The Dunning-Kruger effect is a term for people who are too ignorant to recognize that they are mistaken. If you work in politics or public health, it’s easy to feel as though these people are everywhere, but it is possible for most of us to spot people or systems which are better at making certain judgements than we are. And if we find one, it’s rational to defer to its decisions.

This is essentially the kind of system G.K. Chesterton claimed Catholicism to be when he declared it to be a ‘truth-telling thing.’ He was claiming to have found a system that was so much more reliable than his own judgement that he felt it prudent to defer to the wisdom of the church not only when he was undecided, but even if his moral intuitions were in stark opposition to church teaching.

This sounds like a textbook case of organized religion asking believers to doff their brains as well as their hats when they stand before the altar, but I don’t find Chesterton’s position to be irrational in theory. When I read books on quantum theory written for laypeople, I usually have to try to reform my expectations and ideas. This isn’t because quantum theory is irrational, it’s because my intuitions and common sense are wrong. My normal modes of thought are a good-enough approximation of the world for day-to-day life, but they’re no more accurate than Ptolemy’s epicycles.

When Eliezer Yudkowsky talks about rationally deferring to the judgement of another, he uses the example of a computer programmer who is not very good at chess but is able to design a piece of software that plays very well. The programmer still doesn’t know how to play high level chess. He built a system that produces correct results in a way that he can’t replicate in his own mind. If he wants to win matches, he ought always defer to the computer’s suggestion.

It’s a lot easier for the programmer to feel confident that the software is a better chess player than he. It’s harder to figure out what kind of evidence could justifiably give Chesterton that kind of confidence in the church’s moral judgments.

It’s hard to look at any particular move the chess computer makes and judge whether or not it’s a good move, but we don’t have to evaluate the process. We can just look at how many wins the program racks up against different levels of opponents. It’s even easier if we’re trying to build programs to categorize data (as I am in my machine learning class). Every time the algorithm is tweaked, we check it for accuracy.

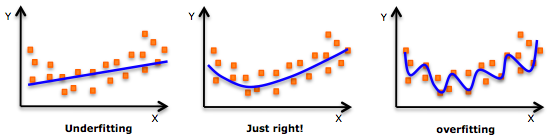

But if you try to apply this kind of test to a moral truth-telling thing, you run into two big problems. First: there’s the problem of overfitting. In computer science, it’s bad practice to train your prediction program on all the data you have. It’s easy to assume that more data must be better, but using everything you’ve got is going to make your program really good at categorizing the data you already have and really bad at predicting anything that wasn’t in your original data set. After all, the most accurate program is one that just stores all the data you gave it in a big lookup table and returns the numbers you inputted. Not a big improvement. In computer science, you avoid this problem by withholding a certain subset of the data from the computer when it’s learning. When it’s generated a model, you test that formula for accuracy by applying it to the datapoints you held in reserve.

You can’t pull this off with moral quandaries. A church or a philosophy isn’t isolated from the world, so you can’t hold some conundrums back and then try to use them as test cases for the first principles the group you’re evaluating has on offer. So, instead you’re left suspicious that any teaching, especially one sourced from a long, complicated book might have more to do with having an intuition about an answer and hunting up something in your canon that supports it. That hardly likely to give you the confidence to throw over your intuitions for the dogma of a new teacher.

That’s a technical issue, but there’s an ever bigger stumbling block for an aspiring pupil. Unlike the chess example, where it’s easy to keep score by number of wins, it’s hard to figure out how you judge one moral system as more accurate than another.

I’m not preaching relativism, some moral systems take themselves out of the race. There are enough commonly-held moral intuitions which I assign a high level of confidence that I feel comfortable disqualifying any system that doesn’t preach them. To name a few names: solepcism, objectivism, and dark kantianism. But if I consider only those systems that can coexist with my list of unshakeable moral precepts, I haven’t found a useful moral system, I’ve just found the ethical equivalent of a generative set — a summary of my list. To put it formally, I’ve come up with a set of first principles/axioms that I know I can derive some true theorems from, but I have no idea whether this set of axioms only generates true theorems. When two systems that clear my initial bar diverge, I don’t have a good way to pick the winner.

The best schema I have is to look for systems that usually turn out to be right even when I think they’re wrong. That’s the kind of evidence that Chesterton and more modern-day converts like Jennifer Fulwiler of Conversion Diary claim to have found. That’s not been my experience of Catholicism, and most of the predictions it offers me are stuck behind the firewall of faith, impossible to test until you’ve assented at least to the point of theism.