I have spent well over 50 years of my life as a student and teacher of the Bible. It has often been jokingly said that the Bible is the most bought, least read book in the history of publication. That may be true, but its pages have had an outsized influence on culture over the two millennia of its publication, now in hundreds of languages, across hundreds of cultures. What I want to try to do in what may finally be three essays is to trace the rise of the Bible as it grew into the book it became, then examine the various ways it has been read and heard over the centuries of its use, and lastly to explore its modern employment in our world now. Obviously, three brief essays will hardly exhaust such a rich subject, but I want to look at the book from a macro level, that is see the forest that is often choked by the trees of its many quotable texts. This first essay will examine how the Bible became the Bible from its origins in ancient Near Eastern culture to its canonical status in the 4th century CE. Please note my title: this is an imaginative sketch necessarily because there is a paucity of historical verification, along with a huge disparity between historical reconstructions of the Bible’s growth; but a lack of information seldom stops scholarly speculation, and it surely will not impede my analysis, however fanciful some may find it.

The starting point must be located in and around the tents and campfires of tiny groups of shepherds and farmers, late in the 2nd millennium BCE, as they gathered to share the stories of what they had been told that their God had done for them to bring them to their precarious places of life on the rocky hillsides and deep ravines of what became central Palestine. Those tales included, most centrally, the conviction that YHWH, the mysterious and potent deity of their ancestors, had magically defeated the Egyptians, the world’s most powerful peoples, through the agency of a man named Moses, who by signs and wonders demonstrated that YHWH, not pharaoh, was master of the earth. Not only did they share the stories, but they also celebrated them with poems of praise, some borrowed from the Canaanites who lived around and among them (Ps.29), and others created by their own bards. These stories and poems were kept alive by word of mouth, through continuous repetition, through the coming ages. It is unlikely that many were written down in this early period, writing being both rare and expensive.

As the peoples of the hill country grew and expanded, their initial larger communities first relied on a governmental structure that awaited the next miraculously chosen figure from their God—the Judges—a structure that was eventually found inadequate to maintain stability and to withstand the constant assaults and threats of the enormous empires that surrounded them both east and west. They turned to kings to govern them, and with the rise of kings came the rise of prophets to call the actions of those kings into question. At first, prophets like Nathan, Elijah, and Elisha were merely written about well after the time of their speaking, but by the 8th century BCE prophets, or their disciples, began to write down some of their oracles, out of which collections were compiled and circulated in some written forms. Thus, we can read of Amos, Isaiah, Micah, and Hosea, followed in the next century by Jeremiah and Ezekiel. From perhaps the 8th to the 6th centuries prophetic material was available for reading by the few and for hearing by many more as counterweights to the actions of the kings who, with few exceptions, were found to be inimical to the community.

During this same time, the great tales first told around the fires were finding a more definitive codification, as the nation continued its struggle for survival and for stability as a people. In addition, those early psalms became the core of a growing number of poems that were used in worship in small shrines and finally in the 10thcentury temple in Jerusalem. Also, we know that late in the 7th century, King Josiah, remembered by some as a reformer, discovered in the walls of the rebuilding temple a scroll of something like the book of Deuteronomy, in 622-621BCE to be more exact. Here is evidence of a written text, and after the prophet Huldah determined that this text is from YHWH and must be followed to the letter, Josiah begins a great cleansing of Israelite worship and practice in response to its demands. Thus, by late in the 7th century, there were certain written documents that became part of the Bible we know.

But the event that brought about the huge increase of Israelite writing occurred in the 6th century, both in 597 and in 587 BCE, when Jerusalem was sacked by the Babylonians, and the leaders of the nation of Judah, the king, the court, and the intelligentsia of the community were carted off to Babylon into exile for the next 50 years. It was there in Babylon that the outlines of the Bible were shaped. This is so because with the central promises of YHWH to Israel all now called into serious question—land, king, priest, temple—the exiled people had to find a source of stability and hope of a different sort, and they found both in the assembly of a sacred book, or more accurately a series of sacred documents from which they could lay a foundation for a new future, either in exile or after their return to their homeland. In exile, surely the Torah, the central first five books of what became our Bible, found its shape, as did the bulk of the prophetic writings. Of course, II and III-Isaiah were written in the exile itself or soon after, as is made clear in those texts. Job may have been composed then, too, in response to a too-easy conviction of the place of YHWH in the nation’s life, as presented by II-Isaiah. The tensions of a boiling theological cauldron in exile surely forced hard thinking about any future for these people.

After the return from exile as the gift of Cyrus, King of Persia, in 539BCE, the people brought with them portions of the written texts that continued to serve as the basis of a renewed people. It was a difficult struggle to rebuild the temple and to restart the Judean community, and for perhaps 100 years after the return Jerusalem and any semblance of a nation was not a fixed reality but remained little more than an apparently vain hope. However, with the coming of the scribe Ezra into a somewhat restored city in the middle of the 5th century BCE, a new power for the text emerged. (Admittedly, there is enormous scholarly disagreement about the work and the timing of both Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s coming to Jerusalem). But if the great scene described in Nehemiah 8 has any historical root, then this pious Jew brings with him to the city something like a Bible, at least a Torah, and reads to the assembled people from it at the reconstructed Watergate of the city. Because he reads apparently in Hebrew, the sacred tongue, many that day may not have been able to understand it since most by this time were Aramaic speakers. Thus, we hear, perhaps for the first time in our Bible’s history, the necessity of interpretation, both linguistic and meaningful elucidation, in order to grasp what the sacred text may mean for a new day (Neh.8:8). That scene will be a model for the millions of attempts over the next 2500 years for people to make sense of the ancient text for their own time.

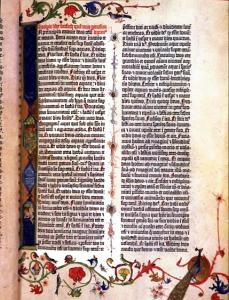

The sacred text remained valuable as a guide and stay over the next troubled life of Israel, as the people were first overwhelmed by the Greeks and then the Romans, with language requirements shifting from Greek to Latin, always filtered through the west Semitic dialects of Hebrew and Aramaic. By necessity, the texts, if they were to retain their power, had to be translated into the reigning languages, from Greek and the Septuagint translation, to a Syriac translation (an Aramaic dialect) and finally to the Latin of Jerome, the Vulgate that became the favored translation for the Roman Church until the early 20th century. During the final centuries of the world before the coming of Jesus, the several latest books of the Hebrew Bible were composed from Koheleth perhaps in the 4th century BCE to Daniel in the middle of the 2nd century BCE.

When the Romans sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE, destroying the temple of Herod and forcing many Jews to flee the city, a myth developed that a group of rabbis met in the city of Jamnia and closed the canon of Jewish scripture. Such a thing never happened. The so-called canon of the Bible remained fluid for several centuries after the fall of Jerusalem. Indeed, books were included in the emerging list of sacred texts as they were found useful to various groups of believers, while others were discarded for the same reason. With the rise of Christianity, and its early creation of texts, from the letters of Paul, that circulated quite early, perhaps by the mid-60’s in the 1st century in the emerging Christian communities of the Mediterranean basin, to the four gospels, written from 70 to 90CE, to the book of Revelation, usually thought to have been composed in the middle of the 10th decade of the first century, as well as the later pseudo-Pauline letters, bringing us to the beginning of the 2nd century, the 27 books of the New Testament found a place in the sacred canon of New Testament scripture. However, that canon (a word meaning “measuring stick”) was not really closed, if even then, until a letter by Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria was written to the churches of his area in 367CE, listing the 27 books of the New Testament we know. But it should be noted that even then, the canon remained somewhat flexible. For example, the Syrian Christian church to this day does not have Revelation in its canon. And of course the modern Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints has included several books in its canon that other Christian churches do not recognize, namely the Book of Mormon.

That is an absurdly brief sketch of a very complex story. In the next essay I will explore the various ways that the Bible has been read through the nearly two millennia of its existence, an equally rich and complex tale.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)