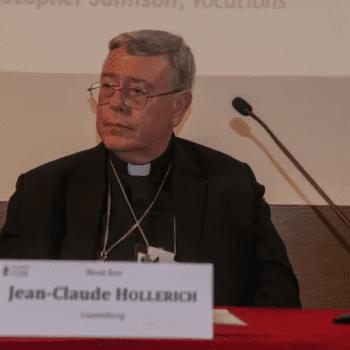

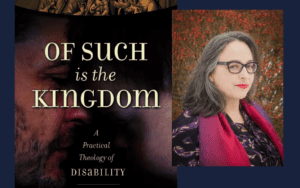

Summer Kinard, Of Such Is the Kingdom: A Practical Theology of Disability (Chesterton, IN: Ancient Faith, 2019).

Summer Kinard offers a great selection of thoughts on disability theology and ministry in Of Such Is the Kingdom. I think they will contribute to the wider discussion of disability among Christians. I would recommend her book. Protestants have developed a bit of a theology of disability, but among Churches with sacramental realism (i.e. Catholic and Orthodox), this is the first attempt at a comprehensive work by a single author.

I want to share some of Kinard’s reflections below, following her outline, then note a few imperfections I see in her work. Her outline is an introduction followed by sections called Kairos, Theosis, Kenosis, and Koinonia.

Introduction

She begins by asking why we need a practical theology. To explain this, she gives a story: she walked along with a student in a wheelchair when someone told them, “If you will believe in Jesus, you can stand up out of that wheelchair and walk.” She thought, “How dare he attack this woman, who has devoted her life to studying the Lord, as though she lacked faith?” However, her student came to the rescue first, “Sir, this wheelchair is an answer to my prayers. I know Jesus, and he gave me this wheelchair so I can fulfill the call he placed on my life” (14).

Then she gives here reason more systematically: “We need a practical theology of disability so that we can give a word in season an answer to the hope that is within us, right in the midst of the challenges of life” (15).

Kairos

She ends this section with possibly the most powerful lines of the whole work: “The creation of the human being was finished when Christ died on the Cross, and we can only become human by participating in Christ’s death. What that means, and this for me is very important to understand, is that special needs children or disabled people generally are not disordered images of the rest of us. This is what the DSM would lead you to believe – it is a manual of disorders” (67).

Kinard notes that Church teaching reflecting on the disabled, “emphasiz[es] that disabilities are given to us in order to reveal God’s work among us in various ways, including spiritual consolations, opportunities for virtue, or healings both spiritual and physical” (36). Thus she wants to emphasize that the mission of every Christian – disabled or not – is to live Jesus’ two great commandments of loving God above all else and loving our neighbor as ourselves (38).

She also notes how we can unfortunately at times see the disabled as distractions. If we see disabled members of the Church simply or primarily as distractions, we hinder them and their families from being full members of the Church (52). Instead, that distraction should lead us to pray for them (60). In such instances, small gestures to help or avoid judgement can be key (58).

Theosis

This is by far the longest section of the book. Kinard wants us to see each person as Jesus does: “He or she is sacred and loved and welcomed, as we would welcome holy angels or Christ himself” (84). We can lead them to divine life through sacraments, prayer, and virtue.

Kinard wants to emphasize a sacramental vision for all people, disabled or abled. She notes, “We are surrounded by a culture that denies the incarnation and therefore denies the sacred importance of the body. As a result, because we might have picked up on the disembodied chatter of our surroundings, we sometimes put more emphasis on what we can understand mentally than on what we can receive physically” (129-130).

Even if someone lacks the ability to do something the most common way, that does not mean that they can’t do it at all. Regarding vocal prayers, she explains, “It may seem to be a paradox to say that we can love and follow the Word of God without words. Yet, for many people, prayer must often or always be without speech” (157).

Kinard notes that so often it is simple to welcome a family of a person with disabilities. Lots of time what is most important is reaching out and caring for them individually, not just assuming all is fine.

Kenosis

Kinard has a long explanation here on the differences between the sexes and how that points to not only one way for a body to be holy. She then extends this to a disabled body, noting that Disability is not an impediment to holiness. She summarizes it, “Just as humans, male and female, are made in God’s image and can be holy, so people without and with disabilities are made in God’s image and can be holy” (192).

She also notes that certain disabilities, notably social and developmental disabilities, also prevent people from asking for help so we as a Church should reach out to see if they need help. She explains that we need to explain the Gospel in a way suited for these people’s brains and we need to make disabled persons active participants in the mission of the Church, not just passive recipients (187, 202, 211).

Koinonia

This was relatively brief and most of the practices she recommends for welcoming the disabled in the community are widely known, so I won’t go into details. She does note a deeper spiritual meaning to this though: “Our welcome of families with disabilities is an extension of the hospitality of God, who has drawn near to us in Christ” (229). She applies this idea in welcoming the disabled such as finding good gluten-free snacks similar to what the other children can eat. Kinard also notes, “Shushing is meant for the devil, not for disabled children. Don’t do it. It doesn’t help, and it turns away the children whom the Father has called to himself” (239).

Imperfections

I saw two major imperfections in this work: neither sink the work but are worth knowing as you read. First, she seems to mix everything from very high theology to very practical suggestions, which can be good. However, at times, I would not know which a chapter was going to be before reading. Even though the same person wrote almost the whole book, the chapters sometimes felt more like a group of presentations at a symposium. Second, related to the first is that I think she makes a bunch of great points that can contribute to a complete theology of disability, but I do not see this work as presenting a complete theology of disability on its own. These should not take away from the great steps Mrs. Kinard has made, and might almost be expected in an early work trying to encompass a complex theme like disability comprehensively. Also, I think we Catholics tend to like the systematizing and distinction-making like I suggest more than our Orthodox brethren: this is in no way a critique or Orthodoxy as I see this as variations in valid styles or modes of doing theology.

I hope that this book helps you understand the theology of disability and I hope it is a starting point for further reflections on disability by Christians. We can end with something she says near the beginning and something she says near the end. “Disabilities do not embarrass God. Rather they are for our salvation and to reveal the glory of God” (18). And, “Persons with disabilities… shine forth the truth that nothing can separate us from the love of God” (262).

I hope you enjoy Of Such Is the Kingdom: A Practical Theology of Disability.

Notes:

- I received a free review copy of this book from the publisher.

- I wrote this in Spring 2020 and thought I had sent it to an academic journal for publication then realized I’d sent a different book I reviewed at that time.

- Please support me on Patreon so I can keep writing more analysis of Catholicism and autism.