Gentrification benefits “urban pioneers,” but what about those who are native urbanites? Yes, clean streets, cafes, shops, art studios, and shorter commutes to work in the city are very nice to contemporary Lewis and Clark pioneers. However, for all the fresh faces and new wealth, we lose out all too often on the cultural riches of the displaced, vibrant traditional communities. Such cultural loss is an unintended consequence.

Many who are forced to abandon their long-standing communities and migrate from the urban center are poor, and thus are unable to bear the costs of the “upgrades.” As in past forced migrations, often these poorer people are ethnic minorities. In the past, many of them—African Americans—sang the Blues; they improvised their existence with Jazz. Just think how impoverished America would be without these art forms. Just think how enriched we would be if we were to work to foster return migration for people like them who are being displaced today.

Gentrification as “revitalization”—and the accompanying term of “urban pioneer”—can convey a poverty of language and culture. When we refer to a neighborhood as revitalized, we may think there was nothing previously there of any worth, except perhaps antique homes that needed a facelift. In America’s past, pioneers often eradicated cultures deemed primitive and expendable along the trails they blazed. For all the pioneers’ merits such as ingenuity and industry, we struggle with resourcefulness and redistribution. As Sitting Bull once said, “The white man knows how to make everything, but he does not know how to distribute it.” While we are often rich in financial capital, we are often poor in social capital.

In addition to the loss of cultural riches, what are some of the other “unintended” consequences of gentrification?

How about gang violence? One researcher, Christian Smith, focusing on Chicago in the 1990s and early 2000s, claimed, “while individuals and investors reduce homicide rates through gentrification, when local authorities demolish public housing, they may actually be intensifying gang violence through forced relocation.” See her article “Gentrification may not be a silver bullet to prevent gang violence, and in some cases, it may even make it worse” published at the London School of Economics’ US Centre. All too often, we blame the victim in addressing the problems. While we should never excuse violence and theft, we must also see that gang violence is not simply this or that group’s problem; it is everyone’s problem. Community upheaval intensifies problems; gentrification may actually foster gang violence at times.

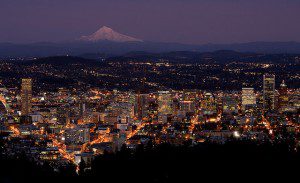

How about mental illness? Can it be an unintended consequence of gentrification? An article titled “Forced migration and mental health: prolonged internal displacement, return migration and resilience” in Oxford’s journal International Health maintains that those experiencing long-term displacement in their own country are at great risk of developing mental disorders, further taxing the health of the global community. While individual and collective resilience can serve as deterrents, we need to develop widespread strategies involving every sector of the society to increase resilience through solidarity. Faith communities are key to such strategies, as religious institutions like synagogues and churches have often been centers of vitality for marginalized communities. Thus, it is quite disturbing when churches—including those in cities like Portland—further foster unintended upheaval through gentrification by narrowly targeting and catering to urban pioneers rather than working together with historic ethnic faith communities to retain the traditional communities. Certainly, there is a need to reach out to the new urbanites, as long as these church plants work to strengthen the fabric of their neighborhoods by bringing the diverse groups together with native churches to build the beloved community (Refer to my article, “The Gentrified Church—Paved with Good Intentions?”).

How about diseased souls? Can spiritual sickness be an unintended consequence of gentrification? When one part of the body of Christ grieves, the whole grieves (1 Corinthians 12:26)—whether consciously or not. Sickness impacts the whole body, whether physically or spiritually. Biblically speaking, there is only truly one church in any given city—the church in Corinth, Colossae, and Rome, for example. The same holds true for places like Portland, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, and New York. Thus, we who are Christian leaders must work together in our neighborhoods. We need to work together to retain vulnerable communities, and return them to our neighborhoods when they are displaced. If displaced to other regions—often suburbs, churches in these contexts must work together to help foster resilience in the diaspora.

Churches can also add their voice to others in their communities who call for creating more inclusive cities. According to an article on gentrification in The Atlantic CityLab,

Gentrification and displacement, then, are symptoms of the scarcity of quality urbanism. The driving force behind both is the far larger process of spiky reurbanization—itself propelled by large-scale public and private investment in everything from transit, schools, and parks to private research institutions and housing redevelopment. All of which points to the biggest, most crucial task ahead: creating more inclusive cities and neighborhoods that can meet the needs of all urbanites.

The faith community must add its collective voice to the call for change. The necessary resilience to safeguard and nurture diverse communities that enrich people of all ethnic backgrounds and across the economic scale requires every sector—religious, economic, political and beyond. It requires a change of attitude toward the dispossessed, a change in our understanding of what “adequate” and “affordable” housing entails, and a change from passivity to activity by providing protective measures to ensure stability for those most vulnerable to displacement.

An article on LA gentrification in the Los Angeles Times gets at all these issues:

People living on the streets and in the single-room-occupancy hotels of downtown L.A. have enough to cope with already without being hosed out of the way for iPod-wearing, latte-drinking professionals strolling to work in Bunker Hill. If urgently needed change in downtown L.A. is to improve life at all for those who live there now, some provision must be made for adequate, affordable housing.

Caps on loft conversions, greater rent protections for tenants and subsidies for people unable to afford rental housing would also help ensure that poverty is not simply moved elsewhere.

If the debate about skid row is to be productive, we need to reject the characterizations of its dwellers as unfortunate failures and instead evaluate the ways in which a booming housing market can do damage — economic, social and psychological — to those who live in poor, underserved neighborhoods.

A lot of intentionality goes into urban planning. It is hoped that such intentionality will become more expansive and involve all stakeholders, not simply the most powerful shareholders of this or that corporation, city council, or church board. Intended as well as unintended consequences follow from gentrification. We cannot excuse those that are unintended consequences as benign. After all, ignorance is never really bliss. It is a cancer that ravages individuals, displaced communities, and the society as a whole.

For a robust discussion on these themes, please join The Institute for the Theology of Culture for “Urban Planning: Unintended Consequences” at Life Change Church in North Portland, Wednesday April 27th from 7:00-8:30 PM.