The story of the rise and fall of David is a very long one, and the compilers of the lectionary had to make choices concerning which parts of the tale they would highlight. Between the foul actions of the king and his upbraiding by YHWH through the prophet Nathan (2 Sam.11-12), there lies the story of David’s son, Absalom, and his attempt to usurp his father’s throne. That painful narrative involves the portrayal of an arrogant and narcissistic boy, enamored with power, in love with his luxuriant hair, overly fond of public displays of grandeur, and particularly consumed with a passion for fine chariots and dare devil speeds. The upshot of these massive public spectacles is that Absalom is finally successful; David is tossed out of Jerusalem and the grandiose son is ensconced on the throne of Israel. Most especially, Absalom has stolen the throne because he has “stolen the hearts” of the people in the absence of his father’s waning concern for his central role as king of Israel (2 Samuel 15:6).

The story of the rise and fall of David is a very long one, and the compilers of the lectionary had to make choices concerning which parts of the tale they would highlight. Between the foul actions of the king and his upbraiding by YHWH through the prophet Nathan (2 Sam.11-12), there lies the story of David’s son, Absalom, and his attempt to usurp his father’s throne. That painful narrative involves the portrayal of an arrogant and narcissistic boy, enamored with power, in love with his luxuriant hair, overly fond of public displays of grandeur, and particularly consumed with a passion for fine chariots and dare devil speeds. The upshot of these massive public spectacles is that Absalom is finally successful; David is tossed out of Jerusalem and the grandiose son is ensconced on the throne of Israel. Most especially, Absalom has stolen the throne because he has “stolen the hearts” of the people in the absence of his father’s waning concern for his central role as king of Israel (2 Samuel 15:6).

While David is running for his life from his traitorous boy, that boy is attempting to determine how he should consolidate his power over Israel. Two of David’s former counselors, Hushai and Ahitophel remain in Jerusalem to provide advice for the new king. The former has in fact been planted by David as a counter weight to the counsel of Ahitophel, whom David knows will offer sage advice to the fledging monarch. Absalom calls both to the throne room, anxious to decide what to do with the fleeing David. Ahitophel counsels immediate attack, knowing well that if David is given too much time he will find ways to consolidate his scattered forces and will gather a formidable and veteran army, one that will destroy the inexperienced forces of Absalom. But Hushai, rushing to contradict the advice of Ahitophel, urges Absalom to delay an attack against David, saying that the former king will be “like a bear in the field bereaved of its young” (2 Sam.17:8), too dangerous and furious to stir up too soon. Hushai demands that Absalom delay his assault against his father for a more propitious time. Disastrously, Absalom listens to Hushai rather than to Ahitophel. The latter, knowing the wiles of David far better than Absalom, “saddled his donkey, arose, and went to his home to his town, and leaving charge for his household, hanged himself and died” (2 Sam.17:23). And he was buried in the tomb of his father.

The delay of the attack against the fleeing king is a catastrophe for Absalom, as today’s text makes all too plain. This final story of Absalom’s life begins with a telling scene. Now that King David has been given the time to refresh his forces, he musters a significant group of fighters, and places his general Joab, Joab’s brother Abishai, and a foreign mercenary, Ittai, each over a third of the army. These are seasoned warriors, against whom the armies of Absalom are at a serious disadvantage. David stands in front of this army and declares, “I will go out with you,” proclaiming proudly that, as in times past, the king himself will front the troops (2 Sam.18:2). However, we have read nothing of David’s personal battle leadership since that fateful day in Jerusalem when the king “remained in Jerusalem” despite his entire army heading to Amman for battle (2 Sam.11:1). He has been, as far as the story relates it, a sedentary king, not a commander of armies. Hence, his soldiers, knowing all too well that David’s battle days have passed, urge the king to stay in the town, saying with obvious flattery that “you are like ten thousand of us,” inferring that his loss would be a catastrophe for Israel. “Whatever is good in your eyes I shall do,” David replies meekly, indicating perhaps that he knows his fighting days have ended.

However, as the troops are heading out to confront the army of Absalom, the king has stern and clear words for the three leaders: “Deal gently for me with the lad Absalom” (2 Sam.18:5). The translation “deal gently” is that of the KJV, and has become a near cliche, retained by numerous subsequent readings. The verb here is quite rare, from a root meaning “cover,” hence the meaning may be “protect,” a synonym of the verb employed at 2 Sam.18:12 when a soldier, refusing to murder Absalom, shouts to Joab that he would never kill the helpless Absalom, given the demand that King David uttered about “watching over” him.

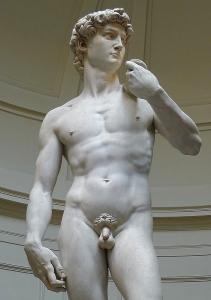

The battle is joined near a huge and dense forest (such forests covered much of the land nearly three millennia ago), and the story teller says that “the forest devoured more of the troops than the sword devoured on that day,” suggesting that the raw recruits of Absalom’s army may have retreated headlong and heedlessly into the tangled trees, perhaps slashing out in panic and killing even those of their own forces. Even the power of nature appeared to be against Absalom. The new king himself, fleeing from the lost battle, steers his mule (the animal always used then for transport—horses were employed much later in battle) into the thicket, but both pathetically and hilariously, becomes snarled in the branches of a tree, ensnared by his glorious mane of hair, while the terrified mule continues on, leaving Absalom to “dangle” in the air (the best Hebrew texts here read “he was given,” but numerous ancient translations from Aramaic to Latin, including now the Qumran Samuel scroll read “dangled,” only one consonant different from the Hebrew text).

A soldier from David’s army spies the helpless Absalom, swinging and spinning by his hair, and rushes to report the sight to general Joab. Upon hearing of the young boy’s plight, the cruel Joab upbraids the soldier, telling him that if he had murdered the would-be monarch, “I would have given you ten pieces of silver and a belt” (2 Sam.18:11). Not on your life, shouts the soldier! “Even If I were to carry in my palms a thousand silver pieces, I would not reach out my hand against the king’s son.” He has heard the king’s charge about protecting Absalom, and knows that anyone who dares do such a thing would face the king’s fury. All know well what David has done over the years to those who cross him; death is often their reward. But Joab, despite the words of his king, knows well what must happen to traitors, especially if they are heirs to the king’s throne. They must die without fail, but Joab too fears the wrath of David so devises a way to spread the guilt for Absalom’s death around. He “thrust three sticks into Absalom’s chest, still alive in the middle of the tree” (2 Sam.18:14). He does not, as many translations claim, thrust three “darts” into the boy’s chests, a surely fatal act. The “sticks” are designed to stun the heir in order that “ten lads, Joab’s armor bearers” might surround the helpless man and dispatch him instantly with a furious and brutal assault. They then pull his lifeless corpse out of the tree, toss it into a very shallow grave, and heap a random pile of stones on top of it. It is a completely ignominious end for a would-be king. Notice how Absalom’a death compares with that of his counselor, Ahitophel. Both ride a mule, both hang from a tree, and both are buried. But in Ahitophel’s case, his self-hanging leads to a burial in the family vault, but for Absalom there will be no state funeral, but only a forgotten pile of rocks in the wilderness.

And now David must be told of the success of the battle. A son of the priest Zadok, Ahimaaz, requests from Joab the right to bring the news to David. But Joab remembers well what David has done with messengers who bring to him bad news—in this case the death of his son against his strict orders—; the Amalekite who brought news of Saul’s death, the two men who murdered Saul’s tragic son, Ishbosheth all became victims of David’s anger. Joab thus denies Ahimaaz the duty to tell the news of the battle, but sends a foreigner instead, a Cushite. Still Ahimaaz is determined to be the bearer of the news and runs faster than the Cushite, arriving back to the city where David waits for a report. It becomes immediately apparent that all David cares about is the fate of his son. When he asks Ahimaaz that direct question, the man hems and haws, uttering half-sentences and garbled prose in reply (2 Sam.18:28-29). But when the Cushite appears, he replies with boldness: “May the enemies of my lord the king be like the lad, and all who have risen against you for evil” (2 Sam.18:32)!

David’s response to this news is famous and wrenching. “My son, Absalom! My son, my son, Absalom! Would that I had died instead of you! Absalom, my son, my son! And the victory on that day turned into mourning..” (2 Sam.19:1-3). This wailed response of David is a far cry from the other occasions when the king has faced deaths of those close to him. When Saul and Jonathan met their ends on Mt. Gilboa, David’s response was a superb elegy, as much political as personal. When the general of Saul’s army, Abner, was cruelly murdered by general Joab, again David turned to poetry, a poem designed to dissociate himself from the killing, laying the blame solely on Joab. When Bathsheba’s infant son died, the fruit of David’s adultery, he was led to quiet words about his own morality and the inevitability of death. Now all that studied eloquence is gone; David now can only stammer out in grief. One would enjoy concluding that David is making some sort of personal growth in the face of these deaths, but in fact death will dog him until the very end of his life when even as he is dying, he feels the need of colluding with another son and heir, Solomon, in the revenge murder of an old and helpless enemy, Shemei, who decades before had humiliated the monarch as he fled from that other now dead son, Absalom (1 Kings 2:8-9).

What are we to make of this David? He is a deeply complex man, the portrayal of whom is among the very finest in all of ancient literature, who until the end of his life is beyond simple description and evaluation. He is both model of God’s choice and not model, a man of so many parts as to defy logic. In short, he is a man at full stretch, a human being who is all human, bad and good, dangerous and delightful, charismatic and monstrous. Is he not finally each of us, hyperbolically pictured to be sure, but our mirror, somewhat distorted perhaps, but an image of us nevertheless, an image not to be denied but embraced and observed as we are able? By all measure, David is a man impossible to avoid, impossible to deny, impossible to overlook.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)