In my last essay, I attempted to read a text from the Bible through the lens of the exploding conversation on race that the murder of George Floyd, among too many other documented deaths of African-American citizens at the hands of police, has generated in our time. Though violent protests have receded in our cities, large crowds continue to form, legislation has been proposed in the Congress aimed at addressing the crisis of racism, both among the police but also in the society in general, and serious voices have been raised with multiple suggestions to take on this long-simmering problem in America. It seems far past time to hear the scriptural text in the light of this immediate question. I know full well that biblical scholars, especially over the past 20 years or so, have included an African-American racial context in their readings, along with any number of other contexts: LGBTQ, Latino/a, issues surrounding empire, including economic, political, and social contexts. My goal in that earlier essay, and in this one, is to read with my white eyes a text, attempting to hear the voice of the oppressed, with a special concern for the questions the massive protests in recent days have made all too important and all too central for our thinking as a struggling country. I am sure that I will demonstrate my white privilege in my reading, as I have regularly done over my 50 years of serious engagement with the Bible, but I also hope that I will begin to see at least in part what my black brothers and sisters are trying to tell me in order that I might begin first to listen to what they are saying and then speak with them in their pain and fear as they confront a racist society of which I am part and from which I profit.

In my last essay, I attempted to read a text from the Bible through the lens of the exploding conversation on race that the murder of George Floyd, among too many other documented deaths of African-American citizens at the hands of police, has generated in our time. Though violent protests have receded in our cities, large crowds continue to form, legislation has been proposed in the Congress aimed at addressing the crisis of racism, both among the police but also in the society in general, and serious voices have been raised with multiple suggestions to take on this long-simmering problem in America. It seems far past time to hear the scriptural text in the light of this immediate question. I know full well that biblical scholars, especially over the past 20 years or so, have included an African-American racial context in their readings, along with any number of other contexts: LGBTQ, Latino/a, issues surrounding empire, including economic, political, and social contexts. My goal in that earlier essay, and in this one, is to read with my white eyes a text, attempting to hear the voice of the oppressed, with a special concern for the questions the massive protests in recent days have made all too important and all too central for our thinking as a struggling country. I am sure that I will demonstrate my white privilege in my reading, as I have regularly done over my 50 years of serious engagement with the Bible, but I also hope that I will begin to see at least in part what my black brothers and sisters are trying to tell me in order that I might begin first to listen to what they are saying and then speak with them in their pain and fear as they confront a racist society of which I am part and from which I profit.

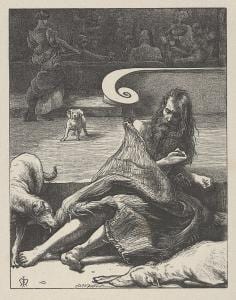

Today’s text has long been one of my favorite parables from the Gospel of Luke, the story of the rich man and Lazarus. Some have argued that it is not a parable at all, but a warning story about the rewards of heaven and the punishments of Hell. I find its interests and focus elsewhere, as I will try to demonstrate. The tale is found in Luke 16:19-31. The immediate context of the story is a sort of hodge-podge of Lukan material, including the much-discussed Parable of the Dishonest Manager (16:1-9), followed by a series of reflections on various subjects (16:10-13), leading to another confrontation with some Pharisees, “who loved money,” who ridicule Jesus for his comments about money, apparently reacting against a certain reading of the dishonest manager story, along with his use of “dishonest wealth” (16:11) as an example of poor faithfulness. There is even a one-verse condemnation of divorce that immediately precedes our story (16:18). I find the context not immediately helpful in the attempt to grasp what this story is saying; the story must be read on its own as a remarkable look at oppressors and the oppressed.

“There was a rich man (dives in Latin, meaning “rich man,” causing some to name the man) who was dressed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day.” Quickly, the story portrays a man of power and wealth, dressed in purple, a color only produced from tiny Mediterranean mollusks that require dangerous harvesting and lengthy transport and processing only a very rich person could afford. In addition, his clothes are “fine linen,” again cloth produced with special care, woven from the finest material, shimmering and thin. And his meals every day are nothing less than sumptuous feasts, from tables heavy laden, capped off with the very best wines from the world’s vineyards. Here is the very definition of wealth in 1st century society.

By way of stark contrast, a man named Lazarus (“God helps” in a shortened Hebrew) is poor, lying at the gates of the rich man, covered with sores, longing to satisfy his gnawing hunger with the most wretched of left-overs, whatever fell off the rich man’s table, whatever his pack of hungry dogs failed to snatch up. Those very dogs came to lick his sores, Lazarus being too weak to shoo them away. The fact that Lazarus is named while the rich man is not, an important element of the story, I think, is unfortunately covered over when the name “Dives” is given to the rich man. Without a name, the rich man is generic, a representative of a class of powerful wealthy people, but Lazarus is a person, overlooked and forgotten by the rich.

Both men finally die, as all persons do, but their fates are quite different. Lazarus is “carried by angels to be with Abraham,” the patriarch of Israel, while the rich man is buried, as are all who die, but finds himself in Hades in torment. In the literature of the 1stcentury CE, Hades, the Greek god of the underworld, was regularly the Greek translation of the Hebrew sheol, an underground place of darkness and gloom where all lead lives of unenviable, fading existence. But soon attempts to speculate on the details of life after death led to ideas of torment and punishment. In this story, Hades has become such a place. Now the power of the story begins to be revealed.

The rich man “looked up” and saw Lazarus, that wretched impoverished sore- ridden man who had sullied his mansion’s gate, now resting comfortably with the great Abraham. He does not address Lazarus, but Abraham whom he obviously assumes can help him; he sees Abraham as one on the same societal rung as the rich man has always been. Lazarus, he assumes, cannot help him, because he is poor and has no need of speaking to him or listening to him. “Father Abraham,” he cries, “have mercy on me; send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue, because I am in agony in these flames” (Luke 16:24)! Note that the rich man sees Lazarus still as merely a servant who does the bidding of his betters; send him down here to help me, he demands. The rich man has learned nothing in his dying and torment.

“Too bad,” answers Abraham, to the rich man’s request. You had all those lovely things while you were alive, all that purple linen, all that fine food, all that power and wealth. Lazarus, however, had nothing. Perhaps the implication of Abraham’s address is that the rich man could have seen Lazarus if he had looked at him lying at his gate and heard his hungry cries, but he did not. He has comfort now, while you have only agony. And now there is a great chasm fixed between the two of you, unlike the separation between you two in life, a separation that you, rich man, could have bridged, if you had seen, if you had listened. In desperation, the rich man “begs Abraham to send him to my father’s house” (the rich man just cannot stop seeing Lazarus as a servant!). I have five brothers, he cries. Let Lazarus warn them, “so that they do not end up in this place of torment” (Luke 16:28).

“Nothing doing,” replies Abraham. “They (your brothers) have Moses and the prophets (i.e. the Bible!); they should listen to them” (Luke 16:29). “No, father Abraham, if someone goes to them from the dead, they will turn around” (Luke 16:30)! I doubt it, says Abraham. “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead” (Luke 16:31)! I have long found that final sentence to be one of the most important ones in the New Testament. If we do not hear Moses and the prophets, we will certainly not be changed at all even if someone rises from the dead. Since the entire New Testament gospel is based squarely on the conviction that Jesus rose from the dead, however one may understand that, it is telling that Abraham warns the rich man that listening to Moses and the prophets, namely the Torah of the Hebrew Bible, is crucial if one is to be able to listen to Lazarus, the poor man in our midst. For what else do Moses and the prophets say but pay careful attention to the poor, to the widow, to the foreigner, to those on the margins, to the Lazarus lying at your gate. Moses and the prophets bid us listen to Lazarus; if we do not, then any resurrection of Jesus will finally be meaningless to us, a doctrine devoid of meaning or use.

I suggest that the cries of African-Americans at this moment in our history are the cries of Lazarus, lying at our gates. For too long we white and privileged ones have closed our ears to those cries. And especially we white and privileged readers of the Bible have not finally heard the essence of Moses and the prophets, the call for us to listen especially to the cries of Lazarus, who calls out for justice, for food, for equal access to the goods and services of 21st century America, who asks for us to walk with him, not to treat him as servant, either to tell us what to do or what to read or how to act. But instead who calls us to walk alongside him, seeing him and listening to him at that gate of affliction, that place of pain, to stand up for him and with him as all of us move toward a better world, a world of unity and hope for all of God’s children.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)