been schooled during the “turbulent 60’s,” a time of radical and uprooting changes in the world. The Vietnam war was raging, many of us young men were facing the distinct possibility of being drafted for that war, a war many of us felt was horrifying, needlessly destructive both of American and Vietnamese lives, being fought on false pretenses. When the lies of the events surrounding the incident in the Tonkin Gulf became known, we turned out to be right. In addition to the monstrous war, there were the opening glimmers of the women’s movement, the new found freedoms of sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll, significant changes in fashion from Nehru jackets (yes, I had one) to ever-shorter mini-skirts (yes, my wife of 50+ years had a few of those).

I finished my college education in 1968, having been schooled during the “turbulent 60’s,” a time of radical and uprooting changes in the world. The Vietnam war was raging, many of us young men were facing the distinct possibility of being drafted for that war, a war many of us felt was horrifying, needlessly destructive both of American and Vietnamese lives, being fought on false pretenses. When the lies of the events surrounding the incident in the Tonkin Gulf became known, we turned out to be right. In addition to the monstrous war, there were the opening glimmers of the women’s movement, the new found freedoms of sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll, significant changes in fashion from Nehru jackets (yes, I had one) to ever-shorter mini-skirts (yes, my wife of 50+ years had a few of those).

And in the midst of all of that, something much more important was happening, especially among those privileged few of us, attending elite colleges during those days. We began to question the authorities that had guided our lives and the lives of our parents and grandparents for as long as we could remember. Men were strong, and always needed to be the “breadwinner” of the family, we had assumed, a family that included husband, wife, and 2.5 children. The wife stayed home with those children, while her husband went to work. It became clear to us that that paradigm was no longer the norm for many. Women worked outside the home in increasing numbers (my own mother worked as a nurse during all of my years at home), and men, albeit often quite reluctantly, took their places as homemakers, childcare givers, cooks, and washers of dishes and clothes (my father unfortunately did none of those things). Those were obvious cultural shifts, but there were other alterations in the basic transfer of knowledge that we experienced in our college classrooms, changes that had equally significant long-term effects on our society, though those effects were far subtler.

The so-called “canon of the Western world,” those books, paintings, pieces of music that had served as the bedrock of what we called civilization, fell under increasing threat, and began to be seen as hegemonic, as destroyers of various voices that had been silenced by their assumption of power. Where were the “Negro” (now African-American) authors and artists, and why were we not studying them? Or the Latinos? Or the women? And with the slow recognition that not all of us were in fact heterosexual, where were the queer artists, the word “queer” now being used quite positively, rather than as a put-down for LGBTQIA people? In short, the entire, supposedly settled notion of “authority” was under siege, and those of us who were listening to these struggles, and who were at least partially sensitive to the earthquakes rumbling beneath us, began, however dimly, to realize that “the times, they were a changin’.” From 1968 to the end of the 20th century change accelerated at rocket speed; my days as university professor witnessed all of this rapid evolution of society.

However, one result of this questioning of authority, was deleterious. If “your” authority was no better than “my” authority, or if authority could be selected not on the basis of argument and reason, but on feeling and personal opinion, then knowledge itself was no longer a generally accepted fund of rational information, but became instead an individual decision, the result of choice. In time, there was no way we could talk reasonably with one another, since “your” knowledge was in effect not the same as “my” knowledge; you and I look at the same information, the same events, and see in them completely different understandings of what they mean, of what their significance is for us. It all came down to whom we listen to; just who are the purveyors of expertise among us? Or, most radically, are there finally any true experts who know more than I do? After all, I have access to the Internet, that universal fountain of infinite knowledge, just as the so-called experts do. Why should what they know be any better than what I know?

Soon, central societal institutions were attacked as out of touch with many of these changes. The lies of Vietnam, from generals to presidents, forced us to ask serious questions about those heretofore accepted authorities. The depredations of Richard Nixon led to his resignation as president, a fact that compounded the distrust of politicians and the uncertainty that any of them could be trusted at all. From Reagan to Trump, they are all the same, spreaders of their own truths, some of which I agree with, some of which I don’t. Their authority is at best provisional, at worst no authority at all.

And now in the midst of COVID-19, the worst natural disaster the world has faced in 100 years, our television screens are full of experts, epidemiologists and formidable doctors, who in studied tones and armed with charts and facts, warn us and urge us to follow their directions if we are to weather this microbial storm. However, while these experts share their vast knowledge with us, hogging screen time are a stream of mental pygmies who claim knowledge, but who urge dangerous and unproven “cures” on us, who tell us that we may need to sacrifice some thousands of our citizens in order to open up our devastated economies again, who send tweet storms against those who cannot agree with their dicta about the virus, and their blustering and stuttering attempts to curb its shattering effects on all of our lives. Unfortunately, the past 50 years have taught too many of us that expertise is not to be trusted, that feelings are all that matter, that my rights to freedom are more important than the lives of a few unproductive and creaky members of my country. So, they shout, “Open my country, and those who cannot survive are perhaps not worthy of survival at all.”

Our overt and persistent questioning of the power of expertise over the past half century has led us all to this place, a dangerous and potentially disastrous juncture in American history. Please do not misunderstand what I am trying to say; it was inevitable that the unrelenting questioning of every nostrum that we assumed was unquestionable would occur. We had, as thinking human beings, to call all of what we thought we knew was sure and certain into the sharpest question, and we certainly did that with a vengeance. Now, we reap the whirlwind of Donald J. Trump, the very epitome of a man unschooled in everything save marketing and sales, a complete narcissist, who turns all events into something about him, who can muster no empathy or sympathy for the millions of humans now infected, gravely ill, or dead of COVID-19, who rejects serious science, serious reading, serious reflection on larger issues of human life as uninteresting, useless, not important for the sale, not good for the market, not valuable for his reelection, his portrait of what will make America great.

I see these tragic events, bred by our own searching desires for wider knowledge and larger truths, in the light of that old story in Gen.3, that ancient tale of the Garden of Eden. It was inevitable that the first woman and the first man would eat from that tree of knowledge, for human beings were created to thirst for knowledge. The snake promised the woman that they would be upon their eating “like gods,” or even “exactly God” in another possible hearing of the text, but the result of their fruit lunch was not divine knowledge, but instead the need to solve their newly discovered problem of nudity with fig-leaf aprons. All ancient hearers of the story knew all too well just what fig-leaves feel like, and knew immediately how long any fool would wear such a thing close to their nude flesh—in short, not very long! And there we are! Our grasping at vast knowledge, unaccompanied by any checks at all, our unstoppable attempts to know all things without listening to those who have thought through some of these things and who have careful advice and sound warnings to provide, have led us to our own fig-leaf aprons, our own half-baked bits of information, our ridiculous claims of conspiracy and cabal, our constant and loud proclamations that we are right, and they are wrong. Listen to me, they cry, not to those who actually may know something, who may have experience that is crucial, who may speak a truth that I need to hear, who are ready and anxious to share what they know with those willing to pay attention long enough to recognize that they do not and cannot know all that is needed in every situation.

We are still scratching ourselves in our fig-leaf aprons, imagining that we are god- like, projecting ourselves as the smartest ones in the room. We desperately need a rebirth of expertise in these days, and we desperately need the silence of those mountebanks who claim more knowledge than they obviously have. I accept my responsibility as one of those elite educated ones who drove us all to question everything and everyone, leaving us without open ears for those who really do know things. May you find experts, and then may you listen to them. I try hard each day to search them out and act accordingly so that I may at last shed my fig-leaf apron and live with all the world’s citizens in peace and future joy.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)