Some fellow tippling philosophers and myself are having an email exchange about psychology. It started with one of us writing an email lauding Daniel Kahneman’s work Thinking Fast and Slow, and with another TPer critiquing that (the bold is where he is quoting Andy, the first person).

Kahneman has spoken.

Kahneman’s first commonplace is

do not trust anyone – including yourself – to tell you how much you should trust their judgment.

That is, except for him as his judgement is somehow free from the lamentable schoolboy errors he tells us we all make on a daily basis. How fine to live on the Olympian plateau he inhabits while we grovel around down here in a sea of our own grime, heuristics and biases.He then produces a string of homespun bromides and platitudes such as:

The way to block errors that originate in System 1(Intuition or thinking fast) is simple in principle: recognize the signs that you are in a cognitive minefield, slow down, and ask for reinforcement from System 2(Computation or thinking slow).

Anything that occupies your working memory reduces your ability to think.

Superficial or “lazy” thinking is a flaw in the reflective mind, a failure of rationality.

The common admonition to “act calm and kind regardless of how you feel” is very good advice: You are likely to be rewarded by actually feeling calm and kind.

Biological fact: an organism should react cautiously to a novel stimulus, with withdrawal and fear.

Death by accidents was judged to be more than 300 times more likely than death by diabetes, but the true ratio is 1:4. The lesson is clear: estimates of causes of death are warped by media coverage. The coverage is itself biased toward novelty and poignancy.

A friendship that may take years to develop can be ruined by a single action

A single cockroach will completely wreck the appeal of a bowl of cherries, but a cherry will do nothing at all for a bowl of cockroaches.

Tell me something I didn’t know already! But, of course, it’s all dressed up in psychobabble gleaned from the assumption that a human being is the same as a lab rat, and suddenly it wins the Nobel Prize (Economics -sub section – Emperor’s New Clothes – subsection – the Bleeding Obvious)!

He talks about the superiority of ‘Computation over intuition’ which amounts to no more than ‘Fools rush in where angels fear to tread’ or ‘Act in haste, repent at leisure’, which, I believe, pre-existed the arrival of Daniel Kahneman on the scene.

Did you know the word ‘gullible’ has been removed from the dictionary?

For a very short and more sane Youtube video appraisal of the situation see below.

http://www.newrepublic.com/article/114172/leon-wieseltier-scientism-and-humanities

Of course, you don’t have to trust my judgement on anything.

Guy

Guy has actually got misreading of Kahneman here. More accurately, from Kahneman himself:

Besides, relying on computation instead of intuition would, according to Kahneman, create a slow, laborious, difficult, and costly world. What he did advocate is paying closer attention to the onset of faulty intuition.

“The alternative to thinking intuitively is mental paralysis,” he said. “Most of the time, we just have to go with our intuition, [but] we can recognize situations in which our intuition is likely to lead us astray. It’s an unfinished story.”

And then Guy continued:

‘One’ doesn’t even exist. We are all busily abolishing ourselves and the responsibilities of selfhood by accepting that we amount to no more than a bunch of biases which we can’t escape (unless, of course, our name is Kahnemann, who found the power to become aware enough of his biases to be free of them. I wonder when and how he decided he had reached this point. How did he know he was no longer subject to bias? Perhaps it never ends. At some point he arrogated to himself the right to pronounce himself free and to be capable of pronouncements worthy to be attended to by other mortals. Like Moses handing down the ten commandments).

I responded to this as follows:

Are you doubting cognitive biases? I am not sure what you are getting at. There are shed loads which are hugely pervasive, and evidenced by shed loads of empirical evidence, not least by people like Kahneman himself.

Good place to start:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_biases

I would direct you to my good friend Dr Caleb Lack, Great Plains Skeptic, who teaches about cognitive biases. Incidentally, I recently edited a chapter of his for an anthology, on cognitive biases!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKhzr0dc2q8

By saying “Tell me something I don’t know” you seem to be claiming that these are obvious, then calling them into question by attacking Kahneman and/or his work…?

Actually, Kahneman, as far as I know, advocates both strategies [intuition and rationality] since one without the other always seems to end in problems (see the work of Antonio Damasio on precisely this).

This email included reference to our very own Great Plains Skeptic here at SIN. I have to say, I was somewhat surprised by Guy’s response which goes to the heart of the matter:

The institution of Psychology with its libraries of authorities, of course, justifies and sustains itself. I am taking issue with the discipline of Psychology so it would be pointless to submit myself to ‘proofs’ from people who are already sold on it. My point is that I am not sold on it. I have taken time to write a considered response to Kahneman’s standpoint. It’s called:

Daniel Kahneman – Thinking, Fast and Slow

and is the most recent post on

Roseatetern.blogspot.co.uk

Guy

This crazy epistemological approach inspired me to say:

Of course, that logic works entirely against you and a sound epistemology too:

A Creationist announces:

“I know the truth of the Bible! Why would I want to listen to the words and work of scientists if I reject what scientists have to say! I am taking issue with the discipline of Science so it would be pointless to submit myself to ‘proofs’ from people who are already sold on it.”

(substitute “science” with any discipline).

In other words, you isolate and insulate yourself from changing your mind by refusing to listen to the relevant experts in the field which you are rejecting.

Guy offered his riposte:

I take issue with only one particular discipline here – Psychology the authority of whose ‘experts’ I don’t accept. I’m very happy to accept the discipline of medicine for example as it is studying the merely physical aspects of humans. I don’t accept the authority of psychologists because Psychology is founded on casual and fallacious premises that neglect to define the area of study in a satisfactory way. It casually presumes to study human beings without first establishing an incontrovertible model of what a whole human being is and, therefore what the range of the area of study is. It’s not self-evident in the same way as the being of an animal is. It cannot be encapsulated so easily as there is huge range of conflicting models available. Also the fact that a human is studying humans is problematic. How does he detach himself from the interfering inferences and assumptions that humans make? How can he, therefore be truly scientific in a disciplined way? Perhaps I’m saying that he comes with, dare I say it, biases and cannot presume to accuracy in his data. Using the rat template won’t work for all of these reasons and will lead to spectacular mistakes.

Guy

PS How do you deal with the fact that ‘experts in the same field will often disagree and become involved in vitriolic arguments? By your lights the poor layman has to listen to them all and believe them all even though they disagree. Its best to think freely and make your own mind up after giving experts due cognisance.

Let me just say here that disagreement is part of the scientific method and gets sorted, in due course, with more understanding and knowledge, by the scientific method. That is what both philosophy and science seeks to do (science originally being called natural philosophy). What does “thinking freely” mean? That one can just believe what they want irrespective of the evidence? Well, sure. But it most probably won’t be correct or true in any meaningful sense of the word. Is it a good thing that I might believe that the moon is made of cheese? Is that really what freethinking entails? Yes, let’s be iconoclasts if that furthers our knowledge in some way, but to do so just for the sake of it isn’t so worthy.

Another problem here is that he conflates a human with a human being. Psychology looks at why people do things (in very simple terms), not what a human being is. It doesn’t need to concern itself with what dictates personhood. Understanding confirmation bias or the halo effect has little to do with the philosophical argument of how a human being is defined in terms of personhoood! Essentially, his point here is a non sequitur.

Let me include three more exchanges before summing up. First from me:

The Psychology of the “Psychology Isn’t a Science” Argument

Is worth reading. I would also ask how deep your knowledge of psychology is. Perhaps you are stuck in old-school views of, say, (Skinner’s) Behaviourism as opposed to more modern cognitive psychology, or any other field and subfield. I imagine, since Rob [a friend and founder TPer] is just about to embark on a Masters in Psychology, that he might have something to say on the issue!

Yes, there is pseudoscience in psychology, as there is in many fields. And yes, one must define what is meant by science. But as knowledge goes, psychology is right in there. And as a teacher, I would be amazed if you didn’t use psychology on a day to day basis with your pupils. It is the bread and butter of our pedagogy.

I have to admit, your comment here really surprises me!

To which Fiona, who has guest posted here, chipped in with:

What disturbs me about psychology and books like Kahneman’s is that the business of existing is becoming a science where everything has to be labelled and categorised. Apparently 1 in 4 of us suffer from some form of mental illness. But who decides what it takes it to receive a diagnosis? Surely these apparent mental illnesses are just part and parcel of being human? We seem to have this need to make life perfect, to not suffer or experience negative emotions. And if we do a pill or a psychologist will make us better. Is it any surprise that so many are mentally ill when we live in a culture where the messages we constantly receive are that we should be somehow different or better? And that books such as these are making us feel that there is something wrong with the way that we view our world?

It appears to me that in trying to make sense of what it is to be human we are dehumanising ourselves. We are all encouraged to modify our behaviour, to feel that if we do something else, or change some part of ourselves we will be somehow improved.

We are not computers but it does seem that we are being “scienced” into being just this.

What all this research seems to do is lead us down the path of feeling that just “being” is not enough.

Fi

This was interesting because it has come up here a number of times recently and it has also been a topic of conversation between myself and another TPer, the Rob mentioned above. I replied:

Funnily enough, Guy, I met with Rob for lunch the other day.

We got to talking about personhood. My ideas of personhood are defined precisely by my philosophy on abstract ideas and existence properties. I have a problem with a lot of philosophers, theologians, thinkers, etc who make claims about, say, personhood, or morality etc but who have not done the more fundamental work.

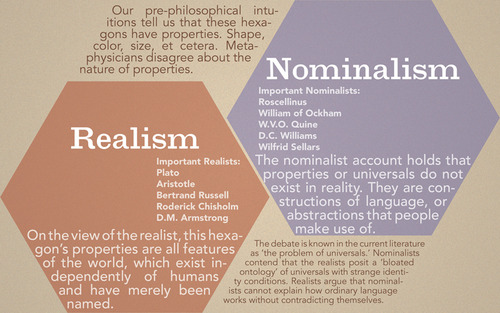

To claim that personhood has ontic reality, ie that it is a real and existent thing, is problematic. What you need to do first is establish what abstract ideas and concepts are made of. This is why I am always saying to Rob that THE most important debate in philosophy is the abstract one: realism vs nominalism and conceptualism.

As a conceptualist, I find it hard when people make big claims about big ideas (morality, personhood) without realising that these are human concepts, and aren’t objective facts. Or at least, if they are, the claimant needs to show that they are by establishing something akin to Platonic Realism which is really hard.

So although some of the things you and Fiona are saying here might sound nice and sort of ‘ring true’, this far from establishes that they ARE true. I have reassessed many of my beliefs about the world in accordance to what we can assess about abstract and existence properties. The problem, unfortunately, is that it is a very dry and complex area of philosophy (when you get on to trope theory and particulars).

Whether one is prepared to enter into such an fundamental debate is anther question. But I DO suggest that if we want to get to the bottom of such claims, it is hard to do so when arguing many levels up in areas which clearly supervene on this more fundamental area of philosophy.

This is not only a lot of reading, but some of the entries need lots of re-reads and head scratching and pondering.

nominalism

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nominalism-metaphysics/

abstract objects

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/abstract-objects/

properties

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/properties/

natural kinds

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natural-kinds/

tropes

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/tropes/

Types and tokens

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/types-tokens/

Medieval Problem of Universals

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/universals-medieval/

Platonism

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/platonism/

Propositions

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/propositions/

Now, I have not included every response here as that would be tedious, but the final one I want to include is as follows:

Jonathan,

I’m not going to read that long reading list. Firstly I’m going to quote you:

As a conceptualist, I find it hard when people make big claims about big ideas (morality, personhood) without realising that these are human concepts, and aren’t objective facts.

Then I’m going to refer you back to Roger Scruton’s propositions about the impossibility of studying the human person as an object (which agrees with what you say). The fact that we can’t do this doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist (or has ontic reality as you say). Indeed, in our interactions with each other, in our very pretension to make utterances that signify and have value, we cannot help but assume that it does exist. The problem is that it pre-exists our discussion of whether it exists. Unless it did we couldn’t begin to discuss anything. There’s the rub! There’s the glory and mystery of the human condition. We have to accept and assume something we can’t prove. Otherwise we can’t even get off the ground and interact as people. Something of a wondrous paradox which won’t submit to the exigencies of explanation. Perhaps this says something about the status of human reason. Irritating isn’t it?

Guy

What do I make of all of this and why do I bother making a post of it? Well, it is partly this notion that psychology is ill-defined and not worthy of being a science, partly because of some of the crazy logic, and partly about this idea of mystery being important to humanity and personhood. Yes, that’s a lot to get through, so let’s get started.

What I find fascinating is that there is a move from a couple of the TPers here to distance themselves from Psychology with a big P as it is cited. The problem is that these people seem to be happy to use and refer to psychology, I’d wager, when it suits them. I am not sure they realise how much psychological knowledge derived from scientific, testable methodology, they use and have accepted in their lives. It seems to me that these people are happy to rubbish psychology because they straw man it; they have erected an edifice built of pseudoscience, poor psychology and woo quacks and called it Academic Psychology. Well, I would not ascribe to that nonsense. Evidence-based, good clinical and research-based psychology, on the other hand, warrants a lot of attention. Making hasty generalisations of psychology and poisoning the well is a rather silly way to go about things.

It would be useful if these other TPers actually defined the psychology with which they take issue. As with all arguments and philosophy, defining your terms is incredibly important.

It is this quote which most annoyed me, I think:

Of course I use psychology with a small p in the classroom. That just means, and, again, I flatter myself here, I have accumulated some wisdom about human relations. In this sense good teachers, long before the invention of the academic discipline of Psychology with a big P was invented, used psychology (I’m sure Socrates and Aristotle did). Psychology and psychology are not the same thing though.

So psychology is fine, if practised and collated individually. But when we make a discipline of it, it thereby becomes impotent, ruined, ridden with fallacy or some such other issue? So is this the case with every academic discipline? Or just psychology? What about academic psychology is so terrible here? It annoys me that the amazing work on, say, priming studies is somehow invalidated by this most sweeping and incoherent generalisation. So work which I have detailed, say, here and here, or maybe here, is by definition of being academic psychology, invalid and unworthy of contemplation? Personally, I find the psychology of religion more rewarding a subject, and more forceful and telling, than theology and to some respect, philosophy. It is a case of normative vs descriptive. What we would like the world to be or how it should be is a far cry from what it actually is. And psychology is interested in that descriptive aspect – why do we act, believe, behave like we do? To give psychology a bad name in this way is nonsensical to me. To see this discipline as, I don’t really know what, but somehow responsible for dehumanising us is mind-boggling. In fact, psychology tells us what it means to actually be human by point of fact it tells us what we do behaviourally, and why. How our minds work.

Looking at some of what Fiona states, it is clear that there are some further issues. Perhaps it is a misunderstanding of what psychology is and what psychologists do and believe.

Apparently 1 in 4 of us suffer from some form of mental illness. But who decides what it takes it to receive a diagnosis?

As Dr Caleb Lack, SIN psychologist, has written on a recent post:

Although some would argue, PTSD does not seem to be a new phenomenon, with accounts dating back fairly far in written history. It also appears to be as well validated a diagnosis as most other mental disorders (which are, in and of themselves ,social constructions, as are medical disorders, but this does not mean they are “made up” or not real. I’ve written a whole series of posts on how we define psychopathology, so I’m not going into detail here). Specifically, persons with a diagnosis of PTSD display three broad groups of symptoms:

These social constructions, though, are pragmatic. That is why, indeed, they have sprung up. We label both physiological illnesses and mental illnesses abstractly, like we label anything. But they represent real things. There really is stuff happening in your body, your brain and your consciousness! Fiona continued:

Surely these apparent mental illnesses are just part and parcel of being human? We seem to have this need to make life perfect, to not suffer or experience negative emotions.

AIDS and cancer are part of being human, by the same token. Does that mean we should not fight these things? Old age? Colds, coughs, sore backs, broken arms? This logic means that we should not also academically research medicine and health care! Separating the mind/consciousness out from its physiological setting (ie the brain and the body) is insane. I suggest reading work on emotions to let you know that these psychological conditions are best understood in their physiological an even evolutionary contexts. Dr Valerie Tarico does a superb job of showing this in her chapter of Loftus’s The End Of Christianity in order to show that God, being non-corporeal, has no need of and makes no sense in having psychological emotions.

Maybe Fi (and this is perhaps to some large degree the case, knowing her) is an extreme naturalist (environmentally so, meaning nature) and wants humanity to ‘get back to nature’. But then you would eschew all remedies and attempts to find cures for things, or sort problems out. Just let nature be. Psychology is pretty organic when one talks about many of the behaviour therapies etc. Fiona needs to be careful not to confuse psychiatry with psychology here, too, as Guy’s wife was at pains to tell me in another email (though I think that she would be better to have aimed that at Fiona’s comments as I am all too aware of such differences).

And if we do a pill or a psychologist will make us better. Is it any surprise that so many are mentally ill when we live in a culture where the messages we constantly receive are that we should be somehow different or better? And that books such as these are making us feel that there is something wrong with the way that we view our world?

So here we are really getting on to a misrepresentation of what psychology is. One must be aware of the differentiation between psychology, clinical psychology, psychiatry and psychotherapy; and even the difference between these things between the UK and the US (e.g. UK psychologists cannot prescribe medicine).

It appears to me that in trying to make sense of what it is to be human we are dehumanising ourselves. We are all encouraged to modify our behaviour, to feel that if we do something else, or change some part of ourselves we will be somehow improved.

We are not computers but it does seem that we are being “scienced” into being just this.

There is lots to take issue with here. I think Fiona is imagining everyone is psychologically perfect or like her. The problem is, the world is replete with psychopaths, sociopaths, depressives and the like. Maybe we should leave psychopaths to their own devices and not interfere with their ‘natural’ inclinations! Maybe we should not try to understand autistics… Or should we be tying to make the world a better place by understanding how things and people work, helping to make them happier?

Now, it seems that Guy, as a teacher and according to his earlier quote, just relies on his small p psychology to do his work well. Perhaps he has not taught severe autistics and people with Asperger’s Syndrome in his teaching career. I have. And to think that academic psychology isn’t of great help in this area is sheer nonsense. I have had training sessions delivered by educational psychologists which have been fascinating and insightful. I meet very often with educational psychologists to help my behaviour management of the statemented children I have who are on the spectrum, who are very difficult to manage. So it kind of pisses me off when “Psychology” is just rubbished in such a trivial and naive way, as if it has nothing to offer. As if the discipline hasn’t opened the autistic world up to be understood better by the neurotypical world. Whether it be ground-breaking experiments like the Milgram of Stanford Prison experiments, or whether it be Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Mischal’s Delayed Gratification work, Piaget’s development models, or the priming work of Pisarro, work of Gervais and Baron Cohen on autistics, understanding of the bystander effect, halo effect, placebo effect, Lucifer effect, yada yada yada, psychology is massively informative, pragmatically applicable and, well, scientific to boot.

The more I think about it, the more I think these TPers have little understanding of the scope and findings of academic psychology and have just built up a bizarre straw man of what it supposedly is.

Science, of which psychology is a part, like philosophy, seeks to understand the world. In fact, science is a branch of philosophy. As we find out more, this does demystify the world. But is that a bad thing? Would you prefer to live now, or in the Dark Ages in ignorance? Perhaps we can wistfully wish we were poets postulating upon unknowns in a romantic era. But, in reality, I would take being able to do the things I can do today, including understanding my own psychological foibles so that I can better understand myself in order to cope and flourish in the world of today. And it doesn’t stop me writing poetry.

And this is precisely what Kahneman’s work seeks to do. Understanding why we make irrational decisions, understanding our intuition, is hugely important and has very pragmatic applications (as the recent BBC documentary, Horizon, on his work quite explicitly showed). Whether it be financial decisions by stockbrokers and bankers that brought down the world’s economy, individual financial decisions going awry due to loss aversion, or running policemen not being able to witness other policemen beating up a suspect and ending up going to jail as a result (see here), there are real applications to psychology that affect us all. Understanding them is the job of psychologists and is very bloody useful.

Finally, let me remind you of what Guy said with regard to personhood (where “it” is personhood):

The fact that we can’t do this doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist (or has ontic reality as you say). Indeed, in our interactions with each other, in our very pretension to make utterances that signify and have value, we cannot help but assume that it does exist. The problem is that it pre-exists our discussion of whether it exists. Unless it did we couldn’t begin to discuss anything. There’s the rub! There’s the glory and mystery of the human condition. We have to accept and assume something we can’t prove. Otherwise we can’t even get off the ground and interact as people. Something of a wondrous paradox which won’t submit to the exigencies of explanation. Perhaps this says something about the status of human reason. Irritating isn’t it?

What Guy does wrong here is conflate personhood with consciousness, which is the fallacy of equivocation. He is sort of thinking of Descartes cogito ergo sum here, by the looks of it. That paragraph is simply wrong, incoherent. We don’t have to presuppose personhood at all. In fact, no one can really agree what it is, let alone accept it as objective fact. Personhood is a group of properties which we may or may not agree define us as being human beings.

Daniel Dennett, originally in “Conditions of Personhood,” Richard Rorty, ed., The Identities of Persons (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), claimed personhood is defined by

A is a person only if:

i. A is a rational being.

ii. A is a being to which states of consciousness can be attributed.

iii. Others regard or can regard A as a being to which states of consciousness can be attributed.

iv. A is capable of regarding others as beings to which states of consciousness can be attributed.

v. A is capable of verbal communication.

vi. A is self-conscious; that is, A is capable of regarding him/her/itself as a subject of states of consciousness.

So this is his definition which we may or may not agree with. But this does not mean that personhood as a concept or a thing is ontic or objective. This is a concept bringing together many other concepts which we understand in a conceptualist context. Psychology is connected in some ways to these ideas since it is the understanding of how the human psyche works in a physiological, neural and conscious way. To say psychology is not useful or true or should be ignored (yes, truth needs to be defined here) is problematic. I do deny the continuous “I” as being ontic for many reasons, but the “I” is useful, perhaps pragmatically necessary, to get through life as we know it. Contracts would be invalidated with my ‘correct’ understanding of the world. The continuous “I” is very useful if not entirely real in an objective sense.

Fascinating as this subject is, as realism vs nominalism/conceptualism really is, I don’t think it is a useful diversion for critiquing psychology, or just flatly refusing to deal with it or the people who research it.

Really, what I think this comes down to, and knowing Guy and his previous discussions, is naturalism. I think he is projecting his supernaturalist worldview on to the idea that psychology is supposed to be a science, that science isn’t everything, and thus psychology is somewhat doomed from the off. This seems to be supported by his blogpost:

Faced with the glorious, not to say marvelous fact of a human being, Daniel Kahneman and the psychologists don a lab coat, pick up a clip board and conclude merely that humans are less than the computers they have given existence to. They achieve this by dressing up some subtle and, essentially, mathematical problems which computers can solve (eg the Linda problem, the sunk costs fallacy etc) in simple-seeming clothing and then being delighted when humans fail to solve them correctly. This, they say, is because of their dependence on heuristics and their lack of awareness of their cognitive biases.

This idea that humans are victim to cause and effect is indeed a prerequisite of psychology. In fact, psychology struggles to make sense of free will. You wouldn’t sit down with a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist and explain a problem for them to just retort, “Well, it looks like you just chose to do that, so I can’t really help you!” This is meaningless and not a fair reflection of the state of affairs. Things happen for a reason. Things in our brains and thus in our conciousnesses. But Guy doesn’t like this idea of cause and effect, it demystifies his opinion of what humanity is and should be. Unfortunately, that doesn’t bear up to empirical scrutiny, whether he likes it or not. He continues on his blog:

In fact, the reason why many humans get Kahneman’s problems wrong are manifold:

1) We are not mainframe computers with large computational competence for making simply mathematical calculations. We are much more than that. We invented the mainframes to avoid the tedious.

2) We are duped by the way in which the questions are framed by the psychologists. Some of their colleagues have actually pointed this out.

3) We are endowed, in a way which computers are not, with the amazing capacity for self-awareness. This gives us an understanding of context. When faced by one of Kahneman’s problems we make swift judgements that they can’t be worked out quickly or are too trite and pedestrian to waste our valuable computational resources on during the short time we are on this planet.

Without seeming to realise that point 3 is precisely what Kahneman has spent 45 years deciphering and understanding with a great deal of success. Guy, as a self-professed humanities man, is very concerned that science and ‘scientism’ are trampling on the humanities, to the point that he swears by Leon Weiseltier against Steven Pinker in their debate over science and the humanities.

This idea that science is somehow attempting to destroy the artistic beauty of poetry or something is really not a valid reason to refuse to acknowledge the work of every brilliant research psychologist in the world, now. Building up fences (between science and the humanities) is arbitrary, accepting that there are blurred lines possibly more accurate. The fact that Shakespeare can include so many wonderful pieces of psychoanalysis which are backed by modern empirical understanding is great. The fact that Cambridge University runs a course on Shakespeare and Psychology is nothing short of delicious in its irony.