Over this turn of the “Wheel of the Year”, it’s my plan to investigate and pay respect to eight archetypes of mature, sacred masculinity. This is the second installment in this series.

Context

Men’s mysteries matter. Today, young men are confronted on one hand with reactionary voices who advocate for gender roles decades or centuries out of date, and on the other with professional-managerial class “progressive” voice who seem to think the answer to the reactionaries is to eliminate masculinity.

The transition to manhood is dangerous. Men are both more likely than women to be murdered and to commit murder. We’re more likely to be in prison, to be killed on the job, or to commit suicide. We’re less likely to finish high school or earn college degrees.

Boys who fail to make a successful transition to manhood end up at best being a drag on society, and at worst an active threat to people’s lives. And we will not help them make the transition by denying that manhood even exists.

To help young men through the transition, a system of archetypes can be a useful guide. No such system will be complete, of course. What I’m going to talk about in this series of posts is inspired by the book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover by Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette, and also by Robert Bly’s work, but it’s my own thing. Anything smart is probably copied from those others and anything dumb here is probably my own fault.

By considering these archetypes I am not claiming that these roles are unavailable to women or nonbinary folks. Nor am I claiming that this is the only way to be a man. I’m offering some ideas that have helped me come to terms with my own existence as an adult male human being. (And cognizant that that is as a “white” heterosexual American male, though still believing there’s enough universality in the way androgens shape our brains for the exercise to be useful). If they don’t work for you, fine, please tell us your secrets! If you’re not a man and find that they work for you, great!

For each of these archetypes, we’re going to discuss a balanced version, an excess version, and a shadow version.

Visualize us going around a mountain: at the top is the Wild Man and the realm of excess, up where the air is thin. It’s exhilarating but we can’t stay there. At the bottom is the shadow realm of fear. The healthy mature man moves around the middle heights of the mountain, in neither shadow not excess, moving between the archetypes as needed. Over this series, we will visit eight points around the mountain: the Magician, the Healer, the Lover, the Preacher, the King, the Captain, the Warrior, and the Trickster.

The Healer

Let’s start our consideration of the Healer with Stanley Krippner’s definition of the shaman:

…a particular type of practitioner who attends to the psychological and spiritual needs of a community that has given him or her privileged status. These practitioners claim to engage in specialized activities enabling them to access valuable information that is not ordinarily available to other members of their community. Hence, shamanism can be described as a body of techniques and activities that supposedly enable practitioners to access information not ordinarily attainable by members of the social group that gave them privileged status. These practitioners use this information in attempts to meet the needs of this group and its members.

(Longtime readers of TZP, or readers of Why Buddha Touched the Earth, will note that this is a slightly different sense of the word “shaman” than when comparing shamanistic religion to priestly religion.)

The archetypal Healer has access to special knowledge. Whether it’s a tribal shaman’s relation with the spirits, a traditional herbalist’s memorized lore, or a modern physician’s skills and diagnostic tools, the Healer knows important things the average member of their society does not.

But unlike the archetypal Magician, who is isolated in study of his art — the wizard in his tower — the Healer is applying that art for the benefit of others. While there may be differences in applied versus theoretic or abstract knowledge, what really sets the Healer apart from the Magician is this connection to others.

And that connection is on an individual but impersonal basis. While the King (whom we’ll consider later in our series) has a role in the healing of the community as a whole, and the Magician in his tower as the scientist in his lab may develop great cures that help people, the Healer works with people as individuals. But unlike the Lover (also to be discussed later) the Healer does their work not just with a few beloved, but with all people — at least all members of their own community or tribe.

The Healer is a clinician, not a researcher. He relates directly to people. So it’s no surprise the that lives of Healers are fodder for many TV dramas, from Dr. Kildare to General Hospital to M*A*S*H to Grey’s Anatomy. The very nature of the Healer calls for emotional involvement, and that has dramatic potential.

As a boy raised on Star Trek, of course my own main fictional go-to for thinking about the Healer is Dr. Leonard “Bones” McCoy. While we sometimes see him in his lab, like we might find the Magician, it’s always in search of a specific treatment for a patient, not in abstract research. And out of love, he’ll treat anyone, even the “evil Spock” from an alternate universe, or a silicon-based monster. He even is willing to sacrifice his own life to save his friend Jim Kirk and his frenemy Spock from death by torture (“The Empath”).

The knowledge of the Magician, applied with the affection of the Lover: this is the Healer.

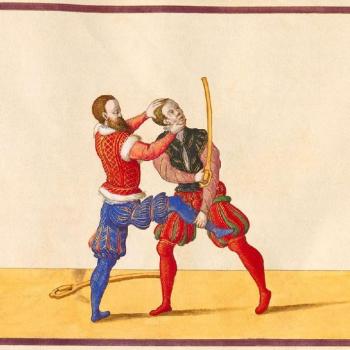

Shadow: The Sorcerer

The Sorcerer takes his knowledge and applies it to manipulate others rather than to benefit them. The term “sorcerer” is often used in anthropology to refer to individuals with the same source of power as shamans, but who use that power for ill ends.

Another way to describe this shadow archetype is a “svengali”. The word comes from a character in the 1895 novel Trilby by George du Maurier; Svengali is a hypnotist who manipulates and controls a young and innocent woman. As Rebecca Housel writes, “the term “svengali” refers to a person who uses emotional abuse to control another (usually someone younger, creative and innocent/naïve)…People who bully us. Railroad us. Control us. Convince us that what we know to be wrong, is absolutely right. And there is something really wrong with us for thinking otherwise. Basically, a svengali holds you emotional hostage.”

The Sorcerer or svengali has the same sort of knowledge as the Healer, and like the Healer interacts with people on an individual level. But they do so for manipulative ends rather than for healing.

Excess: The Burnout

“We were gonna save the world, man.” The Burnout had great plans to help everyone but flew too high, didn’t acknowledge limits.

Unfortunately this archetype forms all too much of the reality of contemporary medical training. As Michael Greger writes in his book Heart Failure – Diary of a Third Year Medical Student,

I saw medicine as a humanistic career of intimacy – helping people, sharing, caring for people. But what I found was a profession that didn’t even seem to care about people. No one around me seemed to question what was happening to them, to the patients, to all of us. As Michelle Harrison wrote in her book A Woman in Residence, “I came to feel I had been fighting a war which no one else even knew existed.”

…

From an interview in Redbook, Dr. Spock on medical students:

[The sociological study] showed, discouragingly, that the level of interest in patients as people was high on entering medical school, went down precipitously during the four years of school and the years of internship and residency and reached a low point at the start of practice…. Unfortunately, when departments of psychiatry tried to teach students in the third and fourth year of medical school about people’s feelings – including their own – they found that many students had already developed such a deeply impersonal attitude that it was difficult or impossible to warm them up.

…

Missy had leukemia – now in remission thanks in part to yellow bags of methotrexate that follow her as she rolls around the floor. When I fall to my knees she runs to hug me. I sit on the floor and we play you-look-in-my-ear-I-look-in-yours. She drew a smiley face on my hippo and named the stethoscope beanie rooster “Elvis.” She paints me pictures and signs them “FROM MISSY.” I paint her nails and she paints mine – a lovely purple-brown. I wore them to rounds this morning.

My senior resident took me aside. “Your fingernails are getting in people’s way,” he said. Huh? “The attendings are complaining; this is a conservative profession.” Defensively, I tried to explain that I didn’t paint them myself, mad that I even felt the need to explain at all. He knew. He knew that she had done it. He replied, “Medicine is also an anti-emotion profession.”

To be a Healer, a care-taker, helping all who come, is an enormous responsibility. It can have enormous rewards. But it also has enormous stresses, inherently. And because the sorcerer and the shaman — here, the greedy or status-obsessed physician, and the genuine Healer — draw from the same power source, trying to keep the energies straight becomes another source of stress.

So the Healer must take care to acknowledge their limits, to do the work of self-care, and to accept the healing work of others to avoid burnout. As the cliche goes, “Doctors make the worst patients.” Don’t be like that.

The Healer (Shaman/Smith) at Imbolc

Everyone has heard of the solstices and equinoxes, as basic astronomical events. And of the cross-quarter days, everyone has heard of Samhain, and many have heard of Beltane. Lammas and Imbolc, though, get little attention outside of Neopaganism.

In the reckoning of the seasons that makes the solstices mid-summer and mid-winter, Imbolc is the start of spring. While in North America (or at least the eastern United States) February is often the coldest month, we are leaving the darkest quarter of the year. Sunshine is increasing, and trees are starting to produce visible buds. The energy is shifting even if sustained warmer days are a few months off.

(The question of whether Imbolc or the equinox represents the start of spring comes to us as the only survival of Imbolc in the general calendar, Groundhog Day.)

We know that the Irish celebrated Imbolc centuries ago; it’s mentioned in the epic poem Táin Bó Cúailnge (“Cattle Raid of Cooley”). Somewhere along the way it became associated with Saint Brigid of Kildare, who was in all likelyhood a Christianization of the ancient Irish goddess Brigid.

Both the saint and the goddess are associated with poetry, healing, and blacksmithing. That may seem like an strange combination, but I’d like to suggest that there is commonality in these activities

The link between poets and magic is as old as the word. Shamans have directed healing magic since before the dawn of civilization. And many cultures have regarded blacksmithing as being having magic to it, from the Eastern Buryat people of Siberia’s belief that the blacksmith received his abilities from the gods and had the same status as the shaman, to European folktales like St. Dunstan grabbing the Devil by the nose with his blacksmith’s tongs.

Though just as the power of the shaman creates accusations of black witchcraft and placed the inheritors of the shaman’s path on the edges of many societies, so the power of the smith — the forgers of weapons — has led them to be made outcast in some societies.

Poetry, metalsmithing, and healing all take deep learning and apply it for the benefit of the community. While we’re calling this archetype the Healer, perhaps the Smith might be just as good a label, or at least offer a handle on him for those whose work is with the inanimate more than with other people.

And this time of Imbolc, when we celebrate a patron goddess of healing, poetry, and smithing, seems a good opportunity to consider an archetype of healing who we can also connect to these other fields.

So take some time this season to consider your relationship with this archetype. What skills do you apply directly in the service of others? Do you connect with others while maintaining appropriate boundaries?

Do you practice self-care, and receive care from others, so that your own caretaking can be sustainable?

Evocation of the Healer

I evoke and call forth

The Healer within me

I honor and acknowledge

My ability care for and connect with others

Through my special skills and knowledge

I resolve to maintain appropriate boundaries

To care for all in need without prejudice or bigotry

To never manipulate the vulnerable

To care for myself

To accept the care and help of others

So mote it be.