I am now 73 years old, and never imagined that I could actually become that old. My father died at 73, though my mother lived until 92, while her two brothers died in their late 80’s, and my Dad’s mother lived until 97. I have long-lived folk in my family tree (my mother’s father died at 96), which, while not any sort of assurance, suggests that I may live quite a bit longer. No one wants to live past their decent health, especially beyond their mental acuity, but among the fastest growing societal groups are those who have topped 100. I cannot know when my end will come, but I can certainly envision that end from my 73-year old hill. I am obviously far closer to my end than my beginning.

I am now 73 years old, and never imagined that I could actually become that old. My father died at 73, though my mother lived until 92, while her two brothers died in their late 80’s, and my Dad’s mother lived until 97. I have long-lived folk in my family tree (my mother’s father died at 96), which, while not any sort of assurance, suggests that I may live quite a bit longer. No one wants to live past their decent health, especially beyond their mental acuity, but among the fastest growing societal groups are those who have topped 100. I cannot know when my end will come, but I can certainly envision that end from my 73-year old hill. I am obviously far closer to my end than my beginning.

I find the preceding factual discussion not maudlin or inappropriate in the least. Death is a given in life, and must be faced by all of us. The question for me today is exactly how my faith in God affects, or does not affect, my approach to my death. It may appear obvious that I, as an ordained United Methodist clergyman, should face death with faithful equanimity, if not a calm assurance that no matter what, God will be there. I admit that my calm or my equanimity is neither in constant supply. I have my fears, and I think those fears need to be voiced and faced.

Next week, I am scheduled for cataract surgery, first in my left eye and some two weeks later in my right. I knew this was coming; it is well nigh an inevitable result of aging. The surgery has become far less onerous than it once was, and the success rate is quite high. Because I have the beginnings of glaucoma, I cannot receive the multi-focal lens that some can, thus obviating the need for glasses. I may only do the mono-focal lens that should aid my distance sight, though I will still need glasses for other purposes. Because I have worn glasses for over 60 years, that is not a problem for me at all. In fact, my glasses have become so much a part of my life—first on in the morning and last off at night—I cannot envision (pardon!) a life without them. Still, the surgery itself is a sign of my place among the older members of the culture, since the great majority of those undergoing cataract surgery are my age or older.

I am afraid of the surgery. The description of the process, the shattering of the lens, the removal from the eye of the resulting pieces, and the len’s replacement by something artificial, fills me with dread. It is a brief procedure, and I fully trust the doctor who will do it, but I remain fearful. Things can go wrong, of course, and the thought of possible unexpected consequences does not aid my ease. I know full well that I need this surgery, but I am reluctant to do it.

Should not a faithful Christian be more sanguine about both surgery and aging? Is not the Bible rife with admonitions to “fear not,” from Moses at the Sea of Reeds to the angel chorus in the skies over Bethlehem? I know all too well these grand passages, having preached from many of them numerous times, times of national and personal fears. But now it is I who am the fearful one, and I am finding it surprisingly difficult to access the faith I have long proclaimed. Just how is one to grab onto the promises of God to be available and present on occasions of fear and foreboding?

My good acquaintance, Walter Breuggemann, a renowned teacher of the Hebrew Bible, and prodigious author of helpful words about things biblical, wrote a book some years ago with an arresting title: Finally Comes the Poet. I have long loved the main thrust of this book, since it proclaims that after all the reasoned and rational ideas that we may learn and access, that we may discuss and debate, at the last a poet shows up to tease us toward elements of ourselves that rational thought may not touch. He used the prophets primarily as examples of those who employed poetic language to confront their hearers with truths that move well beyond what their rational minds could understand. Exactly how does YHWH ask for justice, says Amos? Does he say, “Learn the Torah and apply it in your lives”? No! He says, “Let justice roll on like waters and righteousness like a perennial stream,” employing poetry of unmatchable and unforgettable power that resounds some 2700 years after first it was uttered.

When the apostle Paul confronted the awesome and dreadful reality of death, he did not proclaim that we needed to understand and accept the truth that God defeats death in divine power; he rather resorted to poetry when he announced to his Roman readers that “nothing can separate us from the love of God—neither death nor life, nor angels, nor mysterious powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation.” This is no premise to be grasped; it is a rich verse to be embraced and assimilated into one’s life at the very deepest level. Certainly this poetry is why I am so moved by the astonishing waves of sound that a Mahler symphony produces, why a Beethoven string quartet resounds in the ear, why Erich Korngold’s plaintive main song from his opera, “Die Tote Stadt,” never fails to move me deeply. The poet comes in many guises, in words, in paint, in sound. It is only when I imagine that there are certain axioms I must embrace, certain beliefs I must affirm, certain verses I must repeat, that I begin to question whether my faith is strong enough to face the fears of an eye surgery or the inevitability of aging and death. But in the realities of poems and paint, in the sublimities of sounds both symphonic and chamber, I find the truth and the power of my God.

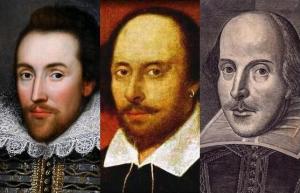

In the wake of Mahler and Beethoven and Korngold, in the light of Rembrandt and Titian and Caravaggio, among the words of 1 and 2 Samuel and Job and T.S. Eliot and Phillip Larkin, I hear the unmistakable voice of my God, and I find a certain rest from my fears, a specific calm for my anxious spirit. How grateful I am for our poets! In their wonderful light, I see the light of God, and I can live my life with joy and hope, even as my eyes dim and my years are heavier upon me. God speaks through them to me, even through those whose own connection to God was weak or non-existent. When I face my surgery next week, that Korngold song will sing in my head, and I will know that God is with me. Thanks be to such a poetic God!

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)