With the theaters cram-packed full of broody dystopian action (Catching Fire), agonizing Oscar bait (12 Years a Slave) and mindless explosions (lots of things), Nebraska has a different take.

The film starts small, slowly building to deep belly-shaking humor and a warm affection for its Midwestern subjects. Like the road trip that fills the bulk of the story, it’s a ride that feels awkward and even pointless at first, but one you’re sure glad you took by the end.

Saturday Night Live alum Will Forte stretches his acting chops in the lead as a rudderless man-child David Grant, treading water in Billings, Montana. His job selling stereos pays the bills and his Subaru gets him places. When his girlfriend insists they either marry or split, he honestly cannot say which he prefers.

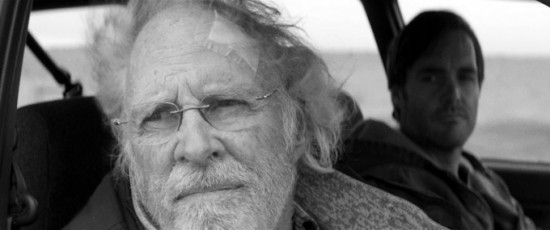

The only unpredictable element of his life is the increasingly senile wanderings of his father Woody (Bruce Dern). Convinced he has actually won a million dollars from the publishing sweepstakes, Woody sets out for Lincoln, Nebraska – by foot no less – to claim his prize.

Repeatedly. He’s chased, bundled into a car, returned home, and watched carefully, only to bolt again at the first opportunity.

He’s a taciturn man, a lifelong alcoholic, and not much of a father. So when David volunteers to drive dad to Nebraska in search of his nonexistent prize, the audience is as baffled as David’s mother by the gesture. But not more baffled than David himself. “Why the hell not,” seems to be the attitude, “Might as well.”

You think you know where this is going: revelations that lead to apologies and forgiveness, a sense of understanding between father and son.

All those things come, in a sense, but via unexpected routes and understated interactions. Somewhere around Hawthorne, Nebraska, they cross the border to utterly sublime and completely ridiculous, a combination that works here. When the family, reunited along with mom and David’s brother Ross (Breaking Bad’s Bob Odenkirk) engages in some cornhusker hijinks, it’s a humor that comes from deep within the characters.

And the audience realizes that, like David, they’re having a good time.

Part of the joy of this film is the way it revels in and relishes the Midwest. One fantastic scene shows elderly brothers, reunited after many years, catching up as only Midwesterners know how: “You still driving that Chevy?”

The casting of bit characters and townspeople, as my friend Nell Minnow pointed out to me, is excellent. Their faces are lined, rutted, friendly. Eyes clear, bright, smiling. Accents with the long vowels recalling days gone by. These are Midwesterners, not some trumped up Hollywood version of fly-over country. Filmed in black and white, which you forget to notice after about two minutes, the camera lovingly caresses the empty fields, long roads, big skies, and workaday buildings of God’s country.

That’s not to say that this movie will appeal to all Midwesterners. Rated R, it has a definite potty mouth. All the characters are grating at first, especially David’s mom Kate, played by June Squibb. She’s loud, angry, bitter, and belittling. One can see why Woody drinks. She’s as crass as Lady Gaga, not afraid to detail the boys who once tried to get into her bloomers, played for great humor coming from her grey-headed, grandmotherly face.

The beauty in this film is that it finds the pathos in the abrasive characters. It’s not that they change, but that David’s – and our – perception of them changes. At the beginning, we only want to escape Kate. By the end, we love her, and Woody too.

It’s not just a story of understanding the person who happened to become one’s father. It’s about embracing family for who they are instead of who we wanted them to be, along the lines of Little Miss Sunshine.

And it’s a story of facing death as well, as Bruce Dern brings us a SOB on his last, great caper. Woody is fading, Dern makes that magnificently clear, but in the fading we see the blaze of the man he is. His final triumph, writ small in the main street of a dying town, has an epic quality.

Plus, it’s quite funny.

You should see it. It’s a love song to ordinary men and the ordinary towns in which they live.